|

|

| This 1923 aerial

view shows an RV train, probably with #11 steaming,

switching the Wright Chemical Company on the wye at

Branch Junction in Union. The road cutting across the

image is Chester Road, much later the busy Route 22.

Union Township Historical

Society. | |

“Even World War I failed to help

stabilize the little Rahway, although business picked up

considerably" (

Cunningham 38

). The Rahway Valley

Railroad spiraled into a cataclysmic nose-dive in the years

immediately after World War I. War time plants reduced production,

changed output, closed down, or left the area altogether. Activity

along the rails of the RV went from boom to bust literally

overnight. “No one knows just how the road got through the tough

years that followed” (Young).

"Hardly had the management finished searching

their safe with candles to see if there might possibly be something

left in it when the famous ice storm of the winter of 1918-1919

struck in with devastating effects” (Young).

The lack of business being done along t

he line set the railroad up for a record setting

deficit in 1920, expenses eclipsed revenues by more than $50,000.

James S. Caldwell, the railroad’s General Manager,

and Andrew A. Lockwood, the railroad’s Auditor,

attempted to straighten out the railroad’s books but it continued to

sink further into debt with each succeeding year. “All through

the Twenties little kept the line going save its score of fuel and

lumber yards. Outside income consisted of infrequent Jersey Central

specials which crept over the uncertain trackage . . .”

(Young).

The Elmira interests who

held the majority of the railroad’s debt looked to rid themselves of

the financial monstrosity. Matthias H. Arnot and

Ray Tompkins, the railroad’s primary creditors, had both passed

away and the representatives of their estates moved to liquidate,

and even offered the property for sale. Louis Keller purchased the

majority of the bonds and shares that the Arnot and Tompkins estates

held in the RV in 1921. Keller continued to fund the railroad’s

operation year to year with his own personal finances.

“Meanwhile the

automobile had made its entrance upon the American scene. Improved

roads had begun to erode railroad passenger service, until in 1919;

all daily passenger service was terminated. Occasionally, the Rahway

Valley ran a mixed train, the passenger coach coupled to the end of

the freight to Summit, to keep the State Franchise alive" (McCoy

14

). Passenger service, which had a banner year of bringing in

$10,690 for the railroad in 1918, only accrued $4,920 for the RV in

1919. “In the spring of 1919, Keller ditched the three faithful

coaches, for another motor car, passenger days were surely almost

over” (Young). The Rahway Valley Railroad operated mixed trains, as

well as its one railbus, possibly until as late as 1925. There were

also the labor trains that travelled over the Rahway Valley Line to

Maplewood (a.k.a. Newark Heights), “. . . there was little else of note save for

“worker’s trains” on the Heights Branch. They consisted of the

regular freight bedecked with men going to work, in the cab, on the

tops of cars, and on the pilot" (Young).

|

| Louis Keller,

seen in his later years. Shortly before his death,

Keller acquired controlling interest in the RV from the

Elmira interests that held the majority of the

railroad's debt. Baltusrol Golf

Club. | |

Regarding

RV passenger service, a bizarre news article appeared in a 1920

issue of The Evening Telegram. The article told that the RV

had acquired four jitney buses which it would convert for rail use.

“ With the business

daring of a Jim Hill the Rahway Valley Railroad, which operates the

only “true” freight line between the Grand Canyon of Kenilworth and

the willow-kissed waters of the limpid Rahway River, today hurried a

defi at the Public Service Railway Company which bids fair to put

the skids under the traction company’s anti-jitney drive. The valley

road announced that is come by four pneumatic tired jitneys, each

with a thirty-five passenger capacity, and just as soon as the road

can replace the rubber with steel shoes and cut the wheels to the

measure of the rails there will be inaugurated the first and only

jitney railroad this side of the Sierra Madre Mountains, guaranteed

to do twenty miles to the gallon of gas or better. The announcement

of this revolutionary step in Valley railroading comes at the very

time when the Public Service is looking to the Supreme Court of New

Jersey to scrap all the jitney lines of the State on the ground that

they are infringing on the trolley companies’ franchise, that they

have no legal stains and that they are a nuisance generally and

particularly. Of course, the deluxe, steel tired bus the Rahway

Valley Company proposes will be immune, outside the legal pale, for

it will go and come over its own single track, on its own power . .

