Uploaded May 26,1998

A Man's gotta Do.... Chapter 7

Unlike machinery driven by internal combustion, steam engines possessed idiosyncracies peculiar to themselves, with the result that it often took a skilled and knowledgable hand to get the best, or even the average, out of a particular locomotive. Engines identical in specification would have radically different steaming patterns and control was often more by gifted insight on the part of the engineer than by experience or training.

Such a gifted operator was Woody Woodard.

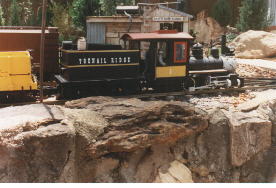

Woody was the engineer of No.9, the 10-wheeler loco that was most commonly assigned to haul the freight cars on the Toenail Ridge Shortline. He could make this cantankerous old engine sing when other drivers had called it every name they could lay their tongues to and walked away from it in disgust and disgruntlement. No.9 had started its life before the turn of the century as a polished and painted high-stepping passenger locomotive in the South-East of the United States. How it came to the Toenail Ridge is a story in itself, but suffice to say that its best days were no longer in front of it and if it had not been for Woody it would have yielded to the scrappers torch years before.

Woodard had learnt his trade in the bilges of steam ships in the Port of Tacoma. He served his time gaining knowledge of the power and intracacies of steam during the hey-day of trans-Pacific shipping between the US and China, when new steamers and the dated sailing clippers exploited the newly opened markets of the Far-East.

He had transferred his knowledge to railroad engines when he followed a lovely young Iowa girl to the valley, where she had gained employment in the office of a thriving lumber-yard. Now he was well established on the Shortline, being regarded as senior engineer. He and his wife Tessie had a little cottage on the outskirts of Selbyville where they raised vegetables and dogs and children.

Steam engines have numerous variables, by altering one setting it is possible to negate the hard-won benefits of another control. When it came to balancing the needs of No.9 against her wants, Woody was a prodigy. He could coax the old girl on slippery rail when she wanted to spin, on bitter still days when she wouldn't draw, when she bucked at poor coal or hard water. He could get her over the Ridge with that extra ton when all she wanted to do was bog down and fail.

It wasn't unusual for an engineer to treat his particular machine like a member of the family, coddling it, chastising it, calling it by pet names or imprecations, depending on its behaviour.

However, regardless of how good and gifted a driver, there are those rare times when all of the Fates conspire to have everything crop up at the same time, and nothing will encourage the recalcitrant locomotive to participate.

Such an occasion just had to occur when No.9 was hauling loaded

reefers to the cheese factory at Selbyville. The temperature had

reached a near record low for the valley, hovering just above

freezing point, a viscious wind was gusting out of the north,

misting sleet was making visibility close to non-existent and the

last load of coal brought in was more dirt than anthracite, so that

the old girl was making hard work of just maintaining a draw through

the stack. Twenty minutes out of Toenail Ridge the line takes a long

curve to the right and then immediately it runs onto the Whibley

truss bridge that spans part of Lake Wallace. Unbeknownst to Woody

or his fireman, that very day Tony Cotton had trundled the Porter

0-4-0 switch-engine to Selbyville with a hot box on the tender.

Unbeknownst to Woody

or his fireman, that very day Tony Cotton had trundled the Porter

0-4-0 switch-engine to Selbyville with a hot box on the tender.

A hot-box is a wheel bearing that is running hot and dry due to lack

of lubrication, or just wear. The tender on the Porter had been

added long after the engine itself had been built. The loco was

originally a side-tank oil-burner but had been drastically modified

to a coal-burning tender loco in the Toenail Ridge workshops.

Anyway, the Porter tender had one axle bearing that was in its last

stages of use, and was vocally protesting its imminent departure

from useful life. So vocally that its noise masked the sinister

sound of the broken drawbar of the oil-tanker parting, leaving

hundreds of gallons of kerosene sitting dead on the track in the

middle of the Whibley bridge and un-missed by the Porter crew as

they struggled to get their crippled little loco the extra few miles

to Selbyville.

The rules governing movements on the Shortline made it very clear to

all crews that no transport or movement of freight cars would occur

unless the consist was completed by a caboose inhabited by a

brakeman.

Except.

A crew may move a single car, at the discretion of the yard-master

in conjunction with the engineer, from one station to the next on

the line, for maintenance-of-way purposes or for humanitarian

reasons, provided that all agree that the move is safe and the line

is clear. And Joe Dempsey, the surly and rum-sodden station-master

at Selbyville had insisted that he had to have kerosene to maintain

the temperature in his station or his old, frail mother was in

danger of shuffling off her mortal coil because of the bitter cold.

