The purpose of this trip was threefold. Firstly, and most importantly, to ride what was left of the original California Zephyr, the Rio Grande Zephyr, before it ended on April 14th. Secondly, I planned to visit my brother Bruce in Pocatello, Idaho and thirdly, I wanted to sample some new routes, namely Amtrak's San Joaquin, San Francisco Zephyr, Rio Grande Zephyr and the Pioneer. To accomplish all this, I bought my first All Aboard America fare, which allowed me to go to Phoenix two weekends later.

Southern California was at the end of one of its wettest winters in history thanks to El Niño. Santa Ana received over thirty-eight inches of rain and the last storm blew through on the night I arose at 11:30 PM so my father could drive me to Los Angeles Union Station to meet the San Joaquin Thruway bus for Bakersfield and the train. I boarded the bus, concentrating on the train ride which lay ahead and managed to nap with the next thing I knew being our approach to the Bakersfield Amtrak station trailer.

San Joaquin 711 3/26/1983

I chose the early morning train in order to connect with the City of San Francisco at Martinez and had ridden the valley route many times, but never on a train and certainly not the train's route. The highway went via the straight route to the major cities, as does the Southern Pacific line which was built first, but Amtrak uses the Santa Fe's route, thereby providing better track, higher speed and better train handling. I settled in to my Amfleet coach and we were off on time and sprinted up the San Joaquin Valley.

The valley was a vast garden in a desert with water brought to where the farmers need it and without the benefits of irrigation, this would be just another huge desert valley. Once out of Bakersfield, the train crossed the Kern River, skirted refineries, passed through orchards and fields before going through Shafter on the way to the first at Wasco. North of there, there were miles upon miles of flooded fields and nothing outside the windows except roads, which were built higher than the fields, and were covered with water. The train had to slow because water had been lapping up against the right-of-way and damaging it but once we reached Corcoran, we left the lake district of the valley and returned to the more normal fields and orchards.

At Hanford, a large group of people boarded on this Saturday morning with most going to the Bay Area for the weekend. The Fresno stop was no different and it was now a full train, then we crawled down the middle Q Street and North Davis Street until we reached the private Santa Fe right-of-way. We crossed the San Joaquin River which was running high then returned to the normal valley scenery where this middle portion was clear and to the east I could see the snow-capped peaks of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, which I was going to cross further north this afternoon. We stopped at the Amshack at Madera on the outskirts of town before passing miles of pastures with cattle and through the little towns of La Grand and Planada.

Upon our arrival at Merced, a group of twenty-five detrained for the bus to take them to Yosemite National Park. These buses, also named San Joaquins, are part of a network of feeder bus routes which bring or take passengers from the train, thereby adding many destinations apart from those only served by the train, in my case Los Angeles, as well as Sacramento. I was amazed by the train's speed of a consistent seventy-nine miles an hour except in towns and curves and it was a flat run with the exceptions being the rivers which have cut down into the valley's floor. The Merced River was crossed on high bridges then at Empire, I saw a Modesto and Empire Traction Company train pulling eighteen box cars for interchange with the Santa Fe. Speeding north, Riverbank was our next station which served Modesto then between there and Stockton, we met our sister southbound train.

West of Stockton, the train entered the delta region of California, the point where the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers meet and join, flowing west to form Suisan Bay, then flow through the Carquinez Straits into San Pablo Bay, the north end of San Francisco Bay. We crossed the delta on fills and two drawbridges and under normal circumstances, the fields, which had been reclaimed from the water, are dry, but today, were underwater from all the excess rain. This year's mud slide season lasted a little longer and was a lot heavier than normal. We left the delta and passed through the bayside city of Antioch and slowed to change railroads at Port Chicago. This was the site of a deadly munitions explosion on July 17, 1944 when munitions detonated while being loaded onto a cargo vessel bound for the Pacific Theater of Operations, killing 320 sailors and civilians and injuring 390 others. Most of the dead and injured were enlisted African-American sailors. The town of Port Chicago was heavily damaged by falling debris, including huge chunks of hot metal and unexploded bombs, but none of those bombs exploded. Over 300 buildings were damaged and more than 100 people were hurt, but none in the town were killed. In 1968, all property was acquired and the buildings subsequently were demolished by the federal government to form a safety zone around the adjacent Concord Naval Weapons Station loading docks.

We switched from the rails of Santa Fe to those of the Southern Pacific for the rest of the journey and followed the bay along its shoreline, where I detrained at Martinez and stored my bag behind the station counter and walked across the street to a hot dog stand for an early lunch. I returned to the station, retrieved my bag and waited eight minutes for my next train.

The City of San Francisco 6 3/26/1983

The City was one of the first jointly-operated streamliners in the country, running between Chicago and Oakland over the tracks of the Chicago and North Western (later the Milwaukee Road), Union Pacific and Southern Pacific. When Amtrak was formed on May 1st, 1971, this route was selected for their train service because not only did Denver and Rio Grande Western refused to join Amtrak, choosing to operate a Denver-to-Salt Lake City train but to serve Reno, Nevada while east of Denver, the train would be run over the rails of the Burlington Northern to Chicago.

Standing on the platform, I heard a whistle then saw the train curving around into the station. I went upstairs into the Superliner coach and found a seat, settled in and had my ticket taken just as the train crossed the Carquinez Straits drawbridge between Martinez and Benicia. As we descended the grade from the bridge, to the right was the mothballed fleet of the United States Navy in Suisan Bay. The City next stopped at Suisan-Fairfield to pick up a single passenger, continued to Davis and crossed the Yolo Bypass which was full of water for the entire four mile crossing. This bypass takes the excess water from the Sacramento River and lets it flow in almost a straight line to the delta, reducing the possibility of flooding in the main channel through Sacramento. When it is dry, farmers use it to grow crops so this land serves a dual purpose.

