The Rocky Mountaineer concept was created by Harry Holmes, a railroad engineer, and Pat Crowley, a tourism entrepreneur, both of Jasper, Alberta. Together they developed a business plan which they presented to Via Rail prior to Expo 86. It was designed as an all-sightseeing train pulled by retired Canadian National 4-8-2 6060 in the Canadian Rockies. Originally, it began as a once-weekly Via Rail Canada daytime service between Vancouver, Calgary and Jasper. The first departure was on May 22, 1988, with a special train for the travel industry. Soon, another one was made for the traveling public on June 9, 1988, called the Canadian Rockies by Daylight. To maximize scenic views, this service operated only during the day, with an overnight stop in Kamloops. These were express services, with no intermediate stops.

On June 4, 1989, Via began its second season of the service, renaming the service the Rocky Mountaineer. The final summer Rocky Mountaineer (under Via Rail branding) departed Calgary and Jasper was on October 12, 1989 and arrived in Vancouver on the 13th. Rocky Mountaineer was removed from schedules and marketing in May 1990. After two financially unsuccessful seasons, there was to be a change in approach. The Federal Government decided to see if the private sector could do a better job. The then Minister of Transport and Minister of Finance Michael Wilson decided to sell off the route, equipment, branding and book of business in the fall of 1989. In early November, advertisements were taken out in a number of newspapers soliciting interest in the Rocky Mountaineer.

The federal government curtailed the subsidies to Via Rail in 1989, dramatically reducing services (especially the transcontinental service). Rocky Mountaineer was a tourist service, and as such the government felt the funds could be better spent on other bigger priorities. They asked (at the time) Via Rail and CN Rail CEO Ron Lawless to organize the sale of the route, equipment and book of business to the private sector. The marketing of the Rocky Mountaineer sale started November 12, 1989 and sale processes were run by recently retired CN Executive Charles Armstrong. Submissions of interest demonstrating financial and operational capabilities were required by January 15, 1990.

Initially, there were 20 interested parties but after phase one of the bidding process, that group was reduced to three parties left to make a decision. One bidder was Westours Holland America, subsidiary of Carnival Cruise Line. The other two were a group of Via Rail executives and a Western Canadian entrepreneur. In March 1990, following the bidding process, the route's equipment, book of business, 12 coaches, two baggage cars, along with various equipment and branding, were sold to Vancouver businessman Peter R.B. Armstrong's Armstrong Hospitality Group Ltd. The inaugural train journey took place on May 27, 1990.

In 1995, the company launched its GoldLeaf Service, featuring bi-level rail cars with dome windows and stunning panoramic views on the upper level, and large windows in the lower-level dining area where meals are freshly prepared from a selection of regionally inspired dishes. In 1999, Rocky Mountaineer set the record for longest passenger train in Canadian history at 41 cars.

Rocky Mountaineer trains only operate in the tourist season of April to October. They operate exclusively during the day and sleeper services are not offered. All trips include overnight stops at which passengers disembark and stay in hotels.

My Journey

My day started pre-dawn as I checked out of the Day's Inn and rode Skytrain to Pacific Central Station, where I checked in with the Rocky Mountaineer Staff and received my car/seat assignment. I went for MacDonald's in the station for breakfast before doing a few word fill-in puzzles until boarding time. With a toot of a train whistle, I led the way to the train and was the first passenger of the 2001 season to board, climbing onto car seven of a twenty-two car consist. Although it started to rain, nothing was going to damper my enthusiasm at the start of this rail journey. My car attendant, Tina, handed out letters to all passengers which, when held up in order, read "Cheers! To a great 12th Season". I held up the "S" and the exclamation point. As we departed Vancouver, we gave all the employees a big send-off with the letters and waving. The entire office staff of Rocky Mountaineer were on the ground to see us off and I wondered if we won the contest that the onboard crews were having? I hoped so.

Rocky Mountaineer Railtours GP40-2LW 8013, ex. Alstom 9621, nee Canadian National 9621, built by Electro-Motive Division in 1975, was the sole power for our train. Our route out of the city was the same as VIA Rail's Canadian, although the large big difference, and selling point, is the all-daylight operation which enables passengers to see all the scenery.

Pulling out of a rainy Vancouver.

Skytrain meets the BNSF and our Rocky Mountaineer at New Westminster. Add to that the fantastic cars and great service the crew provides and you have a winning combination. Breakfast was served at your seat upon departure, but as I am a very finicky eater, I was off to the vestibule for some pictures in the pouring rain.

Crossing the Fraser River at New Westminster and to Mission City.

I then sat back enjoying the passage through Canadian National's yard and out along the Fraser River to Page then further east, we crossed the Fraser River again at Mission City to reach the Canadian Pacific's main line.

Curving onto the main line. All eastbound trains travel on Canadian Pacific tracks east to Basque, while westbound trains travel on Canadian National; this is termed directional running and started in 1995. For me, this was now where the fun was going to start, a daylight ride up the Fraser River Canyon in the rain. I did not care what the weather was like, I was going to enjoy this no matter what. We passed Nicomen Island before crossing the drawbridge at Harrison Mills.

Harrison Mills, situated on a floodplain at the western foot of Mount Woodside, at the outlet of Harrison Bay. This bay is a large, lake-like backwater of the Harrison River, located just before the river's confluence with the Fraser. The unique geographical location of Harrison Mills offers visitors a chance to immerse themselves in the natural beauty of British Columbia, making it a perfect destination for outdoor enthusiasts.

A westbound Canadian Pacific Railway train across the Fraser River on Canadian National's tracks. We popped out of the Twin Tunnels and passed through Agassiz as the rain eased off and the clouds hung low at this point, obscuring the mountain peaks.