Woody Woodard had finally managed to get No.9 to take a decent draw

and was getting some headway on his train as the locomotive exited

the last curve and stepped onto the bridge. The bridge ran straight

and true for over 500 feet, supported at each end by butresses and

in the middle by a brick pillar. He opened the throttle and gave the

engine her head in an effort to pick up time. Finally the old girl

behaved herself and began to surge ahead as the fire drew properly

and increased the heat to the steam-tubes. And then an interesting

but well- documented phenomenon occurred.

Anyone who has lived in a really cold climate will have noticed that

cold affects different surfaces in different ways. Most noticeable,

perhaps, is the way that soil retains heat when artificial surfaces

are deeply chilled. The rails up to the bridge had been absorbing

residual heat from the ballast, thus keeping their temperature

slightly above that of the air. The steel ribbons on the bridge,

however, were exposed on all surfaces, their bases sitting on wood

which was sitting on frigid air. So the bridge rails were coated

with a fine and glittery and above all, slippery coating of ice. And

locomotives hate ice. They express this extreme distaste by refusing

having anything to do with the underlying steel.

The only option an engineer has with a slipping locomotive is to

decrease power to the wheels, in a effort to regain traction. A

speeding slipping engine will continue speeding as the same lack of

forward momentum that causes the slip is the also the lack of

friction to slow the consist down.

"Where in God's name did that come from?" said, Ken, the fireman.

The hot-box on the tender of the Porter finally siezed completely as

Tony brought the engine to a standstill outside the Selbyville

station. As he swung down from the cab he was staggered to see the

lack of tanker where his charge should be. By now the misty rain was

beginning to freeze, falling as horizontal sleet. Visibility faded

to invisibility within twenty feet. Tony groped his way down the

side of the tender past the steaming axle-box on the wheel-truck and

stood scratching his head at the empty track right behind him. With

the realization that it was probably going to cost him his job, he

turned toward the depot to report the missing car to Dempsey, knowing

that the station-master would use his usual sarcasm to demean the

driver.

Five miles out of town, on the bridge, Woody and his fireman Ken had

squeezed past the oil-tanker and discovered the broken draw-bar, so

its presence was explained, if not excused, although as an

experienced engineer Woody could understand the circumstances

combined with the weather that would allow a driver to lose his

train. It couldn't happen with the two big locomotives of the

Toenail Ridge Shortline, as they were both fitted with Westinghouse

safety brakes. By the time

Ken had filled the water tank, the yard man at the cheese factory

had thrown the switch to the spur. Woody had uncoupled the

oil-tanker from the cow-catcher of his locomotive and then hearing

the whistle of his switchman, pulled the loco's reversing lever and

slowly backed the consist into the spur.

Inside the station, Tony had been called every kind of fool and

idiot by Dempsey. The station-master then brusquely shoved past the

Porter's driver and stormed outside to view the damage to the little

engine. And saw the oil-tanker nestled comfortably in its correct

position right behind the tender. Following behind him, Tony's mouth

fell open, his eyes gaped and he uttered expressions that he hadn't

learnt in church. Dempsey went through every level of fury from mild

irritation at being hauled out of his warm building to sheer

thundering fury that Tony would dare to play such a practical joke

on him. So angry was he that he became apoplectic, gasping for

breath and turning a brighter shade of maroon. Clasping his head he

crumbled to the ground, losing consciousness as his blood-pressure

rocketed. Now it's well know that a person who has a fit for whatever

reason, can suffer a bit of memory loss, so when Joe Dempsey found

himself sitting on his station entry in sleet and in reeking wet

clothes, he had no idea how he gotten there. All he realised was

that Tony was being solicitous and caring and making vague noises

about maybe just a drop too much of the liquid refreshment, Mr.

Dempsey, sir.

The three men got the station-master inside to the warmth of his

station, and sat him down alongside of his kerosene stove to recover

and dry. Alexander had long dis-approved of the drinking habits of

the officious agent and made noises about reporting the incident to

the head-office in Rowell. Tony, with the diplomacy of a

vote-seeking politician, began whispering in his ear, giving him the

jist of an idea that a Dempsey controlled was possibly better than a

Dempsey dismissed and perhaps the situation could lead to a better

life all around, both for the crews and the yard workers. Surely

three witnesses to behaviour of which the surposed perpetrator had

no memory at all was a strong inducement to seeing things the other

fellow's way.

And that's how the day ended. Dempsey never remembered what had

happened, but he did know that he had permanently lost control over

many of the men working on the Shortline. Chapter 8 continues the Saga of the Toenail Ridge

Unfortunately the trucks used under the tender were probably old

enough to vote when the tender designer was born. This tends to

happen a lot in back-woods lines, if it's lying around and fits, use

it. If it doesn't fit, leave it lying around some more until

something it fits comes along.

