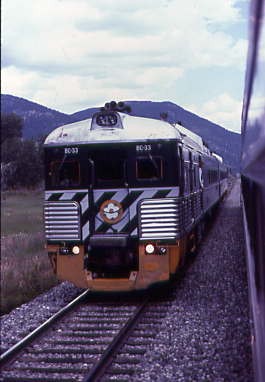

Canada's national rail service, VIA Rail, was created in 1978 by the Canadian government in response to Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian National Railway exiting the passenger business. However British Columbia Railway is a separate entity, as it is a provincial freight and passenger service, rather than national. BC Rail's passenger trains run with Rail Diesel Cars normally daily, to Lillooet and tri-weekly to Prince George. However, because of Expo 86, the World's Fair, which was held in Vancouver, the Cariboo Dayliner ran daily to Prince George all summer.

Pacific Great Eastern Railway/BC Rail backgroundThe Pacific Great Eastern Railway (PGE) was incorporated on February 27, 1912, to build a line from Vancouver north to a connection with the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (GTP) at Prince George. Although independent from the GTP, the PGE had agreed that the GTP, whose western terminus was at the remote northern port of Prince Rupert, could use their line to gain access to Vancouver. The railway was given its name due to a loose association with England's Great Eastern Railway. Its financial backers were Timothy Foley, Patrick Welch and John Stewart, whose construction firm of Foley, Welch and Stewart was among the leading railway contractors in North America.

Upon incorporation, the PGE took over the Howe Sound and Northern Railway, which at that point had built nine miles of track north of Squamish. The British Columbia government gave the railway a guarantee of principal and four percent interest (later increased to 4.5 percent to make the bonds saleable) on the construction bonds of the railway. By 1915, the line was opened from Squamish 176 miles north to Chasm. The railway was starting to run out of money, however. In 1915 it failed to make an interest payment on its bonds, obliging the provincial government to make good on its bond guarantee.

In the 1916 provincial election campaign, the Liberal Party alleged that some of the money advanced to the railway for bond guarantee payments had instead gone into Conservative Party campaign funds. In the election, the Conservatives, who had won 40 of 42 seats in the legislature in the 1912 election, lost to the Liberals. The Liberals then took Foley, Welch and Stewart to court to recover $5 million of allegedly unaccounted funds. In early 1918, the railway's backers agreed to pay the government $1.1 million and turn the railway over to the government.

When the government took over the railway, two separate sections of trackage had been completed: a small 20 mile section between North Vancouver and Horseshoe Bay, and one between Squamish and Clinton. By 1921, the provincial government had extended the railway to a point 15 miles north of Quesnel, still 80 miles south of a connection to Prince George, but it was not extended further. The track north of Quesnel was later removed. Construction of the line between Horseshoe Bay and Squamish was given a low priority because there was already a barge in operation between Squamish and Vancouver, and the railway wanted to discontinue operations on the North Vancouver-Horseshoe Bay line. However, the railway had an agreement with the municipality of West Vancouver to provide passenger service that it was unable to get out of until 1928, when they paid the city $140,000 in support of its road-building programme. The last trains on the line ran on November 29, 1928, and the line fell into disuse, but was never formally abandoned.

For the next twenty years, the railway would run from "nowhere to nowhere". It did not connect with any other railway and there were no large urban centres on its route. It existed mainly to connect logging and mining operations in the British Columbia Interior with the coastal town of Squamish, where resources could then be transported by sea. The government still intended for the railway to reach Prince George, but the resources to do so were not available, especially during the Great Depression and World War II. The unfortunate state of the railway caused it to be given nicknames such as "Province's Great Expense", "Prince George Eventually", "Past God's Endurance", "Please Go Easy" and "Puff, Grunt and Expire".

Starting in 1949, the Pacific Great Eastern began to expand. Track was laid north of Quesnel to a junction with the Canadian National Railway at Prince George. That line opened on November 1, 1952. Between 1953 and 1956, the PGE constructed a line between Squamish and North Vancouver. The PGE used their former right-of-way between North Vancouver and Horseshoe Bay, to the dismay of some residents of West Vancouver who, mistakenly believing the line was abandoned, had encroached on it. The line opened on August 27, 1956. By 1958, the PGE had reached north from Prince George to Fort St. John and to Dawson Creek where it met the Northern Alberta Railways.