We picked up speed after the bypass, going through West Sacramento and crossed the Sacramento River on a drawbridge, where the California State Railroad Museum was on the right, then stopped at Sacramento station. Here, Pat Flynn, a Western Pacific dispatcher whom I had met at Winterail, boarded and we went to the Sightseer Lounge Car. Chatting about our travels, we realized we were travelling the same trains, specifically the City of San Francisco to Denver and the Rio Grande Zephyr to Salt Lake City, where we would split as Pat was returning to Sacramento and I was going to Pocatello on the Pioneer. The train passed through the vast Roseville yard where the snow-fighting equipment had been in great demand this winter season. Since one inch of rain equals six inches of wet snow or thirty inches of dry snow, thirty-eight inches of rain in Santa Ana would have had two 228 inches of wet snow or 1,140 inches of dry snow.

East of Roseville lay Donner Pass, one of the snowiest areas in the United States. The record snowfall for the Summit area was reached at Norden near Donner Summit in 1952 with 790 inches. With the rainfall we had this year, I was looking forward to my first journey over the Pass and seeing my first deep snow, all from the warmth of the train. The double track main line split east of Roseville and the eastbound trains took the newer and longer grade, while the westbound trains takes the original steep grade, which was built by the Chinese as part of the first Transcontinental Railroad by the Central Pacific. The area it crosses is full of historical information from the early settlers to the Gold Rush and the building of the railroad. We would climb to almost 7,000 feet from Roseville to Donner Summit on a two percent grade.

The train curved through Auburn, affording me another view of the snow-capped Sierras and my excitement began to build. The countryside had changed from the valley floor to oak treed hills and pine trees slopes. Climbing a mountain akin to travelling a thousand miles to the north from a starting point since the further north one travels, the vegetation changes in the same manner when you climb a mountain. The two tracks rejoined each other as we arrived at Colfax, where a set of helpers waited to push a freight train up Southern Pacific's big hill; some trains receive their helpers here while the really heavy ones receive theirs at Roseville. The train next curved to cross the bridge over Long Ravine before rounding Cape Horn with the view of the American River far below and passenger trains used to stop here to let the passengers take in the view.

The line was engineered to follow the ridge lines up towards the summit so that the line would always be gaining altitude and it was cut out of the mountain's side with picks and shovels. Chinese workers were hung over the ledges to cut out the railroad's path and early dynamite was used for blasting out ledges and tunnels, with many men giving up their lives for the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad. If the terrain was not bad enough, add in the weather and the snowfall and wooden snowsheds, basically a roof over the railroad, were built in the heaviest snow areas, which were susceptible to fire. At one time, the railroad had over 32 miles of track protected by snowsheds but by 1952, there were only five-and-a-half miles left. Today, all are concrete and are only where absolutely necessary.

The City of San Francisco arrived at the snow line and we passed through the former gold-mining towns of Alta and Gold Run as the snow grew deeper. It was absolutely beautiful the way the snow covered the buildings and trees, giving the area a winter wonderland feel, even in April. Icicles hung from where the snow had melted and the drips were re-frozen each night making them longer. The train neared Emigrant Gap, a low spot of the ridge where the railroad switched from the south to the north and we ran for a few miles in the shadows of the ridge before curving into Yuba Gap, the site of the only train to become snowbound in the history of Donner Pass. In 1952, the City of San Francisco was westbound in a terrible storm and the train, pulled by diesel locomotives, arrived at Yuba Gap westbound, struck a slide and was trapped by the snow. It continued to snow harder and it was only through the rescue efforts of locals, along with Southern Pacific employees, that every passenger aboard survived. The total snowfall for the 1951-1952 season was 790 inches, enough to cover a five-story building. I thought of that story and was glad to be in a nice warm Superliner Lounge Car passing the deep snows at that very snowbound spot.

Past Yuba Gap, we travelled through a series of tunnels and then a few of the remaining snowsheds. The clouds had lowered or perhaps that was from the fact that we were so high, and the snow was about halfway up the side of the cars so anyone on the lower level had a pure white view. At Soda Springs, a road to a ski area crossed the tracks with many skiers waiting for our train to pass then just before Norden, we came to a road crossing with a high wig-wag signal but of course there was no road visible, just the wig-wag swinging back and forth through at least thirteen feet of snow, the deepest I had seen. This experience gave me a complete understanding of the beauty and reality of winter railroading. At Norden, we entered a snowshed complex with a turntable, beanery, trainorders office and crew quarters for the snow fighters, all protected from the climatic elements then burst back into the fresh mountain air for several minutes before plunging into the Summit Tunnel under the summit ridge of Donner Pass. We left the tunnel and descended the east side of the Sierras via Coldstream Canyon with Donner Lake to the left.

This whole area was named for the ill-fated Donner Party, who, during the severe winter of 1846, attempted a late-season crossing of the pass in late October after a snowstorm had already closed it. Of the eighty-two settlers from Illinois, only forty-seven survived by camping at the east end of Donner Lake eating twigs, mice, their animals, their shoes and finally their own dead. Fifteen people tried to cross the pass in late December in the hopes of bringing back a rescue party, but only seven made it through. Those rescuers could only save forty people by the time they reached them.

