|

Malheur Railroad Fred Herrick Lumber Company |

|

|

|

|

A Malheur Railroad construction train building the railroad between Crane and Burns. Scan from the October 1924 edition of The Timberman. |

|

|

History In 1919 a man named Edward W. Barnes arrived in Harney County to size up the timber availability in the mountains to the north of town. Barnes liked what he saw, and he spent the next several years securing all the private timber he could find and lobbying the U.S. Forest Service to open up the vast Government timberlands in the area to harvesting. Harney County is predominately sagebrush country, and the livestock industry was the primary use of the land. However, fine pine forests were found in elevations above 4,000 feet. President Theodore Roosevelt set aside most of the timber in the Blue and Ochoco Mountains in 1907 through the creation of the forest reserves. The southern reaches of these forests eventually became part of the Malheur National Forest. Through 1920 and 1921 Mr. Barnes returned to Harney County to collect more data and support for his efforts to open the lands to harvesting. Timber cruises estimated that 6,725,000,000 feet of timber lay tributary to Burns, which could provide 68,000,000 board feet of lumber on a sustained yield basis. The Forest Service decided to go ahead with plans to start harvesting the timber, and in 1922 the Bear Valley Timber Sale was advertised to the public. |

|

|

|

|

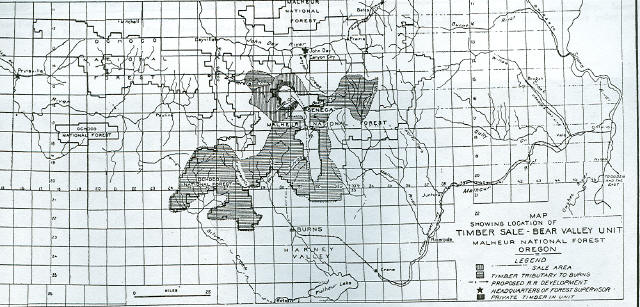

A map of the Bear Valley timber sale from the October 1924 issue of The Timberman. Vertical lines on the map represent the area covered by the sale; Horizontal lines indicates timberlands that were considered to be tributary to Burns. |

|

|

|

The Bear Valley sale stood out as the largest single timber sale ever offered in the northwest. The sale

covered 67,400 acres of timberlands clustered around the headwaters of the Silvies River containing an

estimated 890,000,000 board feet of standing timber. Five species of trees comprised most of the standing

timber: Ponderosa pine (called Western yellow pine at the time) accounted for 770,000,000 feet; Douglas fir

, 78,000,000 feet; Western larch, 30,000,000 feet; White fir, 10,000,000 feet; and Lodgepole pine, 2,000,000 feet.

The sale did come with a couple important stipulations, one requiring that all timber harvested be milled in

Harney county and another requiring construction of a standard gauge common carrier railroad from Crane through Burns

to some point in the Bear Valley. The Forest Service set a minimum bid amount of $2.75 per thousand

board feet for the sale. Mr. Barnes considered this to be too high a price for the sale, especially

considering the stipulations of the sale, and he put the word out far and wide that to place such a bid

would be financially ruinous for any timber operator. Bidding for the sale opened on 22 August 1922, and