In 1958, Premier of British Columbia W.A.C. Bennett boasted that he would extend the railway to the Yukon and Alaska, and further extension of the railway was undertaken in the 1960s. A 23 mile spur was constructed to Mackenzie in 1966 and a third line was extended west from the mainline (somewhat north of Prince George) to Fort St. James, which was completed on August 1, 1968. The largest construction undertaken in the 1960's was to extend the mainline from Fort St. John 250 miles north to Fort Nelson, less than 100 miles away from the Yukon. The Fort Nelson Subdivision was opened by Premier Bennett on September 10, 1971 but unfortunately, the opening of the line was overshadowed by the inaugural train derailing south of Williams Lake, south of Prince George.

The railway underwent two changes of name during this time period. In 1972, the railway's name was changed to the British Columbia Railway (BCR). In 1984, the BCR was restructured and under the new organization, BC Rail Ltd. was formed, owned jointly by the British Columbia Railway Company (BCRC) and by a BCRC subsidiary, BCR Properties Ltd. The rail operations became known as BC Rail.

Cariboo DaylinerThe railway's RDCs were self-propelled and powered by two 300 horsepower Cummins diesel engines. They could be operated singly, but were almost always coupled in two or four car trains. There were two classes of service - First Class, or Cariboo Service, which had more luxurious seating and meals at no additional charge, or Regular Coach seating. The Cariboo Class RDCs were RDC-4s with a baggage compartment, galley and the Cariboo seating. Due to the rural nature of the route, the train made any necessary stop at any time to deliver groceries, mail, newspapers and other items. The 461 mile journey takes 13.5 hours, but because of the summer sun in the northern latitudes, the trip will be in complete daylight.

I always wanted to ride an RDC after seeing them travel between South Edmonton and Calgary, Alberta during family vacations. I walked out of the BC Rail station to these 1950's Budd Company product and gazed at them before

boarding. My friend, Jeff Hartmann, who was travelling with my parents and I on this vacation to Vancouver, and I found a pair of seats. As we had twenty minutes before departure, we explored the trainset of four RDCs coupled and

duly noted that our Cariboo Class car had superior seats and more leg room than the regular coaches, whose seats were close together. Their interiors were not as colourful or as nice as ours, but were functional for the service

they provided.

Our train at the North Vancouver station, after which we returned to our seats and waited for departure on this single-track line, with no signals, as all was done by track warrant control. Departure was on schedule and we passed through the BC Rail yards and the Royal Hudson steam train being readied for the run to Squamish. Once at the west end of the yard, we passed under the Lions Gate Bridge and below it was where I once photographed this train years ago.

Breakfast was served which was a waffle with the most delicious sausage. We then crossed the Capilano River and proceeded through the heavily-urbanized District of West Vancouver, literally passing through the residents' properties, some of the most expensive in all Canada, and had already been slowly climbing to the 4,500 foot Horseshoe Bay tunnel at Milepost 11.3, one of the longest on the railway. We stopped at the end of Horseshoe Bay siding to wait for a long BC Rail freight train with two locomotive on the point and three radio-controlled units buried mid-train. Operating trains in this fashion minimized the need for helper districts over the undulating profile. We reversed out of the siding onto the mainline then passed high above the community and ferry docks of Horseshoe Bay.

Our route returned to water level as we rolled along Howe Sound. Jeff and I walked back to the vestibule of the rear RDC so we could better enjoy the scenery, passing the islands in the Sound with the Coast Mountains rising behind. To our right, the Sea-to-Sky Highway, BC Highway 99, was backed by the sheer cliffs and most of the peaks on both sides were in excess of 6,000 feet and heavily forested. The Sound and the mountains were extremely beautiful with the train reflecting as we passed the still waters.

We passed Porteau Cove Provincial Park then at Porteau, MP 26.0, met BCOL 753 South and continued along the shore to Britannia Beach, where there was a small harbour. As I looked to the head of the Sound, I saw the 8,787 foot Mount Garibaldi looming high above the surrounding peaks as the train twisted along the shore. On the right was the monolith Stawamus Chief, said to be the second largest rock in the world and we could see climbers on its face, which loomed 2,000 feet above the train. We arrived at the northern end of Howe Sound and stopped at Squamish, home of the BC Rail locomotive and maintenance shops.

Departing Squamish, the train started to ascend a 2.2 percent grade, the steepest on the entire railway, and we were following the Cheekeye River into the Coast Range by the way of Cheakamus Canyon.