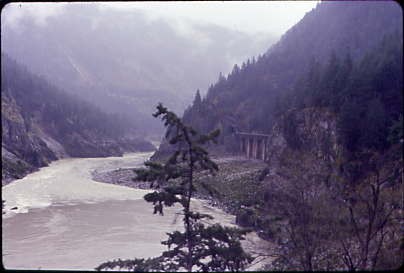

The lower Fraser River Canyon.

Looking across the Fraser River.

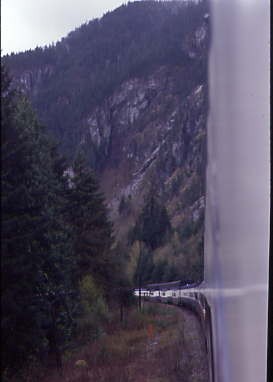

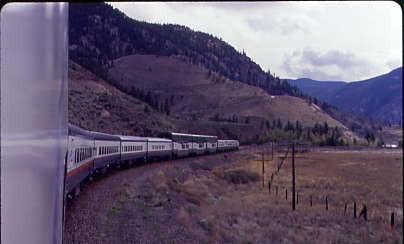

The view along our train.

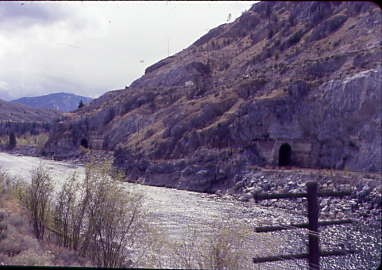

Exiting a tunnel.

A rear-facing scene.

Rocky hillsides.

We travelled deeper into the Fraser River Canyon as the rain stopped and passed through Ruby Creek and on the other side of the river was the District of Hope.

The scene towards the front of our train.

Crossing one of the many creeks entering the Fraser River.

Looking back at that last bridge we crossed.

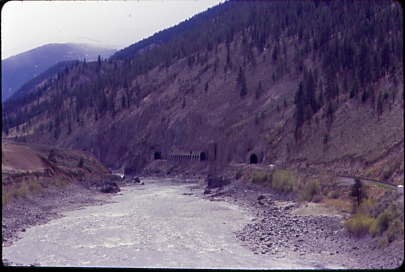

Looking across the river at a tunnel on the CN line.

The interior of my coach for this fantastic trip. We bridged American Creek and travelled through Choate where the canyon narrows and deepens as we crossed Emory Creek prior to rolling through Yale.

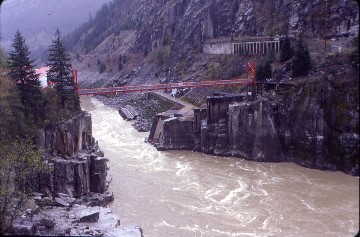

The view towards Hells Gate. This is a narrow rocky gorge of the Fraser River Canyon south of Boston Bar. Explorer Simon Fraser recorded a difficult portage in 1808 around the churning waters of this section of the Fraser River. First known as the "great canyon," its name is associated with the disastrous impact of Canadian Northern Railway construction on the river's salmon resources. In 1913, what became the Canadian National Railway hewed its way through the Rockies and the treacherous Fraser Canyon. While blasting for the passage of the railway, a rock slide was triggered which partially blocked the Fraser River at Hells Gate. A dramatic drop in the salmon run resulted.

Thirty years of work by dedicated scientists and several years' construction were required to repair man's damage. Today Hell's Gate fishways, built by a joint Canadian-United States Commission and completed in 1966, stand as monument to man’s dedication and ingenuity. In 1917 the International Pacific Fisheries Commission was formed by Canada and the United States. Since that time, efforts have been made to improve the run of salmon to the spawning beds. This was brought about by the construction of fishways, which help the salmon through the difficult sections of the Fraser River System. Fishways are now at Yale, Hells Gate and Bridge River Rapids. The Hell's Gate Fishways were opened in 1945 and their effect on migrating salmon can be shown throughout the experience at the Quesnel Lake System. In 1941, only 1,100 fish reached the spawning beds, by 1973, the number had increased to over 250,000 fish, and in 1981, this number had increased again to over 800,000 These increased numbers mean to the fishermen a catch of several million fish. The survival rate of young salmon has been improved through the construction of artificial spawning channels. These serve the sockeye population, while a further channel at Seton Creek has been built for pinks. The Weaver Creek Channel, completed in 1965, produced, in its first five years of operation, a total catch to fishermen of over 600,000. The Fisheries Commission hopes, over time, to restore the Fraser River to its pre-1913 status as a salmon stream.

Here, the Hells Gate Airtram delivers visitors from the Trans Canada Highway to the bottom of the canyon. This airtram was built by Habegger Engineering Works of Thun, Switzerland and one of their mechanics came over to help set up the system. Fiber rope was shot across the canyon with a crossbow from the lower terminal to the upper cliff edge (half way) and then from the cliff to the upper terminal. Once the rope was in place, a small cable was attached and winched to the upper terminal, and then the 44 mm wide steel track rope. It took many hours to get this 1,000 feet of track rope in place as it was not allowed to touch any other metal or the ground.

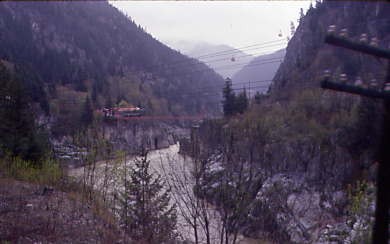

We passed through Hells Gate with almost everyone taking pictures or video and is a very impressive landmark. Continuing north, we passed through the last of the tunnels before China Bar and crossed Scuzzy Creek before arriving at North Bend for a crew change.

Canadian Pacific 9620 East.