no bids were received. The Forest Service re-offered the sale on 4 April 1923, with a minimum bid of $2.00 per thousand board feet. Mr. Barnes apparently talked the Brooks-Scanlon Lumber Company, which had a large sawmill in Bend, into placing a bid at the minimum amount. However, the Fred Herrick Lumber Company placed a bid of $2.80 per thousand, and the contract was awarded to them. Fred Herrick grew up in Michigan. He got involved in the lumber industry in that state when he was 21, and within a few years he owned his own sawmill. Herrick used proceeds from his operations to start other lumber companies in new locations, and before long he had holdings in Michigan, Wisconsin, Alabama and Florida. In 1910 Herrick headed west to Idaho, where he built or bought a number of mills along the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific in the Coeur d'Alene/St. Maries area. Fred Herrick learned about the Bear Valley sale through James V. Girard, who was referred to as "the dean of all the logging engineers in the Forest Service". The two men had worked closely together on many of the timber sales won by Mr. Herrick in Idaho. The Forest Service sent Girard to central Oregon to help the local staff in appraising the timber in the Bear Valley sale, and Girard wasted little time in advising Herrick of the sale and encouraging him to bid. Mr. Barnes had previously purchased a large tract of land just south of Burns that he touted as an ideal mill site, and shortly after Herrick won the sale Barnes offered him the mill site. Herrick accepted the offer, and plans were soon laid out for construction of a grand sawmill on the site. The Forest Service estimated that a total of three separate pieces of railroad would be needed to meet the requirements of the sale. The three were: 1. 30 miles of standard gauge, common carrier railroad running from a connection with the Oregon Short Line at Crane to Burns; 2. 50 miles of standard gauge, common carrier railroad from Burns north to Seneca. This piece of railroad would contain approximately 6 miles of 1.5% grade against loaded cars and 3 miles of 2% grade against empty cars; 3. Short branch lines, ranging from five to ten miles in length, from Seneca into the timber. Herrick formed the Malheur Railroad Company to fulfill the common carrier requirements of the contract. Mr. Frank J. Klobucher was hired to supervise the survey and construction of the railroad. The Malheur Railroad acquired a 100-foot wide right-of-way from Crane through Lawen to Burns. Grading began in September 1923, and the railroad was completed on 24 September 1924. The railroad was fairly easy to build. A total of 30 miles of mainline and 6 miles of yard track and sidings were laid as part of the project. Five bridges were built. The deepest cut on the new line was four feet, and the highest fill stood at eleven feet. Six sidings were established between Crane and Burns to facilitate the shipping and receiving of livestock. Fred Herrick Lumber Company built this railroad with the understanding that the Union Pacific would take it over after the line was completed, and by the close of 1924 the transfer was completed. The line then became the end of the UP's Burns branch (see the Union Pacific page of this website). |

|

|

|

|

Mr. Girard is seen here standing in the deepest cut on the Crane-Burns line. Photo from the October 1924 issue of The Timberman. |

|

|

|

|

One of the bridges completed on the Crane-Burns railroad. Photo from the October 1924 issue of The Timberman. |

|

|

|

Once this first section of track was completed, Herrick turned his attention to complying with the

rest of the terms of the contract. The two biggest priorities were construction of the sawmill and

the extension of the Malheur Railroad north of Burns. However, by this point Mr. Herrick was

encountering problems that would quickly lead to his un-doing. The contract Herrick held called for him to commence cutting on either Forest Service of private lands by 1 April 1925, with cutting on Forest Service lands to start no later than 1 October 1925. However, as noted above, Herrick financed each new venture with proceeds from his established operations, and by the mid-1920's many of his operations were failing. Herrick did what he could with the resources that he had left, but it was not enough to make substantial progress on the line. The Malheur Railroad was encountering significant expensive rock and trestle work in the Poison Creek and Silvies River canyons north of Burns, and with a lack of available money progress slowed to a crawl. A 300-foot long tunnel at the headwaters of Poison Creek was the most serious obstacle faced. April 1924 found Herrick with only 15 miles of completed grade beyond Burns. The Forest Service granted him an extension of time, with a new deadline of 1 October 1926 to commence cutting timber of Forest Service lands. This extension of time came with several stipulations regarding the excavation of the mill pond and laying the foundation for the sawmill. Another stipulation required Herrick to spend at least $100,000 on railroad construction between 1 April and 1 July 1924. In September 1924 the Forest Service modified the contract again, this time making $50,000 in bond forfeitable as liquidated damages if the terms of the revised contract were not met. Herrick still did not have the money available to make the needed progress, and on 1 April 1926 he paid the $50,000 forfeiture. Once again the Forest Service extended the contract, with the railroad to be completed by 15 December 1926 and the sawmill to be completed by 1 March 1927. |

|

|

|

|

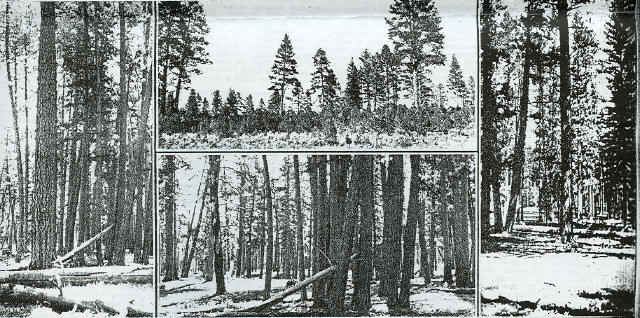

Some examples of the forest types found in the Bear Valley sale. Photo from the October 1924 issue of The Timberman. |

|

|

|

Mr. Barnes watched Herrick closely, looking for an opening to get Herrick removed from the scene. Herrick's