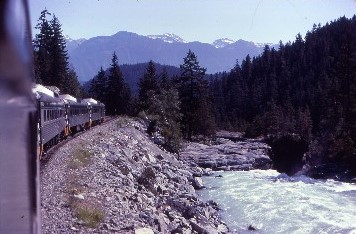

Later our train passing through Cheakamus at MP 50.0.

Climbing above Cheakamus.

The view after we crossed the bridge at Swift, MP 55.1.

Alpha Mountain at an elevation of 7,552 feet and Omega Mountain, 6,292 feet.

The train twisted and turned on its way up the narrow rocky gorge. The ride in the vestibule was incredible and the conductor came back to see how we were enjoying the ride, noting my camera. We crossed the bridge on which the RDCs were pictured on a Pacific Great Eastern timetable and it was that picture that drew me to this railway, and at this moment, I was crossing that bridge. It was an incredible feeling to live out one of my life's dreams.

We passed by Brandywine Falls, the name of which is believed to have come from a wager between two surveyors (Jack Nelson and Bob Mollison) for the Howe Sound and Northern Railway over the height of the Falls, the closest guess winning a bottle of brandy (wine). The height was measured with a chain and it was Mollison who won the bottle of brandy and Nelson then named the falls Brandywine. After passing through the canyon, we stopped at Whistler, a world- renowned ski resort which had recently launched a Southern California advertising campaign.

Alta Lake near Whistler. BC Rail offers an excellent way to reach here from Vancouver, which is just an airport away from the rest of the world. Here we were at the summit of the Coast Range and descending from Alta Lake, we twisted and turned down into the Pemberton Valley, a very fertile part of the province.

The train climbing near Green River, MP 88.5.

Near Tisdall, MP 90.4.

BCOL SD40-2 754 at Pemberton on a helper set.

A view of the Pemberton Valley. At Pemberton, we dropped off Vancouver newspapers for the local townsfolk and crossed the Lillooet River sixty miles from the District with the same name. The Lillooet River flows southeast out of the Coast Range and joins the Fraser River near Chilliwack. From Pemberton it was another climb, this one up to Birken, the summit of the Cascade Range and one of the last helper districts on the railway.

Green Lake. The mountain peaks were some of the most beautiful and seldom seen, something I did not expect to see.

Mount Currie, 8,500 feet at MP 99.4. From Birken, MP 112.6, we descended the grade to D'Arcy.

Birkenhead Lake.

D'Arcy, MP 122.9 and the south end of Anderson Lake.

We travelled along Anderson Lake which had a depth of 700 feet for the next fifteen miles.

Anderson Lake, west of Lillooet, is drained by the Seton River, which, along with the Fraser River, feeds Seton Lake. Anderson Lake used to be the same water body as Seton Lake, but a landslide from the Caoyosh Range divided the lakes thousands of years ago.

By coincidence, this was the day that BC Rail hired a helicopter to film their passenger service. We plunged into a short tunnel and there was a helicopter photographing our train before flying in front of us as we passed and it was really interesting to watch the pilot manoeuver his aircraft and the whole event was entertaining. This glaciated valley is in a "U" shape and we crossed the remains of the landslide before we started to parallel Seton Lake then entered a 2,940 foot tunnel at MP 125.6 and emerged hugging the shoreline of Seton Lake, which had a milky blue-green colour to it and with our shore running, the helicopter continued to photograph us.

I wished I could obtain a copy of that film to show people the beauty through which this train runs, and I was in the middle of it in the vestibule right. To the left was Mount McLean and across the lake was the Cayoosh Range. We passed the community of Shalath, from which BC Rail ran a school train to Lillooet from 1979 to 2002, which the children named "Budd Wiser". Seton Lake was as deep as Anderson Lake and BC Rail has had several derailments, putting locomotives into the lake followed by a very costly savage operation to retrieve them and in a few cases, rebuild them.

Our passage along Seton Lake. At the north end of the lake, we passed the Seton Canal, a diversion of the flow of the Seton River from Seton Dam, just below the flow of Seton Lake, to the Seton Powerhouse on the Fraser River at Lillooet. The canal bridges Cayoosh Creek 984 feet below its commencement and is about 2.17 miles in length, ending just below a bridge used by the Texas Creek Road, where the canal's waterflow is fed into tunnels which feed the Seton Powerhouse on the farther side of a small rocky hill. Most of the water carried by the canal is the volume of the diverted Bridge River, which is fed into Seton Lake via BC Hydro's Bridge River generating stations at Shalalth, which are supplied by diversion tunnels through Mission Ridge from Carpenter Lake, the reservoir created by Terzaghi Dam. There is also a fish ladder so the salmon can return to spawn.