Arriving at Truckee, the lights of the city began to take hold as darkness settled in on the valley. We followed the Truckee River, one of the few large rivers in North America that does not empty into an ocean, to a point near Lovelock, Nevada, which was far out in the desert. We curved downstream along its course and an hour later, arrived in Reno, "America's Biggest Little City." We passed through an area which was fully lit from the bright neon lights of the casinos but once away from there, it was like any other western town. My reservation for dinner was called so I went to the dining car and ordered a steak then we departed Reno and travelled the few miles to Sparks, a crew change point, where the train was serviced and the Reno coach removed. With the train's power cut, I dined by yard floodlight which was an experience, then returned to my coach seat and as the train passed Lovelock on its way into central Nevada, I called it a night and fell fast asleep.

3/27/1983 At 4:00 AM, I went downstairs to find the conductor standing with the vestibule window open and he invited me to enjoy the crossing of the Great Salt Lake. The original transcontinental line ran around the north end of the lake up on the slope of Promontory Mountain, so in 1903, Southern Pacific built the Lucin Cutoff with a trestle across the middle of the lake. This was replaced with the fill completed on July, 9, 1959 by Morrison-Knudsen at a cost of fifty million dollars, on which we were riding on this pre-dawn morning. As I looked out at the lake's vastness, the wind was really whipping up the waves and crashing against the fill. Just as Donner Pass was known for snow removal, this area of the Southern Pacific was a battle against water. With the recent wet years, the lake was at an all-time high and Southern Pacific feared losing the battle. But we made it across and arrived at Ogden, Utah fifteen minutes early.

It was the moment before sunrise and the high clouds were coloured with a brilliant red with the wind still blowing cold as I stepped off to stretch my legs at Ogden Union Station. I grabbed a newspaper while Union Pacific added an SD40-2H freight locomotive to the point of our train and I noticed about twenty-five people boarding a bus bound for Salt Lake City, most of whom would be riding the Rio Grande Zephyr later in the morning. I, however, was taking the quicker route through scenic Wyoming to Denver and remembered just how wide open it was during a family camper trip across Wyoming as a child and wondered if it would be as wide open today.

Leaving Ogden, we were now riding on the rails of the other transcontinental partner, Union Pacific. They built west from Council Bluffs in the late 1860's, meeting the Central Pacific at Promontory Point on May 10th, 1869. This was the route of the legendary City trains which Union Pacific operated to every major city on their system. The City of San Francisco, with the Southern Pacific west of Ogden, City of Los Angeles, City of Portland and the City of St. Louis, with a Wabash connection east of Kansas City. Those trains were some of the finest left when Amtrak took over and showed the pride Union Pacific took in running their passenger trains.

Travelling east from Ogden after passing through the yard, we followed the Weber River into the Wasatch Mountains and gained elevation in order to reach the Wyoming plateau. The lower canyon was tight with steep sides, one area was called Devil's Slide, before it opened into a nice valley with snow-capped peaks near Morgan. The mountains at Alta and Park City provided some of the best skiing in the west then we travelled through Echo Canyon with its beautiful red sandstone cliffs. The double track main line then split, with the eastbound track crossing over the westbound at Curvo before passing through a long tunnel and reaching the summit of the climb at Wasatch. We crossed the state line into Wyoming and arrived at Evanston, our first station in the state. This was my first time in Wyoming by rail.

So far this morning, we had Interstate 80 within sight but departing Evanston, we proceeded southeast while the highway took the short way out of the Bear River Valley. To leave the valley, we plunged into the long Altamont Tunnel and upon exiting, three freight trains flew by on the opposite track mere few minutes apart. Freight trains would be the order of the day as this was Union Pacific's main line across the country. At the town of Granger, the Union Pacific line from the Pacific Northwest joined the route, so now the tracks carried all Union Pacific traffic to the west. The train descended the long grade to the crossing of Green River and stopped at its namesake city, then upon departing the beautiful red brick station with its white columns, we passed through the freight yard and followed a small stream out of town. Fifteen minutes later, our next stop at Rock Springs came and went then continuing east, we encountered the Continental Divide twice as the railroad descended into a basin with no watery exit and a dry lake in the middle, before ascending the other side and crossed the divide for the second time. In the middle of the basin, we passed a large herd of elk and I was amazed by their numbers and it made me wonder what a herd of buffalo must have looked like when the railroad was being constructed across the plains in the 1860's.

Our new crew had been pointing out the many scenic highlights as well as numerous recent Union Pacific projects. Passing Tipton, it was revealed that the last train robbery in the state committed by the Hole in the Wall Gang of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid occurred here. We arrived at Rawlins and after a brief stop, continued our trek east then at Sinclair, we passed the refinery of the same name with its "flare off" burning against the wide Wyoming sky. The remains of Fort Steele were passed a little later on the left, followed by Walcott, the other location where the Hole in the Wall Gang pulled off what became the largest train robbery in the Union Pacific's history. We then passed the boom town of Hanna with its strip coal mines and fifteen miles down the tracks, flew through Medicine Bow. The North Fork of the Platte River, which we had been following since Rawlins, turned north as we turned to the southeast and went by the snow fences, then within an hour, we arrived at Laramie ten minutes early.

East of there was a section of track over which I had always wanted to ride. Sherman Hill, the highest point on Union Pacific's main line, was also the first obstacle the westward builders faced since they wanted to build west as fast and as inexpensively as possible, so they surveyed the same route that the Indians had been travelling for centuries. The climb over Sherman Hill could have been avoided if they had followed the North Platte River and although it was a longer route, it would have all been at water level around this ridge then rejoined the present route at Medicine Bow.