Canadian National 2616 East. It is here where the canyon started to narrow and plunged into another tunnel. The Fraser River was a muddy brown as it churned and descended its way to the Pacific Ocean. A Canadian Pacific Railway coal train was running across the river on the Canadian National line, just one example of the directional running that the two railways employ with westbound trains running on Canadian National and the eastbounds on the Canadian Pacific between Mission City/Page and Basque. I filled out an order form for trip souvenirs which would be waiting for me tomorrow morning, then we traversed Skow Wash and Kwoiek Creek before passing through Kanaka Bar. We entered Keefers Tunnel and went right out onto Canadian Pacific's Cisco bridge crossing of the Fraser River.

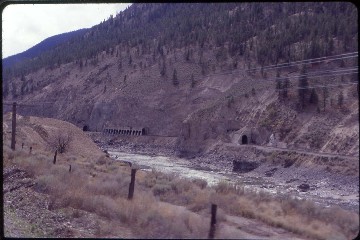

Rolling through the canyon along the slide detector fences.

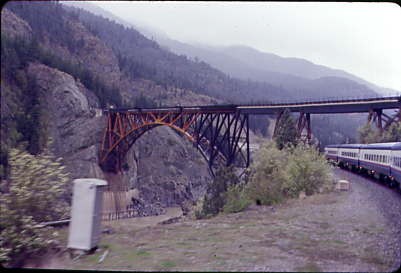

The Cisco Bridges, where both the CP and CN changes sides of the Fraser River Canyon. The Canadian Pacific version is a three-span, 520 foot truss bridge with two short Pratt truss spans at each end of the longer Parker truss main span. The south end of the bridge enters directly into the Cantilever Bar Tunnel and the original span, built by Joseph Tomlinson, was pre-fabricated in England and shipped to Canada in 1883. The bridge, then one of the longest cantilever spans in North America, was then constructed by the San Francisco Bridge Company. When the current bridge was built at Cisco in 1910, the original span was moved to the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway on Vancouver Island to cross the Niagara Creek Canyon.

Our train then went under Canadian National's bridge, a truss arch bridge, 810 feet long and 220 feet high with its northwest abutting into a near-vertical rock face. The southeast end of the bridge crosses the CPR tracks about 330 feet north of the CPR bridge. In other words, the railroads switched sides of the canyon. This was necessary because the Canadian Pacific built through the canyon first and took the easier route, with the Canadian Northern building through here on the other side of the canyon. Canadian National did have the advantage of more modern construction methods. Cisco was a truly spectacular place.

The Canadian National crosses the Fraser River at the junction of the Thompson River and we would now follow the river into the Thompson River Canyon.

We followed the east side of the Fraser River for about eight more miles to Lytton, where we diverted from the muddy Fraser River and started to follow the deep blue Thompson River to Kamloops.

The Thompson River Canyon.

Interesting rock strata here.

The Painted Canyon section of the Thompson River Canyon.

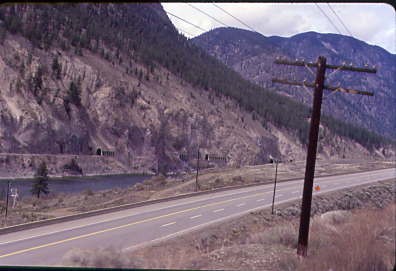

Multiple tunnels on the Canadian National line, built canyon years after the Canadian Pacific line.

The Thompson River Canyon was really beautiful.

Curving through the canyon.

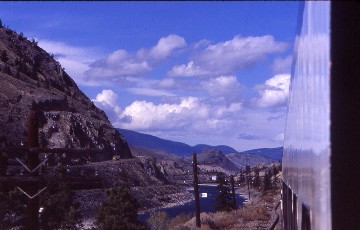

Views ahead and to the rear of our train; below is Trans Canada Highway 1.

The views kept improving.

I love the colour of the Thompson River.

Towards the front of our train. The first area of this canyon that we entered is known either as Painted Canyon or Rainbow Canyon for the vivid colours in the rocks. The Canadian Pacific line was built on the south side on a ledge above the river and has the easier route, while the Canadian National line plunges through eight tunnels and rock sheds to achieve their route through the canyon. It was truly spectacular and I was happy knowing that I would be riding on the Canadian National route through here in daylight in three days.

I was really enjoying the automatic winding feature on the camera I bought during my visit to Canada last December since it was coming in very handy as we made our way through the lower Thompson River Canyon prior to our passing through the community of Thompson. The countryside was becoming more arid as we proceeded east.

Incredible!

Rounding another curve.

Tunnels on the Canadian National line.

A view up the Thompson River Canyon.

Another curve, another view.

Skoonka Tunnels on the Canadian National line.

The view ahead!

We snaked through the canyon.

Murray Creek Waterfall dropped into the Thompson River Canyon.

The canyon walls were becoming interesting.

A westbound Canadian National train rolling on their railway.

Our train looked excellent.

Looking back with the Jasper section bringing up the train's markers.

More tunnels on the Canadian National, which I would be travelling through back to Vancouver.

The Canadian National tunnels continue.

A beautiful train on a beautiful day.

Love the blue in the Thompson River.

Rolling east on a fantastic afternoon.

A look back with hoodoos above the train. These are tall skinny spires of rock that protrude from the bottom of arid basins and "broken" lands. Hoodoos are most commonly found in the High Plateaus region of the Colorado Plateau and in the Badlands regions of the Northern Great Plains. Ranging from 4.9 to 147.6 feet, they typically consist of relatively soft rock topped by harder, less easily eroded stone that protects each column from the elements. They generally form within sedimentary rock and volcanic rock formations. Hoodoos are found mainly in the desert in dry, hot areas. In common usage, the difference between hoodoos and pinnacles (or spires) is that hoodoos have a variable thickness often described as having a "totem pole-shaped body". A spire, on the other hand, has a smoother profile or uniform thickness that tapers from the ground upward.

Hoodoos range in size from the height of an average human to heights exceeding a 10-story building. Hoodoo shapes are affected by the erosional patterns of alternating hard and softer rock layers. Minerals deposited within different rock types cause hoodoos to have different colors throughout their height.