. at the company’s pleasure. Up to new Kenilworth, where the valley

road has its Hudson terminal, has been linked with civilization by

Elmer Guy, known throughout the Garden State as the man who has

“mothered” Kenilworth and kept the borough from slipping down the

sloping banks of the Rahway River into oblivion. For fifteen years,

without fear of competition, Elmer has piloted, alone and unenvied,

the only bit of rolling stock, outside of the valley road’s

gondolas, Kenilworth has ever known. Elmer is the whole works on the

Aldene-Kenilworth trolley-motorman, conductor, inspector, switchman,

general supervisor, and often times the motive power. To the borough

this guy is a benediction and a prayer. He brings the children to

school, the mothers to shop, and the town to the movies in

Elizabeth. He calls his line the “Kenilworth Accommodation” and he

has stopped at nothing to suit action to the word, from herding

stray cows to minding babes. Of all Kenilworth Elmer alone views

with alarm the Rahway Valley’s plan to Hylanize the jitney for

railroad passenger purposes. He wonders how the road is going to get

along without traffic cops and how the engineers are going to

affiliate with the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen on their

chauffer licenses. Will the company substitute gasoline for water

towers? Will there be jitney diners and Pullmans? How will the Plumb

Plan affect the venture? These and similar queries have been running

through the mind of Elmer Guy. But the Rahway Valley is determined.

In these days of Phoebe Snows and Chicago Limiteds, of Black Diamond

Expresses and Millionaire Flyers, no progressive railroad . . . can

help get the country back on a peace basis with freight service

alone. And so it comes that the company has sunk surplus, undivided

profits and liabilities into four jitney day coaches and challenged

the Jersey traction ring to do it goldarnedest” (“Jitney’

Train is Railroad’s Defi to Anti-Traction Drive”). Whether

anything ever became of this plan, or if it was ever carried out, is

unknown. Perhaps this article was a dig at Elmer Guy and his trolley

between Kenilworth and Aldene, which had hurt the RV’s passenger

revenues.

The

railroad’s Secretary and General Manager, James S.

Caldwell, and the President of the Rahway Valley Company,

Lessee, Charles

J. Wittenberg, both died in 1919. Rather than pay for

the expense of hiring two men to fill these positions, one man was

hired to fill both. Robert H. England was installed

as President (RVC), Secretary, and General Manager. England, the

self-proclaimed “travelling general manager,” had managed such short

lines as the Dansville & Mount Morris in New York, the Tavares

& Gulf in Florida, and the St. Louis, El Reno, & Western in

Oklahoma.