Leaving Laramie, the tracks split and our train started its ascent on the shorter grade of the two at 0.82 percent and began to pass rock outcroppings. At Colores, we passed the usual cliff-like formations followed by the many snow fences and the trees were all stunted in their growth due to the high winds. The train continued to climb until it reached Hermosa, where the two lines rejoined before they plunged into the twin bores of the Hermosa Tunnels, the only tunnel on Sherman Hill. We crossed Dale Creek on a high fill and passed through Dale, the junction with the newer westbound line built from Cheyenne in 1952 with a lower gradient. Passing more odd rock formations, off in the distance was Ames Monument, a pyramid to the memory of Oaks Ames in recognition of his services in the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad. A little further, the climb ended at 8,013 feet at Sherman then as we descended the east face of Sherman Hill, we passed the large ballast pit at Buford and continued down the 1.5 percent grade to our next stop fifteen miles away at Borie, which is the stop for Cheyenne and nothing more than a windswept platform in the middle of nowhere.

We followed Lone Tree Creek to take us to the Colorado border, swung off the Union Pacific main line onto the Borie Cutoff to reach Denver then met the low grade line at Speer and proceeded south to Colorado. The sky was turning red as sunset arrived, giving the snow a reddish tint. I went to the dining car and had chicken as I watched the sun set over the Rockies then Greeley arrived in darkness and was followed by an on-time arrival in Denver. It was a quick taxi ride to the Travelodge, where I freshened up and retired for the night.

Rio Grande Zephyr BackgroundThe Rio Grande Zephyr was a remnant of the former California Zephyr, covering only the Rio Grande's portion of the route. The California Zephyr, operated jointly by the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy, the Denver and Rio Grande Western and the Western Pacific, had made its last through run on March 22, 1970. After that, Western Pacific no longer participated in the train's operation but the Burlington continued operating their portion from Chicago to Denver as the "California Service". The Rio Grande created the Rio Grande Zephyr and extended it from Salt Lake City to Ogden, which linked the Burlington's train at Denver and allowed passengers to continue westward on the Southern Pacific and Union Pacific trains at Ogden.

Nearly every other railroad turned over their passenger operations to the newly-created Amtrak on May 1, 1971. Even the Rio Grande had considered joining, but shortly before Amtrak was set to take over, opted to continue operating their own trains. The reasoning behind this decision was purely financial since part of joining Amtrak was paying a sum equal to what it lost on passenger operations in an average year, as well as negotiating ongoing payments equal to the incremental cost of running passenger trains. Cost sharing for regular maintenance and upgrades was not allowed, only incremental cost of wear/tear on the track by Amtrak's trains for example. Amtrak and the Rio Grande could not come to terms on a contract and at that point, the Rio Grande apparently calculated that the costs of running the Rio Grande Zephyr would be less than what they would have to pay Amtrak.

Amtrak launched its version of the old California Zephyr on day one, calling it the San Francisco Zephyr. The train would use the old Burlington Route into Denver and then turn north and travel to Salt Lake City via the Union Pacific's Wyoming mainline, known as the Overland Route. West of Salt Lake, the train would not follow the traditional California Zephyr route via the Western Pacific, but rather the Southern Pacific.

For just slightly over thirteen years, the Rio Grande Zephyr made tri-weekly trips between Denver and Salt Lake City. Equipment was largely leftovers from the California Zephyr, heavy on dome cars and with sleepers converted back into coaches, as the Rio Grande Zephyr easily made the run as a day trip. The tri-weekly schedule took only six days (one day each way for three trips) and always excluded Wednesday. Hence, the train is often associated with the motto, "Never on Wednesdays". On April 14, 1983, the last full run of the Rio Grande Zephyr would be completed. The westbound Zephyr passed Thistle, Utah at 8:30 PM and shortly afterwards, the line was severed by the Thistle Mudslide. The train, like all other end-to-end Rio Grande traffic, returned to Denver via Wyoming, detouring over the Union Pacific. Afterwards, the Rio Grande Zephyr trainset would continue making a handful of runs to Grand Junction, but Rio Grande passenger operations were winding down.

On April 24, 1983, the Rio Grande ran its last Rio Grande Zephyr, and at last relented and joined Amtrak. It would be nearly three months before Amtrak began using the traditional route and with the train re-named the California Zephyr again, the first eastbound originated from Chicago on July 15, 1983 and passed the site that killed its predecessor the following day.

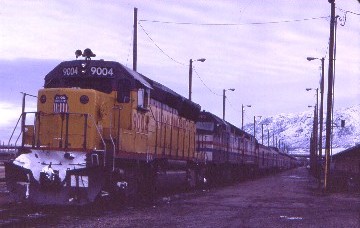

Rio Grande Zephyr 17 3/28/1983I awoke to a beautiful clear sky and I was caught up in the excitement of what lay ahead, a ride on the last non-Amtrak train in the United States. A quick taxi ride to Denver Union Station followed and I was greeted by a mob in the waiting room with most passengers bound for Glenwood Springs, the most popular destination on the route. The Salt Lake City passengers boarded first and I walked with thirty-eight others to coach 1121 "Silver Pine", built by Budd Company in 1948 as a sleeper then converted to a 48-seat coach in 1964. In 2010, it was acquired by Austin Steam Train in Cedar Park, Texas.