We crossed Pukaist Creek then Canadian National 2532 West made us wait to enter their main line again at Basque.

Entering Basque, where the driving of the last spike of the Canadian Northern occurred on January 23, 1915.

Switching railroads at CP Rail Basque where we left the Canadian Pacific.

Our train entering the Canadian National main line at CN Coho.

With the Canadian Pacific main line above us, we continued east along the Thompson River.

About to enter the Black Canyon of the Thompson River and passed through two more tunnels.

Having left Black Canyon, we continued along the Thompson River with the Canadian Pacific main line across the water.

The Rocky Mountaineer about to enter a tunnel, one of five tunnels in this canyon and along with the rock sheds, it was very impressive. We went next through the community of Spences Bridge before travelling over the Nicola River.

The wind blowing the dust off the canyon walls.

Crossing the Thompson River once more.

Blue water and white clouds made for a fantastic scene.

Another crossing of the Thompson River.

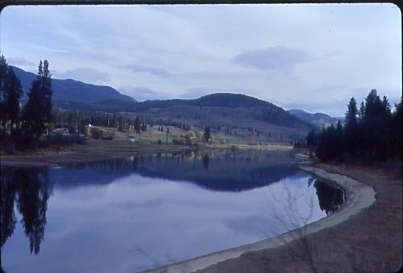

Kamloops Lake.

The Canadian National ran along the north shore and Canadian Pacific ran along the south shore of Kamloops Lake.

Kamloops Lake as we approached that city, our overnight stop.

Here the route turned eastward to Kamloops. The weather had cleared so Lookout Point and White Mountain could be seen.

After that it was over Cornwall Creek to the Village of Ashcroft then we crossed the Thompson River several more times before the community of Savona, where we traversed the river twice more just short of Kamloops Lake, which we followed the rest of the way to Kamloops.

Along the shores we passed through a few more tunnels and bridged both Carabine Creek and the Tranquille River before the smokestacks on the outskirts of Kamloops came into view. We crossed the North Thompson River and turned onto a Canadian National Railway branch line (some new mileage) passing St. Joseph's Church, which served as the model for the one in the film "Unforgiven", before crossing the South Thompson River and stopping at the Canadian National station in Kamloops.

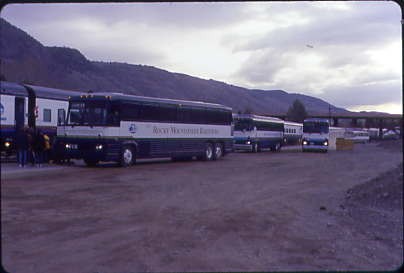

Kamloops 4/17/2001

The Rocky Mountaineer had a fleet of buses to take the passengers to their hotel rooms for the night which was part of the tour package. I stayed at the Aberdeen Inn in the new part of the city out in the hills to the south then walked to Walmart to buy a sweatshirt so I would be warm tomorrow as I rode through the mountains in the vestibule. I had bought a ticket on the train to the Two Rivers Junction Dinner Theater, so the bus returned to the hotel and picked up those who were attending the event which was near where the train was parked.

I was the first person to be seated for their 2001 season and the meal was an all-you-could-eat buffet and I did just that. The show was the story of Billy Miner, whose real name was Ezra Allen Miner, an outlaw (born circa 1847 in Bowling Green, Kentucky who died on September 2nd, 1913 in Covington, Georgia. He was reputed to be the first train robber in Canada, although bandits had robbed a train of the Great Western Railway in Ontario on 13 November 1874, 30 years before Miner arrived in Canada. Miner was the first to rob the Canadian Pacific Railway and thus became an outlaw hero in Canadian folklore. Miner was known as "The Grey Fox" and the "Gentleman Bandit" because of his polite manners during holdups. Miner was also credited with being the outlaw who coined the phrase "Hands up!" I enjoyed the show so much that I bought the CD. After the show, the bus took us back to the hotel where I had a good night's sleep.

Rocky Mountaineer 4/18/2001

The night passed all too quickly and I was up and ready for a full day of train-riding on a new route that I had never ridden, which included that portion which I had seen when I was young during family vacations at Golden when both the eastbound and westbound Canadians passed the campground at the bottom of Kicking Horse River Canyon. This classic General Motors bus transported the passengers back to the train.

I walked down to the front of the train before boarding the Calgary section which now had two locomotives.

Canadian National stock car 800042, exx. Canadian National 172473, exxx. Canadian National 344700-346699 series box car, nee Grand Trunk Railways 24500-246499 series box car built circa 1913 and Canadian National wooden caboose 76058, exx. Intercolonial Railways 87787 1923, nee Canadian Government Railways 8778 built circa 1900. Both these were previously displayed at the Travel Infocentre at Halston Esso on Kamloops Indian Reservation.

Leaving town, the Rocky Mountaineer moved slowly down the rest of the Canadian National branchline to enter the Canadian Pacific main line.

We followed the South Thompson River east along the Campbell Bluffs with those hoodoos.

Interesting scene of the Campbell Bluff in the South Thompson River Valley.

A beautiful scene along the South Thompson River.

A look back to the northwest as we continued our journey.

Another view in the South Thompson River Valley.

Past Campbell Creek, we passed the Billy Miner Train Robbery site where he robbed the wrong train and came away with just fifteen dollars. After the train crossed Monte Creek, we passed south of Lion's Head; Rocky Point Bluff was on the south side and further along, Whisker Hill was on the north side near Pritchard. We ran through Chase and a little later travelled above Little Shuswap and Shuswap Lakes.

At Notch Hill, the line split, with a much longer and easier grade for westbound trains.

Our train climbing Notch Hill.

As we ascended, a view looking back north at Shuswap Lake.

Notch Hill.