The train ran the last miles to the division point between the Squamish Subdivision and Lillooet Subdivision at Lillooet, MP 157.6.

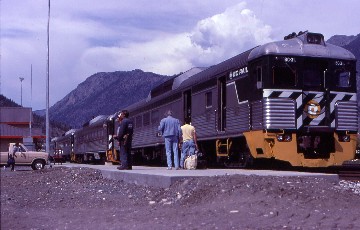

Lillooet was a twenty minute stop. The town began as a goldrush centre in the late 1850's, booming during the progression of discoveries on the Fraser and in the Cariboo in the early 1860's. The title of "the largest town west of Chicago and north of San Francisco" moved in rapid succession from Yale to Lillooet and then to Barkerville. Just after this gold rush, the town's layout was surveyed by the Royal Engineers. The economy was historically based upon logging, the railway, ranching, farming and government services. The long growing season has favoured orchards, and in recent times, ginseng. Once, hop and tobacco crops supported the former local beer, cigar and chewing tobacco industries, although it has relied upon forestry since the mid-1970's.

The northward advance of the Pacific Great Eastern Railway railhead reached the head of Seton Lake in January 1915 and the Lillooet locality the following month. PGE built a depot between the Seton River and Cayoosh Creek and also in February 1915, the first passenger train arrived, triggering a revival for the isolated town, since a railway could ship agricultural produce. By year end, the track reached Clinton, an additional 45 miles north.

To benefit the railway rather than land speculators, PGE bypassed the downtown by crossing the Fraser south of the Seton River on the Lillooet railway bridge. PGE erected a station and four-stall roundhouse at East Lillooet, which was a divisional point. The initial depot, called Lillooet station, was one-and-a-half miles westward across the Fraser. In 1930, the railway built the 5.5 mile Lillooet Diversion from the head of Seton Lake, through the downtown and north to the Polley bridge. In 1931, PGE completed the bridge, built a new two-storey station downtown, and dismantled and reassembled the roundhouse nearby; the latter was demolished during the early 1970s.

The last two RDCs were cut off so they could return to North Vancouver in about two hours with the train from Prince George.

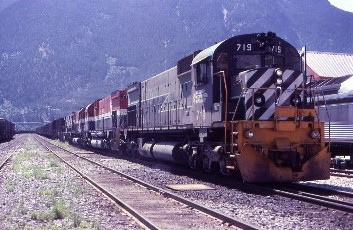

While it is surrounded by mountains, the temperatures can reach 100 degrees in the summer, but today it was only in the mid-80's. Also here was BCOL M-630 719, built by Montreal Locomotive Works in 1972. It was retired in 1990 and went to Mexico with several others of this model, becoming Ferrocarriles Nacionales de México 719, then scrapped in the late 1990's.

We changed crews here then departed north.

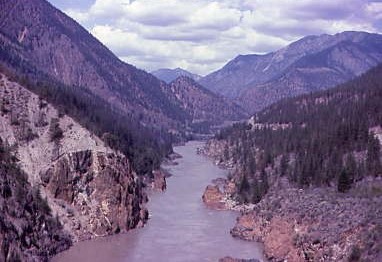

Crossing the Fraser River on the 820 foot long Polley Bridge with the tracks over 200 feet above the river.

I enjoyed all this from new location in the new rear vestibule.

Climbing out of Fraser River canyon near Polley, MP 160.3.

Continuing the climb out of the canyon near Fountain, MP 165.3, during which we would ascend 3,000 feet over the next thirty miles to gain access to the Cariboo Plateau, a volcanic plateau in south-central British Columbia. It is part of the Fraser Plateau which is a northward extension of the North American Plateau. Its southern limit is the Bonaparte River although some definitions include the Bonaparte Plateau between that river and the Thompson, but it properly is a subdivision of the Thompson Plateau. The portion of the Fraser Plateau west of the Fraser River is properly known as the Chilcotin Plateau, but is often mistakenly considered to be part of the Cariboo Plateau, which is east of the Fraser.