The train consisted of an A-B-B set of F-units, a steam generator car, a combine, dining car 1115 "Silver Banquet", four dome-coaches including 1108 "Silver Pony", two regular coaches and dome-observation 1145 "Silver Sky". I chose a seat on the left side but naturally did not plan to sit there with a choice of five dome cars in which to ride. The conductor took my ticket and told me the whole train was mine to enjoy so I walked back to "Silver Sky", just as business car "Wilson McCarthy" was added to the rear, thus blocking the rear view "Silver Sky" would normally offer. At precisely 7:30 AM, the train whistled off and my journey on the last great non-Amtrak train began.

Returning to "Silver Pine", which featured large windows so my views left and right were plentiful and I enjoyed the passage through North Yard, Rio Grande's main Denver yard and then the suburbs of the mile high city. The train quickly passed through Leyden then slowed as it climbed to Rocky, where we met an eastbound freight. Knowing that the Big Ten Curve was next, I returned to the dome of "Silver Sky" and knelt in the aisle at the front.

On the approach to the Big Ten Curve. Rising out of the plains at the front range north of Denver, the railroad makes a long slow curve of 270 degrees. Called the Big Ten, because the radius of the track's curve is ten degrees, based on the method railways uses to measure curves. Built in the early 1900's, this section of track was once the Denver and Rio Grande Western, now Union Pacific. In the middle of the curve is a row of about two dozen hopper rail cars filled with cement. In the early 1970's they were permanently parked on a separate track inside the curve and welded to the track, to serve as a windblock in this notoriously windy and snowy stretch of track.

At the bottom of the curve.

On the bottom of the curve.

As the train ascended up and started its journey around, many photographs were being taken, then as we approached Clay siding, I was off in search of an open vestibule window and found one in "Silver Pony" so I could enjoy the climb to Moffat Tunnel in the fresh air.

At the top of the curve.

The top of the vestibule was open so I settled in there very happy, since this was the best place to ride on a train with the fresh air, the wind blowing through your hair and the unobstructed view. When the train curved, you receive an excellent forward view and can turn to see the rear of the train negotiating the same curve. This was the heaven of train riding and something not permitted on Amtrak trains.

The sun shone brightly across the snow-covered landscape with the train climbing higher and higher.

Looping around Coal Creek Canyon and entering tunnel one. Exiting the first of twenty-nine on the Front Range, I looked back at the Denver skyline through the early morning haze before it was back to the train as the climb continued.

At Plainview siding, we met another freight train waiting for us then travelled through two cliff-lined tunnels as we continued our two percent climb along the Front Range to reach South Boulder Creek with its access to the Continental Divide. Turning west along the creek, we popped into a tunnel, rounded a curve, entered another tunnel, followed by another curve and had one last view of the Great Plains far below. At Crescent siding, there was enough room for a brief piece of tangent track before returning to the twisting, turning and tunnels of this morning's run. Continuing west, we passed through Granite tunnel with a group of photographers high above.

Climbing past Pinecliffe siding, we passed a waiting westbound helper set then went up a tight valley and passed a few cabins before reaching Rollinsville.

I could see the divide ahead with its snow-capped peaks as we twisted and turned like a silver snake. The brakeman walked by and reminded me to close the vestibule before reaching Moffat Tunnel so as to keep the diesel fumes out of the train. He noticed that my upper lip was bleeding and told me he had an old fashioned cure to solve the problem after we exited the tunnel then went about his duties as the train arrived at East Portal siding, rounding a slight curve before making a beeline for the tunnel. At the west switch, I closed the vestibule and stepped into "Silver Pony" for eighteen minutes of darkness while the train passed through the tunnel at the highest point on today's route and under the Continental Divide. I walked up into the dome and enjoyed the passage before we exited the third longest railroad tunnel in the United States.

Bursting out into the bright mountain sunshine, we passed the Winter Park ski area where skiers were busy practicing their skills on this late March day. The brakeman returned with a shot glass of whiskey and told me to hold it up to my bleeding lip then stick my head out into the wind, which I did and my lip sealed. I asked him how he knew that would work and he said his grandfather worked on the Rio Grande and it happened all the time and that solution was the quickest. I asked him what I should do with the whiskey and he said that I could drink it if I wanted to.

The train followed the Fraser River into its valley to where it met the Colorado River, which we would follow for 238 miles. We stopped at Granby on time and were met by three cowboys on horseback then continuing west, we entered Byers Canyon with US Highway 40 on the opposite side and the friendly photographers, then another small valley. It was here I decided to go to the dining car for breakfast so walked through three dome-coaches and entered "Silver Banquet" to wait to be seated. Each table had white linens, a real flower, china and silver and the place setting was finer than any restaurant I had experienced. The steward seated me on the left side along a window facing forward and handed me a menu card and I ordered the Rio Grande Special which included chilled orange juice, French Toast with country sausage patties and a cup of tea. He finished taking my order and returned with a cup of tea and meanwhile, the train had entered Gore Canyon with its steep sides, slide detector fences and short tunnels. The river had a series of rapids, thus descending well below track level and my meal arrived and I savoured my repast, still eating as the train passed through Yarmony and Radium before I paid my bill as we passed State Bridge. I returned to my vestibule after the best breakfast experience I had had in my travels to date, and knew that it would be hard, if not impossible, to top.