Shuswap Lake.

Our train running along the shore of Shuswap Lake. We ran through Carlin and near Tappen, reached the shore of the Salmon Arm of Shuswap Lake which we followed for over fifteen miles to the south end of the lake and the city of Salmon Arm. We turned north along the lake for a few miles before turning right through a pair of tunnels which took us to the east end of the lake at Sicamous, where we crossed Sicamous Narrows, leading to Mara Lake. Sicamous is the house boat capital of Canada. From here we started our climb over the Monashee Mountains along the Eagle River and I met Natalia, a car attendant, who was a very likeable person and we learnt that we had several things in common.

Craigellachie, where the Revelstoke Railway Museum has a satellite location commemorating the driving of the last spike on the Canadian Pacific Railway on November 7, 1885. There is also a cairn and Canadian Pacific caboose 437336 1992, exx. Canadian Pacific 439512 1979, nee Canadian Pacific 437336 built by the railway in 1949.

We met Canadian Pacific 5234 West at Taft on the climb to the divide at Clanwilliam that separates the Eagle River drainage from the Columbia River drainage.

The Enchanted Forest Amusement Park. We ran along Griffin and Three Valley Lakes and passed through snowsheds and tunnels.

Three Valley Lake.

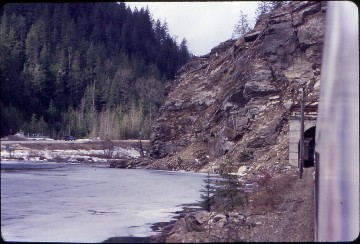

Passing the iced-over Tumtum Lake.

From the summit at Clanwilliam, we followed Tonkawalta Creek along with another westbound grade separation down to the Columbia River, which we crossed prior to stopping in Revelstoke to change crews.

Revelstoke also has a railway museum near the station.

Our train crossed the Columbia River just west of Revelstoke.

The Canadian Pacific parade train.

We climbed following the Illecillewaet River.

Starting the climb up Rogers Pass. We crossed Greeley and Twin Butte Creeks before passing through a tunnel at Milepost 106.3.

I really enjoyed the vestibule.

Our train ascending Rogers Pass. Canadian politicians did not mince words when they learned in 1871 that Sir John A. Macdonald, the country's first Prime Minister, had pledged to build the longest railway in the world within ten years. Opposition leader Alexander Mackenzie called the promise "an act of insane recklessness..." The Prime Minister's trans-continental railway dream was intended to lure the colony of British Columbia into the new confederation of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, Ontario and Manitoba. A decade of fierce political battles and brutally difficult exploration followed the announcement, in the campaign to select a route that would connect Pacific tidewater to the rest of Canada. Surveyors explored more than a dozen passes during the "Battle of the Routes", with crews confronting biting flies, heat, muskeg and bone-chilling temperatures in winter. Forest fires and fast-flowing rivers took many lives.

In the absence of any roads, supply lines were a major undertaking. Despite all of the hardships, 46,000 miles of reconnaissance surveys were conducted - all of them on foot and horseback. The surveyors finally recommended the Yellowhead route as the best choice after ten years of scouting, and the federal government signed a contract with the Canadian Pacific Railway Company to build the rail line over Yellowhead Pass. A year later, the railway company made an about-face - choosing to tackle an entirely different southern route through Kicking Horse Pass in the Rockies and over the Selkirk Mountains. The general manager of the railway, William Cornelius Van Horne believed in calculated risks. He had made a choice about the Selkirk Mountains before he was sure a pass even existed. He had decided that a more direct route to the Pacific was required to reduce the costs of construction and operation.

It had now become urgent that the railway company find a pass through the seemingly impenetrable peaks of the Selkirks. The westbound construction crews were already racing across Manitoba towards the distant Rockies. The eastbound company was working its way up the Fraser River valley. The Canadian Pacific Railway's fortunes now lay with Major Albert Bowman Rogers, a Massachusetts-born railway surveyor. Rogers earned an engineering degree at Brown University and became an instructor at Yale. He was known as "Major" for having fought in the Sioux Rebellion of 1861; "Railway Pathfinder" for his work on the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad; and "Hell's Bells Rogers" for his penchant for profanity. Rogers was quick-tempered and experienced only in prairie surveying. Disliked by other engineers, and by his workers (whom he fed poorly and continually insulted), he was also honest, hard working, and frugal with company money. He and his Shuswap guides spent the summer of 1881 searching for a route through the western side of the Selkirks. Major Rogers climbed to the top of Selkirk barrier from the east side the next summer and confirmed the existence of a pass that he had spotted the year before. For his efforts, Major Rogers received a $5,000 cheque and a permanent place in Canadian geography.

By the end of the construction season just two years later, the right-of-way had been opened up as far as the newly-named "Rogers Pass". The end-of-track work camps were not far behind. James Ross supervised construction as his crews built eight major bridges east of the pass, including the Stoney Creek Bridge, (the tallest bridge structure in the world at the time), and the Mountain Creek Bridge (which required millions of board feet of lumber). The rail line was finished by the fall of 1885 and the last spike was driven at Craigellachie. Sir John A. Macdonald's dream of a trans-continental nation had been fulfilled within 14 years of his promise to British Columbia. The Pacific Express, the first transcontinental passenger service left Montreal on June 26, 1886, and arrived in Port Moody near present-day Vancouver on July 4.

An average of more than forty feet of snow fell on this rail line every winter it was in use. No trains ran for months in the first winter of operation, 1886-87. James Ross had warned Van Horne about the incredible snow depths and avalanche activity in Rogers Pass, finally convincing him to build a massive and expensive system of snowsheds, modelled after the Central Pacific Railway's sheds in California's Donner Pass. If building a railway through Rogers Pass was difficult, operating it turned out to be even worse. Early steam engines had difficulty climbing over the pass. Pusher engines were stationed east and west of the pass to assist trains over the steepest part of the route. Wooden bridges and trestles were eventually replaced with stone and steel structures to prevent their loss through fires. Rotary ploughs, invented in Ontario in 1885 and resembling a massive version of today's snowblowers, were added to the rolling stock in 1888. Even that was not enough to make Rogers Pass operations easy, as trains were regularly hit and derailed by sliding snow. Despite the incredible challenges however, the mainline was considered to be a international railroading triumph.