As a region and historical identity, the Cariboo is sometimes considered to extend to the Thompson River to the south of that, and to border on the city of Kamloops at its southeastern corner and even as far as Lytton, at the confluence of the Fraser and Thompson Rivers. The District of Lillooet is generally considered to be in the Cariboo, while the Bridge River Country to its west was sometimes referred to as the West Cariboo, as were also the ranches along the west side of the Fraser northwards towards the Gang Ranch. Broader meanings of "the Cariboo" sometimes include the Chilcotin, west of the Fraser. The geographic region known as the Quesnel Highland, which forms a mountainous series of foothills between the plateau proper and the Cariboo Mountains, is likewise considered to be part of the Cariboo in a cultural-historical sense – not the least because it is the location of the famous Cariboo goldfields and the one-time economic capital of the Interior of British Columbia, Barkerville.

The Cariboo is commonly divided into North Cariboo, Central Cariboo and South Cariboo. The commercial centre of the north is Quesnel, of the central Williams Lake and of the south 100 Mile House. The Cariboo region is generally considered to reach as far southeast as the city of Kamloops and to include the Cache Creek and Lillooet areas in the south. The region west of the Fraser River north of Lillooet, the Chilcotin, is often considered to be a part of the Cariboo; the country south of it immediately west of Lillooet is sometimes referred to as the West Cariboo.

The name is a reference to the caribou that were once abundant in the region and was the first region of the interior north of the lower Fraser River and its canyon to be settled by non-indigenous people, and played an important part in the early history of the colony and province. The Cariboo goldfields are underpopulated today but were once the most settled and most significant of the regions of interior British Columbia. As settlement spread southwards of this area, flanking the route of the Cariboo Road and spreading out through the rolling plateaus and benchlands of the Cariboo Plateau and lands adjoining it along the Fraser and Thompson rivers, the meaning changed to include a wider area than just the goldfields.

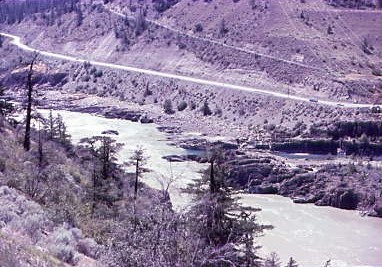

The rails hugged the east wall of the canyon as the RDC twisted and turned to gain elevation. Across the river it was odd to see irrigated fields but I learnt that the medicinal plant and herbal remedy, ginseng, was grown here. The view was spectacular as we continued to climb and was similar to view from an aeroplane. We came to Pavilion at MP 177.9, where we passed a freight train waiting in the siding and I was really impressed how BC Rail runs their railway.

Climbing up to Moran, MP 181.0, the tracks were now over 2,500 feet above the Fraser River and at this point, we diverged from it and would not see the river again until Prince George.

At Kelly Lake, MP 192.6, we went into the siding.

The meet with Train 2 from Prince George, our southbound counterpart, after which I returned to my seat to change film, then wondering if it would be possible to ride in the front of the RDC with the engineer, I walked through the galley and the baggage compartment into the control area, where I was greeted warmly and offered the fireman's seat. I accepted that and was told they would arrange for me to stay here all the way to Prince George and I was naturally in heaven.

An example of the forward view from the fireman's seat, an incredible experience.

A trestle at Fill, MP 211.7. When we passed MP 215, the engineer pointed out a deep canyon, informing me this was called Chasm.

As we sped along, we went through Lone Butte and passed the old water tower which still stood. Just before Horse Lake, we passed the highest elevation on the railway at 3,864 feet, then with Highway 97 very close to the tracks, a log truck cut in front of our train and for the next five minutes, the dangers of railroading were discussed. My engineer had had a lot of close calls but never hit anything. I told a few San Diegan stories and he was very glad that he worked in British Columbia away from all of the lunatics in Southern California; his points were well taken. We discussed wildlife and there was large variety seen here in the Cariboo. The conversation then turned to winter railroading and he ensured me that operating RDCs in winter takes a little more concentration but is fun year-round.

We then arrived at Exeter, MP 259.5, in the village of 100 Mile House. It was originally known as Bridge Creek House, named after the creek running through the area and its origins as a settlement go back to when Thomas Miller owned a collection of ramshackle buildings serving the traffic of the gold rush as a resting point for travellers moving between Kamloops and Fort Alexandria, 98 miles north of 100 Mile House farther along the Hudson's Bay Brigade Trail. It acquired its current name during the Cariboo Gold Rush where a roadhouse was constructed in 1862 at the 100 miles mark up the Old Cariboo Road from Lillooet.