The canyon opened a little at Orestod. To provide some context, aside from avoiding yet another mountain crossing and potential helper district, one of the reasons that the Denver, Northwestern & Pacific had chosen the route through Gore Canyon to McCoy was to provide the possibility of a short linkage with the Rio Grande. Following along the Grand (now Colorado) River canyon west from Bond, it was only a short 45 water-level miles over to a point on the Rio Grande's standard gauge mainline near the confluence of the Colorado and Eagle Rivers. Freight could then be sent west over the D&RGW to Salt Lake and, via sister road Western Pacific, the West Coast. Clearly this connector was far more practical than completing Moffat's dream of a railroad west from Craig, this would complete the line to Salt Lake with a minimum amount of work. This was clearly the better option. This new piece of railway would connect two points, Dotsero or Orestod (the names are perfect reversals of each other), and be known as the Dotsero Cutoff.

Despite the D&SL and the D&RGW having jointly chartered the Denver, Salt Lake & Western to build the cutoff in 1924, little happened until after the Moffat Tunnel's completion. The connection was initially just obvious for the D&SL - the additional bridge traffic it would pick up from the UP's Wyoming line and the Rio Grande's Tennessee Pass main would more than pay for the connection. However, all was not well - there was no real source of funding yet, and the Interstate Commerce Commission was concerned that a D&SL - D&RGW combination would eventually work to eliminate the Tennessee Pass line entirely. The ICC finally agreed that the D&SL would build the cutoff, and the D&RGW would assume ownership. A year or two later, however, both roads found it to be against their best interest - the D&SL now felt that insufficient traffic would surface to justify it, and now the Rio Grande feared it would eliminate revenues from haulage via Tennessee Pass and Pueblo.

Thus, neither road acted, and by 1928 when the tunnel was completed, there was absolutely no sign that either road was starting, or would ever start the Dotsero Cutoff. In 1930, after the Rio Grande petitioned the ICC to gain control of the D&SL, they agreed with one firm condition - the Cutoff must be started within six months and finished within two years. Seeing all the pieces for a competitive transcontinental route in place but not being finished bothered the ICC, and they agreed to this to force action on the Cutoff. In 1932, the D&RGW secured financing through the United States government, and Cutoff construction began in November. On June 15, 1934, just a few months ahead of the two-year deadline, the route was complete and was really when the modern Rio Grande system mainline was completed.

The train proceeded down the Dotsero Cutoff with our next stop at Bond then we followed the Colorado River, where the tracks switch sides of the river back and forth on the way to Dotsero. Since no one was sharing the vestibule with me, every time the train crossed the river, I just crossed to the other side of the vestibule, thereby putting me on the river's side. We passed the siding at Dell, met a freight train at Range and travelled through Red Rock Canyon passing several deer along the way. Just before Dotsero, we ducked under Interstate 70 and arrived at the junction with the line to Pueblo via Tennessee Pass. Proceeding again due west, we started our passage through Glenwood Canyon, where the railroad and the two-lane highway with the river in between its extremely high walls, made for a very narrow passage. It had been announced that the Interstate was going to be put through the canyon, but at this point, I was not sure how it would be done without destroying the canyon's beauty. As we made our way through the canyon, I stared into the beauty of it all - the river, the train, the highway and those walls and the vista left an image in my mind that I will never forget.

As the train arrived at Glenwood Springs, the vestibule that I was in filled with passengers ready to detrain and I also detrained for some fresh Rocky Mountain air. The platform swelled with the masses and I walked to the front of the Rio Grande Zephyr to see the vintage motive power then as our arrival was fifteen minutes ahead of schedule, I was in no hurry to return to the near-empty train which now had plenty of available dome seats. I chose one in "Silver Sky" which provided a view overlooking the train and it seemed as though the rest of the passengers were now riding in the other domes as well.

Emerging from a short canyon west of Glenwood Springs, the train sprinted across the agricultural Grand Valley, with its cliffs and mesas seeming to be steps leading to the sky. Running at track speed, we stopped at Rifle, which was founded in 1882 by Abram Maxfield and incorporated in 1905 along Rifle Creek, near its mouth on the Colorado; the community takes its name from the creek. We then entered De Beque Canyon and passed through it quickly, arriving at Grand Junction twelve minutes early, although no one boarded and twenty-six people detrained, leaving a mere thirty-four aboard. While the train was being serviced, I visited the Rio Grande Company Store in the depot, purchasing a Rio Grande hat before returning to "Silver Pine" and stored my other hat in my suitcase. I returned to "Silver Sky" with several passengers inviting me into the lounge under the dome for a round of beers and we discussed trains as we departed.

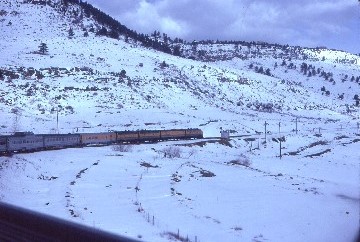

The Rio Grande Zephyr sped through the western end of the Grand Valley and near Fruita, we all returned to the dome, passed through a tunnel and rejoined the mighty Colorado River before I set eyes upon the incredible Ruby Canyon. It was love at first sight with the high mesa-like cliffs with their multitude of colours and shapes, the wide curving river and of course the train, but most importantly no roads, just a few ranches. The train was a small piece in the grandeur of it all and it was one of the completely unspoiled places on Earth. From my dome seat, I stared up along the canyon walls to the sky, thinking about how God had made all of this. A line on the cliff marked the train's passage into Utah and after a few more miles, the journey through Ruby Canyon was over and we left the Colorado River at Westwater to proceed into the Utah desert. The Book Cliffs came into view and would be on the right on the far side of the desert all the way to Helper. There were several reverse curves which allowed the train to gain altitude from the Colorado River to the watershed divide with the Green River, which was the racetrack of the Rio Grande as it reaches its maximum track speed across the desert. Thompson was passed at high speed since no one flagged the train today and this area was a wasteland in the true sense, a place where you can see the erosion caused by time.