We plunged into the 26,517 foot Connaught Tunnel. On April 2, 1914, construction began on the Connaught Tunnel under Rogers Pass in the Selkirk Mountains, which would carry the Canadian Pacific Railway main between Calgary and Revelstoke and was built to replace the railroad's previous routing over the sometimes hazardous Rogers Pass. The tunnel, measuring five miles, was named in honour of Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, who served as the Governor General of Canada at that time. The Connaught Tunnel was completed ahead of schedule and it opened for use starting in December 1916. At the time of its debut, this structure was the longest railway tunnel in North America. The Connaught Tunnel was inducted into the North America Railway Hall of Fame in 2001 in recognition of its significant contributions to the railway industry.

Trans Canada Highway 1 passing through a snowshed. We ran up through the beautiful Albert Canyon and the line became single track at Illecillewaet as we passed through the Laurie Tunnels and snowsheds.

We travelled along Flat Creek and had eight more beautiful snow-covered miles to Glacier where it was snowing.

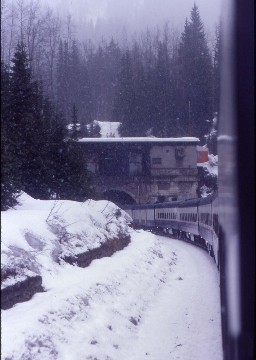

Passing through Glacier during a brief snowstorm.

Approaching the Stoney Creek bridge. Originally a wooden bridge constructed in 1885, Stoney Creek was the highest timber bridge ever built, and at the time was the second highest bridge in North America with reference to deck height, rather than structural height. Deck height is the maximum vertical drop from the bridge deck to the ground or water surface below. The confined workspace of the narrow gulch and the unstable rock foundation slowed construction and a flash flood, which buried the foundations of the high tower, cost two days of work. After a forest fire consumed 14 cars of lumber for the bridge, loggers had to fell additional trees to replace the loss. Completed in early August 1885, construction took seven weeks, which included ten days lost owing to the death of two workers and wet weather. Although each of the very high bridges on the east slope of the Selkirk Mountains had been construction challenges, this final one proved the most problematic.

No other railway has ever matched Canadian Pacific in building as many high timber bridges as were required to initially conquer the mountainous terrain of eastern British Columbia. Construction of a steel replacement began in 1893 when 3,000 carloads of rock were railed from a Salmon Arm quarry. During construction, a carpenter struck by dislodged rock sustained fatal injuries on falling to the bottom of the ravine. A Hamilton Bridge Company employee fell to his death later that year. This company replaced the existing crossing with a 270 foot high, 486 foot-long structure, incorporating a 336 foot steel arch span. After load testing, work was suspended until the spring 1894 completion and opening. The design could comfortably support the combined weight of two mountain region locomotives.

To handle heavier locomotives, the railway proposed to replace the structure with a new 311 foot cantilever deck truss with 111 foot flanking anchor spans, built adjacent to the existing bridge. However, the unsuitable rock foundation of the canyon made the idea uneconomical. Instead, truss arches, positioned outside of the existing ones, would widen each side by five feet. In 1929, the Canadian Bridge Company undertook the installation, and replaced the deck lattice girder spans with deck plate girders, which could support four locomotives with a combined weight of 1,100 tons. In 1970, the load capacity was re-evaluated for the introduction of bulk commodity unit trains and in 1999, another strength evaluation was conducted.

Crossing the Stoney Creek bridge.

Looking up Stoney Creek.

Rogers, where the new line through the Mount MacDonald Tunnel Line meets the original Canadian Pacific line. Far below is the westbound line that the railway built which uses the Mount Macdonald Tunnel, the longest rail tunnel in North America.

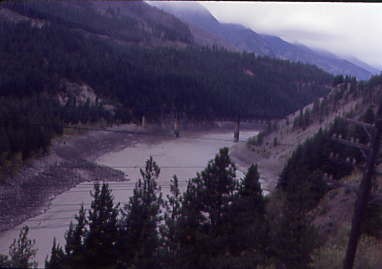

We followed Beavermouth River downgrade through Griffith and Rogers to Beavermouth and the junction with the Columbia River again, as the river's course took it far to the north and was now descending from the southeast. The river has Mica Dam downstream and since the spring runoff had not yet occurred, the river level was down.

The Columbia River again after it flowed north while we crossed Rogers Pass.

The beautiful colours of the Columbia River.

A look to the southeast with the river in the foreground.

We passed through another pair of tunnels, the first one named Calamity because of the number of people killed when construction was occurring, and the second was called Redgrave Tunnel, named for a member of the 1862 Overlander Party. We crossed the Columbia River for the last time before passing through Donald and Moberly prior to stopping in Golden to drop off a dead-heading freight train crew.

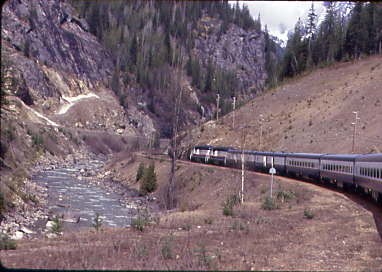

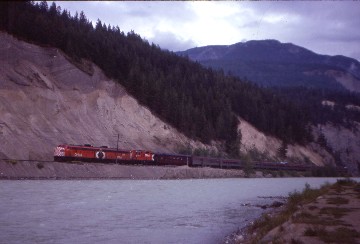

Well, I may not be on the Canadian riding by this location, but I would take this train any day of the year. We entered Kicking Horse River Canyon, crossed the river seven times in the narrow confines and passed through five tunnels and rock detector fences along its sheer cliffs.