|

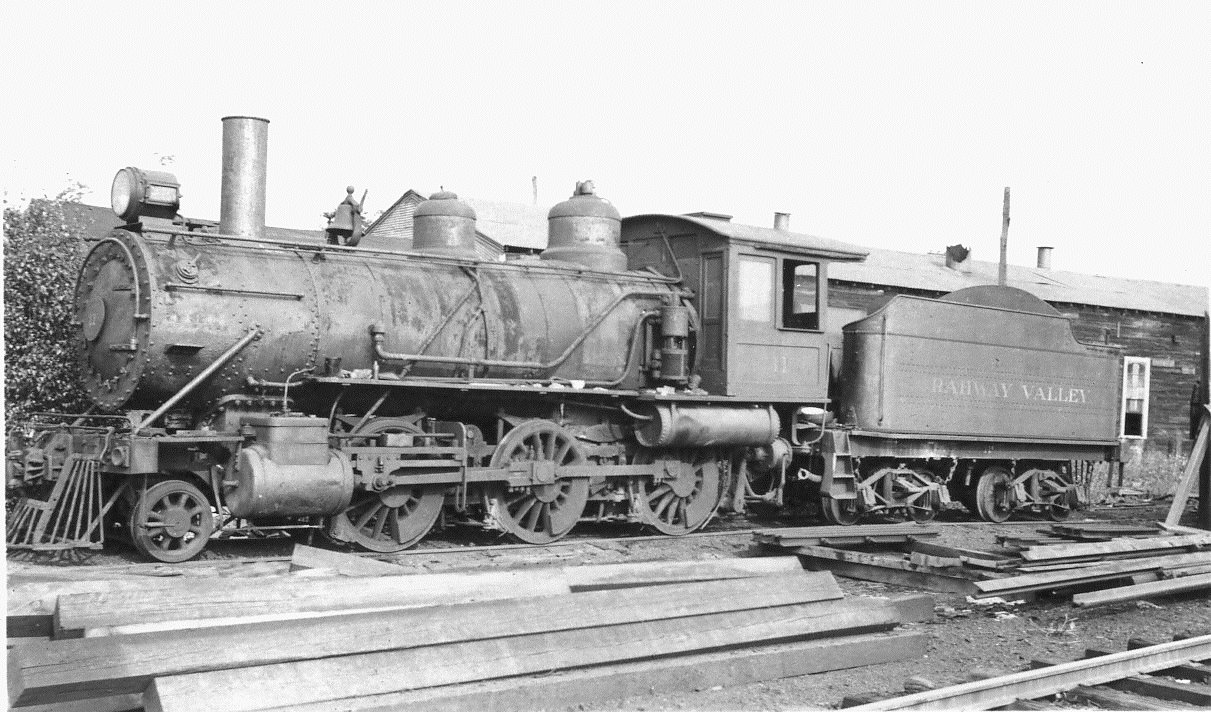

| #11, seen years

later in retirement, was purchased by the RV in

February, 1920. After #8 was rendered out of service in

1923, #11 handled all the RV's trains until the

purchasing of #12 in 1927. #11 was retired in 1933.

| |

As

part of England’s regime of getting the RV “back on track,” a

locomotive was acquired to supplement #8, 9, and 10, all of which had been well

worn by the rush of World War I. The newly acquired locomotive came

from the Grafton & Upton Railroad of Massachusetts, where it was

numbered #5, in February, 1920. Rahway Valley’s #11, a 2-6-0 Mogul, was a 1904

product of the Baldwin Locomotive Works. The two ex-PRR switchers

the RV owned, #9 and #10, were retired in 1920 and 1922,

respectively, and were eventually sold off. #9 and #10 eventually

saw service on the Seaboard

Air Line before being

retired in May, 1930. #8 and #11 remained to handle whatever

business remained along the rails of the Rahway Valley.

In

1919 England had a pamphlet published to entice industrial concerns

to locate their plants along the Rahway Valley Railroad. “The best

industrial sites near New York City are available on the Rahway

Valley Railroad, a belt line connecting and interchanging with all

the trunk lines, accessible to the best labor markets of Newark,

Orange, and Elizabeth, with a population of some 600,000, and also

with motor access on excellent asphalt macadam roads, only 14 miles

to New York City . . . Here the manufacturer may obtain a choice

from some 1,400 acres of land with the necessary railroad sidings .

. . The advantages of a location on such a route is obvious. A

manufacturer on a small road like the Rahway Valley, has the

advantage of the competition of all the trunk lines, so that empty

cars for quick loading and delivery may be obtained from either one

trunk line or the other on short notice, which facilities might not

be forthcoming on a busy line where there would be no competition to

spur the service” (England 808). England also listed the twenty-two

customers of the Rahway Valley at the time, which included coal and

lumber yards, two stone quarries, and two chemical companies, among

others.

|

|

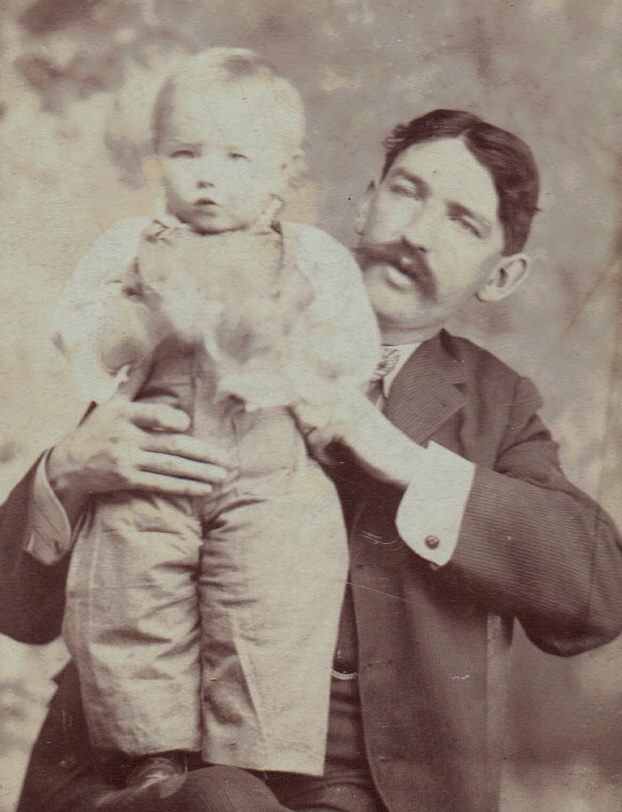

Roger

A. Clark and his young son George, while they still

lived in Rochester, NY. Collection of Carol

Clark

Holden. | |

The

railroad’s inept auditor, Andrew A. Lockwood, was

fired under England’s direction in early 1920. England enticed his

friend, Roger A.