In 1930, Lord Martin Cecil left England to come to 100 Mile House and manage the estate owned by his father, the 5th Marquess of Exeter. The estate's train stop on the Pacific Great Eastern railway was to the west of town and at that time, the town consisted of the roadhouse, a general store, a post office, telegraph office and a power plant and had a population of 12. The original roadhouse burned down in 1937.

It was a pleasant little village, typical of Cariboo communities. Leaving town, the engineer pointed out a herd of buffalo, something I did not expect to see in this part of British Columbia. We sped through the forest with the occasional patch of farm or ranch land and I learnt that cattle was an important business in Cariboo country which surprised me. We then stopped at one of the many flag stops, this one the Flying U, so passengers could detrain for the Chub Lake Guest Ranch.

BCOL 752 South at Lac La Hache, MP 273.4.

Lac La Hache. When a French Canadian fur trader dropped his axe into a remote Cariboo Lake while ice fishing, he most likely never would have suspected that he was making history. Its English translation is "Lake of the Axe" and has remained the name to represent this beautiful lakeshore destination. This area is rich in tales of fur traders, gold seekers and cattle ranchers. By the 1860's, gold fever was running high as miners searched for the jackpot first near Likely, and later at Barkerville. With teams of horses, mules and oxen, the fortune-seekers plodded north along the Cariboo Wagon Road skirting the eastern shores of the lake.

Both the Shuswap and Chilcotin First Nations inhabited the area. Long before the lure of wealth brought the fur traders west, the Shuswap Indians established pit houses near the present day village of Lac La Hache. The Chilcotins named the lake Kumatakwa, meaning Chief or Queen of the waters. The small, friendly community of Lac La Hache describes itself as the "Longest Town in the Cariboo". Highway 97 skirts the entire 11 mile shoreline of this beautiful lake in its rolling Fraser Plateau setting.

The scene at Onward, MP 305.8. Further on we passed the scenic and deep blue Williams Lake before arriving at the namesake City of Williams Lake, which is known as the cattle capital of British Columbia, as well as being a major lumber center.

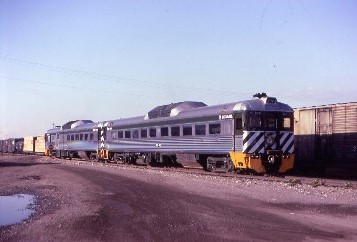

We arrived at South Williams Lake and I detrained to photograph our one-car train, RDC-3 BC-30, nee Pacific Great Eastern BC-30, built by Budd Company in 1956. When BCOL was taken over by Canadian National in 2002, BC-30 was sold to the Wilton Scenic Railroad in New Hampshire and operated there from 2003 to 2005, then it was sold to the Newport Dinner Train on the Newport and Narrangasett Railroad in Newport, Rhode Island.

South Williams Lake was a crew change point, the end of the Lillooet Subdivision and the beginning of the Prince George Division. My former engineer introduced me to the new one for the journey to Quesnel, who had the Canadian habit of adding "Eh" at the end of every sentence. Just as we were about to leave, a southbound freight train rolled by us, then we pulled up, stopped and threw the switch and departed. As we made our way out of the city, Williams Lake was larger than I expected.

The new engineer and I got to know each other and after chatting for twenty minutes, he advised me to be ready with my camera as we came out of a curve and made our way onto the Deep Creek Bridge over Hawks Creek, MP 330. At 312 feet high and over 1,200 feet long, this was the highest bridge in the British Empire when constructed in 1920 by the Canadian Bridge Company. It was the highest bridge that I had been over and was very glad not to be afraid of heights. Two words described the bridge and our crossing - totally awesome!

We passed Soda Creek, MP 335.5, where from 1863 to 1921, river steamers plied the Fraser River between here and Prince George; the railway was the latecomer to this area. The countryside was rolling and the train kept its schedule as we continued northward. The engineer gave me a rolling history lesson on this part of British Columbia and I because of such BC Rail crew friendliness, I learnt more today than on any other of my future trips.

The front view at Kersley, MP 371.6. Just before Quesnel, the engineer allowed me to look at his employee timetable and noticed that I was really interested in it. At Quesnel, MP 384.6, I returned it to him and thanked him for such an excellent trip here since there was going to be another crew change. Before he left, he told the new engineer not to leave until he returned then a few minutes later, he came back with a bag and told me to ride with him tomorrow southbound, shook my hand and off he went. I opened the bag and inside found five brand new BC Rail employee timetables. His kindness made my whole trip.