Entering the Kicking Horse River Canyon.

The train twisted and turned as it climbed along the Kicking Horse River.

The colourful green waters of the Kicking Horse River. The river earned its name in 1856. A young Scottish explorer, James Hector, was propelled into the swift and swollen river courtesy of a mighty kick from his angry and tired packhorse. The kick to his chest rendered him unconscious for two hours, with a pounding headache lasting for several more. The event was sufficiently noteworthy for his travelling companions to change the river's name from its original Stoney First Nations ‘Wapta’ to ‘Kicking Horse’.

The Kicking Horse River and its tributaries (the largest being the Yoho River) drain a spectacular landscape of massive icefields, canyons, gorges, cliffs, avalanche slopes and mountain peaks ranking amongst the highest in the Canadian Rockies. The river system is fed by small timberline lakes and glacial meltwater streams with colourful names such as Ottertail, Otterhead and Beaverfoot. The river's personality varies with turbulent rapids, jaw-droppingly beautiful waterfalls and braided streams meandering through valley flats near the town of Field. In 1990, the Kicking Horse River was designated as a Canadian Heritage River for its historical, cultural and recreational significance, one of only three in British Columbia.

The many views of the Kicking Horse River Canyon.

Mount Burgess ahead.

Rounding a curve with Mount Burgess in view.

I was completely in awe as I took these pictures. After passing through Ottertail, we crossed Boulder Creek and a few minutes later, arrived in Field for another crew change stop.

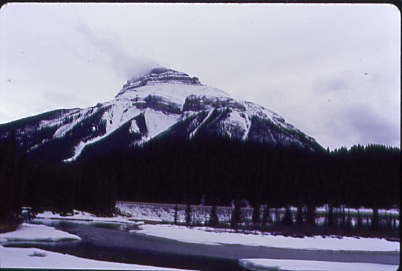

Mount Stephen as the train approached Field, our train crew-change location.

Canadian Pacific 9526 East waited for us to leave.

Mount Field.

Climbing Kicking Horse Pass.

Exiting a tunnel and snowshed.

Curving into another tunnel.

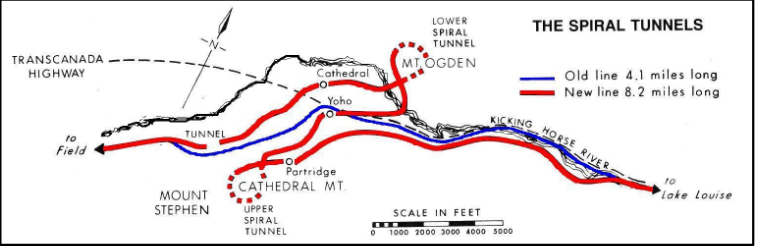

Once on a ledge, we passed through tunnels and snowsheds before reaching Cathedral siding then entered the Lower Spiral Tunnel inside Mount Ogden, turning 226 degrees to the left before exiting to a fantastic view where the tracks that we had been on were right below. A passage through the Spiral Tunnels was something I had always wanted to do

Above the Spiral Tunnel.

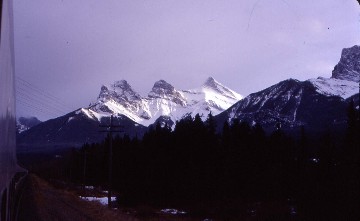

The beautiful peaks of the Canadian Rockies.

Looking back down on the track on which we came to the Lower Spiral Tunnel.

Looking down the mountain at the Lower Spiral Tunnel.

Entering the Upper Spiral Tunnel. We turned to the right to reach Yoho Siding before reaching the bottom portal of the Upper Spiral Tunnel, turning 288 degrees to the right and exiting again to another fantastic view and our former route below. After travelling through the Spiral Tunnels, my one word was 'incredible' for this engineering feat.

West of Hector (near Wapta Lake in Yoho National Park) the new Canadian Pacific Railway transcontinental main line was first planned to descend for 23 miles to the valley floor at Ottertail, 7 miles west of Field, BC, on the "high line", a steady 2.2 percent grade along the mountainside, in accordance with the terms of CPR's charter for building the line. This would have taken years to build across avalanche paths and through a 1,400 foot rock tunnel in Mount Stephen, so in 1884 a temporary main line was built on a steep, 4.5 percent grade, aptly named the "Big Hill", from Wapta Lake to east of the present day site of Field (near the concrete slide shed). This allowed construction to continue and the railway to open for service without delay. For 25 years, the CPR operated trains on the Big Hill with helper locomotives and they were looking for a solution to the serious and costly problems of inefficiency in eastbound (uphill) train operations and safety in westbound (downhill) operations.

Railway civil engineer John Edward Schwitzer had the solution to the problems. Born in Ottawa in April 1870, Mr. Schwitzer entered the service of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1899. In only eight years at the railway, Mr. Schwitzer rapidly rose through the ranks to the senior engineering post on CPR's Western Lines. It was in this position that he was confronted with the challenging task that would lead to a spectacular engineering accomplishment. The solution proposed by Schwitzer to eliminate the steep grade of the Big Hill was based on the Swiss example of "spiral tunnels". Specifically, the line was doubled back upon itself to create four new miles, allowing a more leisurely grade than the "Big Hill" afforded. The new eight mile alignment, upon which work began in 1907, followed a consistent grade of 2.2 percent. The net effect was to add capacity to the CPR main line, as it not only increased the capacity of contemporary locomotives in terms of hauling power, but provided for safer and additional train operations over this section of the line.