Continuing our late afternoon desert trek, we came to Solitude Siding, which was a perfect name. Leaving Solitude to the wind, the Zephyr approached the next flag stop of Green River and flew through it onto the bridge over the river, the lowest point on today's trip, then started to climb towards Soldier Summit over eighty-five miles away. The Zephyr continued westward, passing the sidings at Sphinx, Desert, Vista and Woodside, then once past the west switch at Grassy, turned left to gain more elevation. At this point, the sun was beginning to set and the sky turned a bright red, giving the stainless steel of our train a reddish hue. The route was twisting to gain more elevation and joined the Price River for its climb to Soldier Summit, ascending the east flank of Utah's Wasatch Mountains to enter coal country, since coal from here was sent to Southern California for both export and domestic uses. We passed a coal facility at Wash where the mined coal is rinsed and this is where the Rio Grande had a branch to Sunnyside, a major coal-producing region which shipped coal trains to Kaiser Steel in Fontana, California and US Steel in Geneva, among others. Further west at Helper, the Utah Railway served mines south of town and we passed a string of loaded coal cars.

The train passed through Price as the sun showed its last rays of the day and we stopped on time at Helper, where a final crew change occurred and the four of us in "Silver Sky" decided it was time for dinner so we made our way to "Silver Banquet". While the tables had looked very impressive at breakfast, the dining car crew really out did themselves for dinner. The steward brought us our menus and while our unanimous choice was the Rocky Mountain Trout, they were out of that item at this late hour, so we all ordered Baked Young Turkey. The waiter returned with a bowl of consommé soup and a bottle of California White Zinfandel wine to have with my meal. As we discussed our day and the topic turned to our favourite portion of the route, I chose Ruby Canyon, then our dinners were served with whipped potatoes and broccoli florets. We departed Helper, passed the junction with the Utah Railway, then went through Castle Gate and Kyunne while enjoying our meal.

We returned "Silver Sky" first for a nightcap, followed by a toast to the Rio Grande Zephyr and its memory then went upstairs into the dome for the rest of the journey under the stars of night. The only lights seen were from those few passing cars on US Highway 6 before we returned to the shadows of the canyon where the only light there were the twinkling stars overhead. We reached the summit of Soldier Summit and started our westward descent, twisting and turning down the west side and the train's headlight illuminating the route. The highway was down below taking the shorter way along the valley floor then we negotiated the upper Gilluly Loop, making a 180 degree turn as the moon rose and shone brightly over the Wasatch Mountains while we descended the middle level. At the bottom, another 180 degree turn was negotiated before ducking under the highway bridge to continue our descent. Conversations turned silent as we all listened to the sound of the train in the night, whistling for a crossing and its sound echoing off the canyon walls. There was no better place to ride a train at night than in the top of a dome car; a truly fantastic experience.

We went by a group of lights and someone said that was Thistle, a small town at the junction of the canyons with a Rio Grande branch diverging for Marysville. Thistle was forever changed less than two weeks later since on the night of April 14th, 1983, right after the westbound Rio Grande Zephyr had passed through, the unstable mountain just to the west of Thistle slid down into the valley, covering the Rio Grande Railroad and the highways into town. Since it had been a very wet winter season, the blockage of the natural drainage caused a flood to engulf the valley behind the natural dam and flooded Thistle. Houses were literally floated to the eastern shore of the new lake and the Rio Grande Zephyr was trapped to the west of the slide and returned to Denver on the next day via the Union Pacific across Wyoming. The Rio Grande Zephyr then finished its career running to and from Grand Junction with a bus connection to points west. The railroad's only recourse was to run its trains over Union Pacific and began drilling tunnels through the adjacent mountain, along with a new route above where Thistle once had been. On July 16th, 1983, eighty-three days after the last run of the Rio Grande Zephyr, the first Amtrak train, The California Zephyr, travelled the new Thistle line and plunged into the first of the twin bores to be completed.

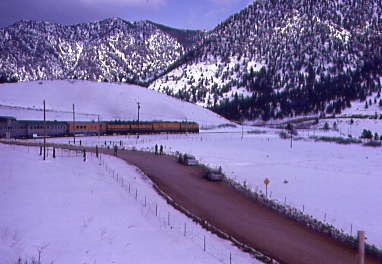

The train sped through the narrows and burst out into the valley to Provo and it was a sea of lights ahead as we proceeded into their brightness. In twenty minutes, we arrived at Provo, our penultimate stop and while at the station, I walked back to "Silver Banquet" to thank the entire crew for the excellent meals and received a complete set of Denver and Rio Grande Western dining car menus. With my Rio Grande experience almost complete, we passed the bright lights of the US Steel Mill at Geneva on the right and Utah Lake on the left then followed Jordan River through a narrow passage into the southern end of the Salt Lake Valley and its increasing lights as we continued north. We were traveling at track speed but slowed for Roper Yard, Rio Grande's main Salt Lake City facility, before entering an industrial area then travelled down the middle South Rio Grande Street very slowly and arrived at Salt Lake City station ten minutes early.

My Rio Grande experience was over and I walked from the dome of "Silver Sky", thanked the lounge attendant for his excellent service and returned to "Silver Pine" to collect my bags then stepped off this magnificent train and just stared at the glory of it all. I took one last hard look, then turned and walked away.