Unfortunately the trucks used under the tender were probably old

enough to vote when the tender designer was born. This tends to

happen a lot in back-woods lines, if it's lying around and fits, use

it. If it doesn't fit, leave it lying around some more until

something it fits comes along.

Some of us may have sheds full of

things like that. This is know by psychologists as "Come-in-handy-

one-day" pre-emptive purchasing, and the waiting handy items have

the official name or "Never-know when-you'll-need-its." These are

often stored with, or in fact can form an undifferentiated

conglomeration with "get-around-to-its."

They begin to slip,

spinning their wheels as their tyres lose traction.

And spinning

causes heat by friction, which melts the ice in the immediate

vicinity, which means that the wheels are now spinning in a little

film of water, so they spin even harder.

But an engine that is not

strongly underway is rapidly impeded by the weight of its train

behind it. So Woody, with much bad language and with extreme

frustration, worked like a slave to restore forward momentum to his

train. And found, regardless of his efforts, that his charge was

quickly losing way. And looked ahead, and saw the oil-tanker slowly

approaching until finally its rear coupler kissed the cow-catcher of

No.9 as the loco was draw to a standstill by its train.

"I have no idea." said Woody, shaking his head and wishing that he

hadn't given up tobacco.

But it had to be done so he faced into the driving freezing

wind and strode across the boardwalk outside the ticket-office and

shouldered the door open.

These brakes worked on a vacuum principle, and if a

car parted from its train, its brake hose separated and caused the

brakes in the whole train to be applied. But Woody knew that the

little Porter had mechanical brakes only, and it didn't take too

much thought to realise the whole situation. He and Ken coupled the

oil-tanker to the front of No.9, pumped up the brake system and

tried to get under way.  The brake-man, Tiny, down in the caboose hadn't

made an appearance during all this time but that wasn't too unusual.

He was probably sound asleep, this being the usual way he passed the

trip. Woody gave three blasts on his whistle and gingerly reversed

the train off the Whibley truss bridge.

The brake-man, Tiny, down in the caboose hadn't

made an appearance during all this time but that wasn't too unusual.

He was probably sound asleep, this being the usual way he passed the

trip. Woody gave three blasts on his whistle and gingerly reversed

the train off the Whibley truss bridge.

They backed up for

half-a-mile and then he slowly began to pull forward, increasing

speed as the locomotive gained traction and momentum. This time when

the engine rounded the curve and began to cross the bridge sheer

speed carried the whole consist along and across the span. In a

matter of minutes they gained the outer marker for Selbyville and

Woody began to apply the brakes in preparation for the arrival at

the station. He glided the locomotive to a halt with its tender

water-hatch perfectly aligned with the spout of the water tank next

to the track.

What he didn't know, due to the shocking visibility,

was that the front end of the oil-tanker had gently nudged itself

against the rear buffer beam of the stationary Porter.

Tony quickly knelt over him, firstly to make sure he was

alive, and then to make sure he was unconscious. He ran into the

station, grabbed the rum bottle from its drawer in Dempsey's

roll-top desk, and darted back to the recumbant station-master, who

was starting to show signs of reviving. Tony quickly emptied the

bottle over Dempsey's head and clothing, threw the empty container

far over the roof of his engine and then bent to revive the fallen

man.  The fireman on the Porter, young Karl from Utah, had been sent by

Tony to fetch Grant Alexander from the Selbyville yard workshops to

repair the siezed bearing. About now he returned with the

yard-master in tow, both of them head down in the face of the biting

wind and sleet.

The fireman on the Porter, young Karl from Utah, had been sent by

Tony to fetch Grant Alexander from the Selbyville yard workshops to

repair the siezed bearing. About now he returned with the

yard-master in tow, both of them head down in the face of the biting

wind and sleet.

The two of them rounded the corner of the station to

see Dempsey being assisted to his feet by Tony, and since they were

down wind of the pair, the rum made its olfactory presence

particularly noticeable. Grasping his opportunity on seeing the two,

Tony said in a carrying voice " Mr. Dempsey, what ever where you

doing outside here, man? I was just on my way in to tell you we'd

arrived!"

Alexander shook his head

at the incredible odds that a draw-bar would break just as an engine

squealed to a halt at its destination with a frozen bearing.

Tony

kept his mouth very, very shut, except for when he ordered a case of

fine sipping Canadian whiskey from Chuck Parker at the saloon and

hand-delivered it to Woody Woodard after hearing about the rescue of

the oil-tanker from Ken, the fireman. Ken found that the major

dollars that he owed Tony from poker were suddenly won back the

next time they played, and for the rest of his life would boast of

how he had once won five straight hands with a pair of twos.

Shortline!