The contract for construction of the tunnels was awarded to MacDonnell, Gzowski and Company of Vancouver and work started in 1907. The labour force amounted to about a thousand and the cost was about 1.5 million Canadian dollars. The construction included the boring of the 179 foot long tunnel through the nose of Cathedral Mountain, 1.5 miles west of the Lower Spiral Tunnel, as well as building of the 8 miles of new grade. Over the years, CPR has incurred additional expense in lining the tunnels with concrete, enlarging the bore size to accommodate double-stack container trains and replacing the wooden ties with steel ties to reduce maintenance requirements.

As completed, the Upper Spiral Tunnel through Mount Cathedral was 3,255 feet in length carrying the track through 288 degrees of curvature and a difference in elevation of 56 feet. The Lower Spiral Tunnel, through Mount Ogden, was 2,922 feet long, possessing 226 degrees of curvature and a vertical difference of 50 feet. Apparently no photographs exist of the tunnel under construction. The now famous "Spiral Tunnels of the CPR" saw their first traffic on 01 September 1909 and continue to be an integral part of the CPR's main line operation today. The portion of the 1884 'old line' railway route from Wapta Lake to Cathedral was used for construction of the Trans-Canada Highway in the 1950s. The Town of Field, which was a major hub of railway activity in the days of steam locomotives, continues today to serve in a much diminished role as a CPR division point for Calgary and Revelstoke crew changes.

Schematic of the 1884 Old Line, 1909 New Line & Spiral Tunnels, 1950’s Trans-Canada Highway. From "Canadian Pacific in the Rockies, Vol. One", page 2 by Donald M. Bain, 1978, published by British Railway Modellers of North America.

The above passage and schematic taken from Canadian Pacific Railway Spiral Tunnels Centennial by Cor van Steenis, a special report for Canadian Railway Observations.

Mount Field, named in 1884 after Cyrus West Field, an American merchant who had laid the first Atlantic cable in 1858 and a second in 1866. Mr. Field was visiting the Canadian Rockies that year as a guest of the CPR who were building the national railway, at the naming of a station and a mountain. It is 8,671 feet in elevation.

Mount Niblock was named in 1904 after John Niblock, a superintendent with the Canadian Pacific Railway. Niblock was an early promoter of tourism in the Rockies and influenced the naming of some of the CPR stops in Western Canada. It stands at an elevation of 9,764 feet.

Kicking Horse Pass with Mount Field.

Vanguard Peak of Cathedral Mountain. We passed through Stephen before reaching the Continental Divide at Kicking Horse Pass.

Running below beautiful mountains.

The late-day sun showing through the clouds over the beautiful peaks.

The train along the Bow River at Morant's Curve. Nicholas Everard Morant, CM (29 June 1910 – 13 March 1999) was a Canadian photographer who produced iconic images of the Canadian Pacific Railway. As the special photographer of the Canadian Pacific from 1929 until 1935, and then again from 1944 until his retirement in 1981, his work was especially influential in promoting tourism in Western Canada and the Canadian Rockies and included many images of the Canadian Pacific's flagship streamliner The Canadian.

One of Morant's favourite shooting locations was located in the Canadian Rockies east of Lake Louise, Alberta where the CPR mainline parallels the Bow River. This location now bears the geographic placename Morant's Curve in his honour. His images were not only used in promotional material for the railway but also were used subsequently in Canadian currency and postage stamps. His images also appeared in Time, Life, National Geographic, Reader's Digest and The Saturday Evening Post.

The sun, the mountains and the author having a fantastic time aboard the Rocky Mountaineer.

Here the Canadian Pacific has another westbound grade separation that runs down to Lake Louise with its log depot.

The peaks with a bit of clouds.

Castle Mountain at 9,075 feet, is located within Banff National Park in the Canadian Rockies, approximately halfway between Banff and Lake Louise. It is the easternmost mountain of the Main Ranges in the Bow Valley and sits astride the Castle Mountain Fault which has thrust older sedimentary and metamorphic rocks forming the upper part of the mountain over the younger rocks forming its base. The mountain's castellated, or castle-like, appearance is a result of erosive processes acting at different rates on the peak's alternating layers of softer shale and harder limestone, dolomite and quartzite.

The mountain was named in 1858 by James Hector for its castle-like appearance. From 1946 to 1979, it was known as Mount Eisenhower in honour of the World War II general Dwight D. Eisenhower. Public pressure caused its original name to be restored, but a pinnacle on the southeastern side of the mountain was named Eisenhower Tower. Located nearby are the remains of Silver City, a 19th-century mining settlement, and the Castle Mountain Internment Camp in which persons deemed enemy aliens and suspected enemy sympathizers were confined during World War I.

An interesting peak.

The peaks to the north.

A look back at our train and the peaks.

A lake with the mountains reflected in the water.

The town of Banff, Alberta.

The two-storey Canadian Pacific Railway station at Banff, constructed in the Arts-and-Crafts style in 1910 and served the railway's Banff Springs Hotel. It was declared a heritage railway station by the federal government in 1991. Here, the majority of passengers detrained to enjoy Banff and the surrounding area.

The peaks standing against the sky.

A lone peak on a ridge.

We passed a frozen lake.

Passing another lake on our way east.

The rest of the trip was peaceful and I rode in the vestibule until we were out of the mountains, where I returned to my coach seat to enjoy the rest of the journey.

The Rocky Mountaineer approaching Calgary in the last light of day.

We followed the Bow River to Calgary, where we arrived at the former Canadian Pacific station next to Calgary Tower. As I detrained, I said goodbye to all my new friends before going next door to the Fairmont Palliser to spend the night in this former Canadian Pacific hotel. I watched the end of the first period of the Detroit Red Wings-Los Angeles Kings playoff game and learnt the next morning that the Kings won 4-3 in overtime, tying the series at two games apiece. With the excitement of the day, I had no difficulty falling asleep and slept the night away soundly.