Clark, to fill the position. "There were open fields along the tracks

when . . . Roger A. Clark, came to the Rahway Valley from Oregon in

1920. The thread of circumstance from which the Clarks' story

depends is that . . . [Roger A. Clark], who began railroading as a

traveling auditor on the Buffalo, Rochester, & Pittsburgh, was a

native of Rochester, N.Y. So was Robert H. England. . . Around

1909 England got R.A. Clark to go west as auditor of the Central

Railroad of Oregon . . . Later, R.A. became station agent at Boring,

Ore., for the Portland Railway, Light & Power interurban.

England, who had gone back east to become general manager of the

Rahway Valley, sent for R.A. to help him straighten out the books"

(Young

3).

Feeling his position was

only temporary; Clark came east to New Jersey and initially left his

wife and two children in Oregon pending his return, but the

situation at the Rahway Valley prompted something a bit more long

lasting, ". . . then R.A. decided to move the family to New Jersey

and take a permanent position with the Rahway Valley as auditor.

[His son,] George was hired too, as station agent at Springfield,

NJ. Soon afterward, England left the company, and R.A. was made

president and general manager" (Young

4).

England, not one to sit

still for long, had left the Rahway Valley to pursue other

railroading interests. "When R.A. Clark took over in 1920, with his

son as vice-president, general freight agent, and auditor, the RV

had about 20 customers - a few small manufacturers and a string of

coal and lumber yards. The three largest plants on the line had

closed after World War I. Some 1,400 acres of unoccupied industrial

land along its tracks were going begging. The movie producers who

used the line to make films with such early starts as Guy Coombs and

Anita Stewart had come and gone, and the passenger service, now

operated with railbuses, was on its last legs.” (Young

4).

|

|

George

Clark with his dad Roger, on their way east to New

Jersey in 1920. Collection of Carol Clark

Holden. | |

"When the rest of the nation was

plunged into the depths of a depression, the matter of fact was the

RV actually began to make more money!” (Young).

Roger

Clark rekindled business ties with former customers of the railroad,

and things gradually started to pick up on the line. "Roger Clark, a railroader with much

experience in managing short-line railroads in the Pacific

Northwest. Arriving with his son, George Clark, he found upon taking

over as General Manager, the little pike was sadly neglected and in

default. As realistic men, the Clarks applied their hard-nosed

business experience to rebuilding the road and cultivating the

freight accounts" (McCoy

14). Clark siphoned revenue from anywhere he could

find

it. In addition to freight revenues, additional income came from the

leasing out of the Baltusrol Station (it became a post office

and later an office for Andrew Wilson, a DDT wholesaler) as well

as the Newark Heights Station. “Soliciting new business and reestablishing

old customers aggressively, the new management gradually moved the

balance sheet from red to black" (McCoy

14).

George Clark, Roger’s

son, recalled those early days “Plenty of times I went down to Trenton in those

days and got down on my knees to the tax men . . . We didn't know

from day to day if we were going to make it. We didn't even have the

money to meet our payroll when we started” (Cunningham

38-39

). Roger Clark’s “. . .

regime was marked by

wise and cautious handling of the road’s

business, such as it was, one of which was disposing of the useless

motor car” (Young). All vestiges of RV passenger service were

abolished during the mid-1920s.

Costs were cut wherever

they could be. The railroad used cinders for ballast, discarded railroad

ties as a means to retain fill at several

locations, and the facilities at Kenilworth received maintenance on

an as needed basis. “The repair

shed at Kenilworth, a long wooden structure, was so rickety that one

morning after a high wind the employees came to work to find it

leaning on the engines” (Young

4).

One thing the Clarks

couldn’t ignore, however, was their rag-tag fleet of steam

locomotive power. “The RV owned only one good locomotive” (Young

4) when the Clarks came east to manage the RV in 1920 and that

was #11. “The equipment includes two

engines, No.8, a ten wheel switch, weighing about 140,000 lbs. and

No.11, an eight wheel, light passenger type, weighing about 98,000

lbs. At present No.11 is doing all the work and No.8 is in the shed

at Kenilworth, having broken a set of springs about the first of

April” (Letter to E.E. Loomis from E.H. Boles). With just one

locomotive in service, the RV was in need of some new

equipment.

|

| #12, seen here in

dead storage in Kenilworth, proved too big for use on

the RV. Photo taken by George

Votava. | |

"The Clarks gradually replaced the

worn out locomotives with newer engines” (

McCoy 14

).

Over the span of three years, three locomotives were purchased.

“

Mr. Clark wisely reinvested in some much needed

equipment. In 1929 he scrapped the Engine Number Eight, along with a

pair of little 2-4-0s which had belonged to a hill excavating

company. This firm’s members had left town in a hurry, so he merely

cut up their engines to get the money they owed him” (Young). The

money Clark collected was spent on the purchases of #12, #13, and

#14.