The British Columbia Railway, formerly Pacific Great Eastern station built in 1921. After seven laborious years of construction, much of it accomplished by men with shovels and picks, the Pacific Great Eastern Railway arrived in Quesnel on July 30, 1921, accompanied by much pomp and circumstance. While a railway in the Cariboo was first envisioned in 1891, construction did not actually begin until 1914. The railway operated as the PGE until 1956, when it was renamed the British Columbia Railway. Quesnel remained the northern terminus of the PGE until 1952, when a bridge built across the Cottonwood River allowed the railway to be completed to Prince George.

Long before the arrival of prospectors during the Cariboo Gold Rush of 1862, the First Nations peoples, the Dakelh or Southern Carrier, lived off the land around Quesnel, occupying the area from the Bowron Lakes in the east to the upper Blackwater River and Dean River in the west. The Southern Carrier Nation were known among themselves as ‘Uda Ukelh’, meaning ‘people who travel by boat on water early in the morning’.

The name "Quesnel" is derived from Jules-Maurice Quesnel, who accompanied Simon Fraser on his journey to the Pacific Ocean. Quesnel came to be called 'Quesnelle Mouth' to distinguish it from Quesnel Forks, 60 miles upriver. In 1870, it was shortened to Quesnelle and by 1900, it was spelled the way it is now. Quesnel is located along the gold mining trail known as the Cariboo Wagon Road and supplied nearby Barkerville, the commercial centre of the Cariboo Gold Rush. It also marks one end of the Alexander MacKenzie Heritage Trail. Because of its location on the Fraser River, it was also an important landing for sternwheelers from 1862 to 1886 and then, from 1909 until 1921. The last sternwheeler on the upper Fraser was Quesnel's own namesake craft, and home town product, the Quesnel.

The city known for its forestry, particularly the production of pulp and lumber and it is the single biggest employer, being home to a Bleached Chemi-ThermoMechanical Pulp mill that was built in 1981 and a northern bleached softwood kraft pulp mill that started production in 1972.

The new engineer introduced himself and noticed that I was ending all of my sentences with "Eh", then upon learning I was a native Californian, jokingly made me an honourary Canadian. Suddenly the radio came alive with chatter as the freight train we passed at Williams Lake derailed just south of Exeter with twelve cars on the ground. By the sound of it, it was quite bad with the dispatcher holding trains at both Williams Lake and Lillooet until the tracks were cleared. The engineer asked me when I was going back south and when I said tomorrow he remarked that I would most likely be bussed from Exeter to Lillooet. So much for my cab ride down the Fraser River canyon and grade into Lillooet, but I still had the rest of today's ride to enjoy.

We departed Quesnel on our final portion of the journey and had about a two hour ride ahead, passing rows of lumber plants this early evening but as we were so far north, would still reach Prince George in daylight. So far, the weather had been perfect with not a single cloud. On the outskirts of Quesnel along Highway 97 was a huge gold pan, pick and shovel, paying tribute to the local history.

After twenty minutes we crossed the Cottonwood River bridge, 234 feet above the river. This bridge was not completed until 1952 and was the final link in the Pacific Great Eastern between Quesnel and Prince George. Similar to the Deep Creek Bridge, this one was truly impressive at 1,023 feet in length and the shadows were covering the cuts as the sun started to set. My engineer then pointed out the Ahbua Creek Bridge, where a silver spike ceremony took place in 1952 with the joining of the rails and the completion of the railroad. We continued our trek through Cariboo Country, crossing minor bridges and rounding a few curves as we made really good time. The Fraser River was back on the west, escorting us into Prince George and we passed the lumber mills and went through BC Rail's yard prior to the arriving at the BC Rail station, MP 462.5, with me still in the fireman's seat. What a trip! I went back to the coach section to meet my parents and Jeff before we detrained and took a taxi to into Prince George since the station was on the south side of the city. We went to the Simon Fraser Hotel for a restful night.