problems gave Barnes that opening, and he swung into action. In September 1925 Barnes initiated legal actions

seeking to get the sawmill site back from Herrick. In November 1925 Barnes announced that he had sufficient

eastern capital to build both a large sawmill in the Bear Valley and 12 miles of railroad to connect the

sawmill to the Malheur Railroad at Seneca. Others in the area grew unhappy with Herrick's progress, and

through late 1926 and into early 1927 the various factions lined up against Herrick and/or the Forest Service

banded together. Their efforts were rewarded in 1927 with a unanimous vote by the Oregon state legislature

requesting a Congressional investigation into the Bear Valley timber sale. Senator Robert Stanfield from

eastern Oregon was more than happy to oblige, and an investigation was launched. Congress held eleven days

of hearings on the case. The investigation found no evidence of collusion or wrongdoing by anybody

involved. Herrick continued to struggle along, doing what he could with what he had, but in the end it

was not enough. In December 1927 the Forest Service gave Herrick two weeks to produce $1.5 million dollars

in additional financing for the Bear Valley project. Herrick was unable to come up with the additional

financing, and on 17 December 1927 the Forest Service cancelled Herrick's contract. Herrick had nearly completed the railroad from Burns to Seneca. The sawmill was also nearly completed, with the mill building, power house, generator building, and mill pond completed. Herrick's total investment in the project stood at around a million and a half dollars. Herrick appealed the decision cancelling his contract to no avail. Herrick attempted to find someone to sell his interests to, but the only party to show real interest in buying up the project was pushed away by Herrick's lawyer. The Forest Service re-advertised the Bear Valley sale in June 1928. Herrick placed a bid of $3.00 per thousand board feet and sought to use the bond from his original bid, which he had been forced to forfeit due to his failures to meet the terms of his prior contract. The Forest Service immediately disqualified Herrick, stating that he was unable to prove his ability to meet the terms of the contract should it be granted to him again. There was another bidder in this round, Edward Hines Lumber Company, which came in with a bid of $2.86 per thousand feet. With Herrick disqualified, Hines got the contract. Herrick reached the end of the line. He sold the mill site, the partially completed mill, and the railroad to Edward Hines for $400,000, which was only a fraction of his investment in the project. By October 1928 Herrick was closing out the last of his affairs in central Oregon and was preparing to leave the area for good. One of his last acts before leaving was to issue the following statement to the Burns Times-Herald: "We came here with clean hands and are going away with clean hands. Through our efforts Burns has a railroad from the outside and a first class railroad to Seneca; a sawmill that was started with the full expectations of our completing it and operating it. The development was started in good faith, and we built with an idea of permanency...I am very much disappointed that financial conditions were such that I could not comply with our contract...I have had to submit to a great sacrifice in sale of price.". The Fred Herrick Lumber Company entered bankruptcy within a week. The story of the Bear Valley timber sale is continued on the Oregon & Northwestern/Edward Hines Lumber Company page of this website. |

|

|

|

|

One more shot of the line built by the Malheur Railroad. This shot was taken near Crane. Photo from the October 1924 issue of The Timberman. |

|

|

|

Map

Solid line shows trackage completed by the Malheur Railroad; Dashed line shows the trackage started but not finished. |

|

|

All time locomotive roster Underlined numbers indicate a link to a page of pictures of that locomotive. #7564- Baldwin 2-8-0, c/n 18718, built 1901. Ordered by Simpson Logging Company, but delivered instead to Phoenix Logging Company, Potlatch, Washington, where it carried the name Coo-Ley Ku-I-Tan but apparently no number. To Bellingham Bay & British Columbia Railroad #8; to Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific #7564 12/1918; to Fred Herrick Lumber Company #7564 12/22/1926; to Edward Hines Westerm Pine 1928. Scrapped circa 1930. |

|

|

|

References Books "Green Gold: The incomplete, and probably inaccurate, history of the timber industry in parts of Central and Eastern Oregon from 1867 to near the present". Martin Gario Morisette, self published, 2005. "When the Railroad Leaves Town: American Communities in the Age of Rail Line Abandonment, Volume 2". Joseph P. Schwieterman, Truman State University Press, 2004. Periodicals "Frontier Enterprise versus the Modern Age: Fred Herrick and the Closing of the Lumberman's Frontier" by Thomas R. Cox, January 1993 Pacific Northwest Quarterly: Pgs 19-29. "Development of New Oregon Pine Section" by Jno. D. Guthrie, October 1924 The Timberman. |

|

|