The Rahway Valley’s #12, a 2-8-0 Consolidation

built by ALCo in August, 1902, came from the Bessemer & Lake

Erie Railroad (#96) in September of 1927. The locomotive only

remained in service on the RV for a short while, “No. 12 was the

heaviest engine on the road, too heavy for the 60 [lbs.] rail”

(Taber). Young tells us #12’s fate, “Number Twelve, a “too big”

2-8-0 which had been spreading the rails for two years, was retired,

permanently, when the Eight Spot was scrapped” (Young). The

locomotive remained in the yards at Kenilworth for the better part

of two decades before it was scrapped in 1943.

|

| #14, ex-Lehigh

& New England #20, was purchased by the RV in August

of 1928.

| |

With

#12’s purchase proving to be a fluke, Clark discerningly looked for

a locomotive more befitting the RV’s criteria. He found two. “In

place of them, [#8 and #12], came Numbers Thirteen and Fourteen from

the Lehigh and New England" (Young). The Rahway Valley’s #13 and #14, of the 2-8-0 Consolidation

type, were purchased from Georgia Car & Locomotive in May, 1928

and August, 1928, respectively. These two identical locomotives were

constructed by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1905 for the Lehigh

& New England Railroad as their #19 and #20. They

proved to be well worth the investment and served the RV nobly up

until the arrival of diesel power. #11 remained as standby

power.

Louis Keller, President

(RVRR) and longtime promoter of the Rahway Valley Railroad, had died

in Manhattan, NY on February 16, 1922. “. . . Mr. Keller passed away

leaving his relatives dubiously looking over their heritages, a flat

broke railroad, and a declining social magazine. In accordance with

his wishes, his money and holdings were put into an estate" (Young).

Keller left the majority of his $350,000 estate to his nephews,

Charles Keller Beekman and Louis

Lawrence; and his niece, Catherine Huger.

Beekman was charged with being the executor of his uncle’s estate.

Beekman, an attorney of the firm Beekman &

Bogue (a firm he founded with Morton Bogue), charged his

associate Ralph S. Wolcott with managing the estate. At the time of

his death, Keller held controlling interest in the Rahway Valley

Railroad.

Keller’s heirs,

as well as other RV shareholders, procured lawyers within the

firm of Beekm

an & Bogue to oversee their interests in the railroad.

Lawyers such as Ralph S. Wolcott, Hubert C.

Mandeville, and Louis Weeks, among others, would sit

on the RV’s Board of Directors and fill managerial spots. Of

Keller’s heirs only Louis Lawrence ever sat on the Board of

Directors. The law firm of Beekman & Bogue continued to have

oversight of the Rahway Valley Railroad for the remainder of its

independent common carrier years. Representatives within the firm

would periodically check-in on the day-to-day management at

Kenilworth (the Clarks) and yearly board meetings were held in the

Kenilworth Station. The shareholders of the railroad, and their

representatives within the firm of Beekman & Bogue, maintained a

“hands-off” policy and left the management of the railroad largely

to the Clarks.

.jpg) |

| #13 is seen here

along the rails of the Lackawanna in Summit, just four

short years after the connection was made. 1935.

Photo taken by Homer

Hill. | |

The greatest achievement of Roger

Clark’s term as the line’s chief managerial officer was the

establishment of a connection with the Lackawanna at Summit in 1931.

"At long last, in 1931, the Lackawanna, feeling the effects of the

Great Depression finally agreed to the long delayed connection with

the Rahway Valley. The switch was installed, and at last the

R.V.R.R. became a trunk line" (

McCoy 16

).

Roger Clark, and his son George, had entered into negotiations with

representatives of the Lackawanna just after the onset of the Great

Depression in 1929. The establishment of this connection at Summit

seemed to ensure the coming success of the Rahway Valley Railroad,

“. . . but when R.A. died in 1932 the RV's fortunes were again at

low ebb" (

Young 4

).

Roger A. Clark

died at his home on Morris Ave. in Union on October 3, 1932, he was

62. Clark’s career as a railroader had encompassed positions with

four railroad companies, the Buffalo, Rochester, and Pittsburgh of

New York; the Central Railroad of Oregon and Portland Railway both

of Oregon, and the Rahway Valley Railroad of New Jersey, and

included the saving of the latter. Clark’s later years were marred

by illness resulting from his diabetes. His illness resulted in the

amputation of his legs and his confinement to a wheel chair in his

later years. Despite his ailments, nothing could keep him from his

position as President and General Manager of the Rahway Valley

Railroad.

|