The Pioneer 25 3/28/1983I walked through the station and one of the "Silver Sky" four offered me a ride to the Amtrak station, which I accepted, and within five minutes, I was at the Union Pacific station awaiting the Pioneer. I was the only passenger from the Rio Grande Zephyr to be travelling by rail since all other passengers opted for the van to Ogden. While waiting, I noticed the murals of the Promontory Meeting of the Builders of the Transcontinental Railroad on the walls then boarded the Pioneer for an on-time departure. We crept through Union Pacific's North Yard and piggyback facility then picked up speed as we ducked underneath Interstate 15 and paralleled the roadway along the western face of the Wasatch Mountains. My Amfleet coach had a slight rattle to it as we continued north on Union Pacific's double track main line. While in total darkness, off to the left was the Great Salt Lake and to the right were the snow- capped peaks of the Wasatch Mountains. We slowed for the curve around the wye into Ogden Union Station, where the City of San Francisco was waiting to hand off their passengers bound for the Northwest.

3/30/1983 After ten minutes of station work, we were off into the Utah night onto more new trackage and I dozed off and on for the next forty minutes until the next stop at Brigham City. A family boarded and sat in front of me and talked for the next hour. As I knew Bear River Canyon was close, I walked back to the sleeper and opened the vestibule to enjoy the night-time air then the conductor arrived, expecting to find me somewhere nice and quiet. The train slowed to ten miles an hour for the curved bridge above the Cutler Reservoir and entered a tunnel high on the ledge above, which made for a great night-time experience. I closed the vestibule and returned to the now-quiet coach and went back to sleep all the way to outside Pocatello, crossing into the state of Idaho as I dreamt, then a gentle nudge from the conductor woke me up and he informed me we would be in Pocatello in five minutes. We entered Union Pacific's large hump yard, passed eastbound freights waiting their turns at the main line to points east and south before overtaking a westbound freight and entering town for a crew change and inspection.

We arrived at Pocatello's handsome red brick depot on time and I stepped off the train for the first time in Idaho, and was greeted by my brother Bruce in his Amtrak uniform. He performed his station work and on his lunch break (2:30 AM), he drove me to his home to start my five-day visit with he and my sister-in-law Karla. Since I had arrived by rail, he did not have to drive down to Ogden to pick me up and it was the end of a perfect day as I lay on a king-sized waterbed to sleep.

The Bus 4/3/1983To save Bruce a drive to Ogden, I decided to take Greyhound, which followed US Highway 91 via Preston, Idaho and Logan, Utah, far off the interstate that Bruce always took me on and the route was through basically the same countryside that the train passed during the night. It was a good trip, but made me realize why I enjoy the train so much, the main reason being freedom to move about. Also, bus passengers are a different breed of people than train riders. I arrived at Ogden's bus station then had no alternative to walking down the two worst blocks with many undesirable characters.

The Desert Wind 35 4/4/1983

Arriving early at Ogden Union Station gave me an opportunity to explore so counted how many platforms there used to be by the remaining cement slabs and inside were photographs of it during its glory days. My train, the Desert Wind, was sitting on Track 2 awaiting departure time then thirty minutes beforehand, the conductor led the passengers out to board the train while we waited for the thirty-five minute late City of San Francisco to arrive. That train only grew later as the Pioneer arrived on Track 1. Finally, fifty-two minutes late, the City of San Francisco arrived on Track 3 and was pulled by two freight locomotives as one of the Amtrak engines was dead. The passengers quickly transferred to their trains and we were first to depart Ogden forty minutes late.

The coach lights stayed on all the way past Salt Lake City and kept us awake, then the conductor did not collect any tickets until after Salt Lake City, so anyone travelling from Ogden to there received a free ride. The lights finally were turned off and I fell asleep across two Amfleet coach seats.

Awakening much later, I found the train in Meadow Valley Wash as we were now in Nevada on the way to Las Vegas. The Amfleet window were too small to do the scenery justice, although the route was becoming familiar as I had travelled it sufficiently and I instinctively began to know where the scenic highlights were. By Las Vegas, we had made up all of the lateness of last night so it was a nice treat to step off the train into the dry Nevada morning air. We departed on the advertised schedule and made our way to California on Union Pacific's mainline then after the line in Amcafé car disappeared, I went and ordered lunch, which was a far cry from what I had experienced on the Rio Grande Zephyr. That brought me back to the reality of Amtrak train travel in coach.

I read the newest issue of Trains Magazine but stopped to enjoy the passage through Afton Canyon then resumed reading and before I knew it, we were passing through the yard at Yermo. Ten minutes later, we were back on the double track main line of the Santa Fe at Daggett for the quick journey to Barstow, then it was on Victorville, where we passed many freight trains along the way before we climbed the east slope of Cajon Pass. Emerging from the cut at Summit, the air below had the brown Southern California smog. It was a speedy journey down the west side of Cajon Pass and we arrived at San Bernardino on time, then the Desert Wind sped down the Second District to Pomona, where I detrained, thereby saving me from having to go into Los Angeles then to Santa Ana. My parents drove out here to pick me then a forty minute drive home, where I be for two weeks before the next segment of this All Aboard America fare.

4/15/1983 Jeff Hartmann, my good and dear friend and I took our first overnight trip on the Sunset Limited to Phoenix to visit my brother Duane, his wife Lisa and their new daughter Stephanie.

Duane's friend Steve Fredson took us to McCormack-Stillman Railroad Park in Scottsdale and to Tucson to see some trains before we overnighted.

On April 16, 1983, we rode the Sunset Limited from Phoenix and arrived in Pomona the next day, where Jeff's father picked us up and took us home, after which I went to work.

| RETURN TO THE MAIN PAGE |