Cariboo Dayliner BC Rail Train 2 7/21/1986

I was back in the fireman's seat as we departed Prince George and was glad I took pictures yesterday because we were basically proceeding into the sun. I was naturally was seeing the line from a different viewpoint and saw things I missed yesterday. The engineer and I discussed Barkerville, the famous gold rush town, along with Wells, where one can have a living feel of Cariboo history. The conversation soon turned to fishing and hunting then we crossed Cottonwood Creek high in the air without a single cloud in the sky and twenty minutes later, arrived at Quesnel and I thanked my engineer for a nice two days of riding with him.

We switched crews and I was greeted with "How did you like your present, eh?" and I responded "Fantastic, eh!" and off we went towards Williams Lake. Just south of Quesnel, we passed a northbound freight but it was just the cars from Williams Lake staying on their schedule and going north. My engineer reminded me that they had to keep freight moving on both sides of a derailment or money will be lost if the railway shuts down, then our conversation turned to BC Rail's future and the exporting of coal from the Tumbler Ridge line to Japan.

We continued our southbound trek and as we passed Alexandria, MP 358.1, I was told the story of Fort Alexandria. It was general area encompassing a trading post, ferry site and steamboat landing and its name honours Alexander Mackenzie, who in 1793 on his Peace River-to-Pacific Ocean expedition, was the first European to visit the Alexandria First Nation village. On being warned of the dangerous falls and rapids downstream, Mackenzie returned northward beyond the future Quesnel, before turning westward along the West Road River (Blackwater River) toward the coast.

In 1826, when the Chilcotin attacked this village opposite the fort, the fur traders supplied arms to the vulnerable defenders. This gesture caused the former to stop trading with the fort for a period. Although the Carrier conducted some revenge killings that year, hostilities between the two groups had subsided by the following year. In 1821, George McDougall of the North West Company Chala-Oo-Chick trading post, west of Fort George, paddled downriver to establish the Alexandria trading post, prior to the corporate merger with the Hudson's Bay Company that summer. I had no idea that the Hudson's Bay Company reached this far north before the roads and railways came and was very impressed how they opened up the whole wide expanse of the North.

We flew out onto the Deep Creek Bridge and in the bright sunshine of the day, it looked deeper than it did yesterday. It was then a quick run to Williams Lake and bid my engineer goodbye and thanked him for everything. He invited me to come back and that he enjoyed my visit.

Our two-car RDC at Williams Lake before I returned to the cab area and our new engineer climbed aboard. Off we went through Cariboo Country on 54.4 miles of steel rails until Exeter and the bus, making quick time.

The Bus 7/21/1986Jeff and I chose the front seat so we would have a forward view and I was able to strike up a conversation with the driver and he became a tour guide.

South of Exeter, we crossed over the tracks and came upon the derailment site. It was a mess with cars strung about the right-of-way and piled up and was an amazing sight. We headed away from the tracks on a nice two-lane highway which we stayed on until Cache Creek then turning west, the road twisted and turned to get up to the divide that leads to the Fraser River Canyon, which we crossed, and ten minutes later, were ducking under the BC Rail tracks. With the river on the right below and the tracks slightly above on the left, this arrangement continued until the tracks bridged us before they cross the Fraser River and further downstream, we crossed the river and arrived in Lillooet.

Cariboo Dayliner BC Rail 2 7/21/1986

We were all happy to be back on the friendly RDCs and we departed as I walked forward and was invited into the control area so I could enjoy the views of Anderson and Seton Lakes from my now-usual seat. At D'Arcy, Jeff found me and told me that they were going to start to serve dinner and that I had a seatmate. I went back and sat with a very attractive woman named Selah, who was travelling from Lillooet to Squamish. The attendant bought us our meal of white salmon, steamed round potatoes along with a roll and soft drink. We enjoyed our salmon and I remarked that I had never heard of white salmon before, much less eaten it. Selah gave me more than the necessary lesson about types of salmon, breeding practices and their run to spawn, after which I knew more about salmon than I ever wanted.

I showed Selah the view from the front of the train and she was amazed, saying that she had ridden this train over twenty times and never saw this view before. We arrived at Squamish and Selah detrained into the night and we waved goodbye to each other. I walked back up to the front and watched as the train skirted Howe Sound, knowing my first Canadian train ride was almost over. The sun began it long slow set as we curved above Horseshoe Bay and into the tunnel prior to rolling through West Vancouver, then passed under the Lions Gate bridge, through the BC Rail yards and into North Vancouver station ten minutes early, thus ending a most wonderful two-day adventure. The four of us drove back to Tsawwassen and spent two more nights there.

| RETURN TO THE MAIN PAGE |