INDUSTRIAL & TERMINAL RAILROADS &

RAIL-MARINE OPERATIONS

OF BROOKLYN, QUEENS, STATEN

ISLAND, BRONX &

MANHATTAN:

| What you think you know about the Kaufman Act: Steam Locomotive Legislation, Regulations and Restrictions in and around the City of New York: 1834 - 1930 . everything prior to and up to the Kaufman Act, including its being found unconstitutional in 1926 and its repeal in 1930; . . and the: . . #8835 - the Model X3-1 General Electric / Ingersoll Rand oil-electric slow speed switching locomotive . the first successful diesel-electric locomotive in New York City . .by Philip M. Goldstein |

|

| updated: 04 October 2025 - 20:55 CDT | ||

| update summary | date | location |

| GE / IR demonstrator 8835 catalog added | 10/4/2025 | 1924: The Prototype X3-1: GE / IR #8835 |

| Kaufman Act - major revelation - it was unconstitutional, overturned and repealed | 9/28/2025 | Steam Locomotive Regulations within the City of New York |

"A social bot, also described as a social A.I. or social algorithm, is a software agent that communicates autonomously on social media. The messages (e.g. tweets) it distributes can be simple and operate in groups and various configurations with partial human control (hybrid) via algorithm. Social bots can also use artificial intelligence and machine learning to express messages in more natural human dialogue..

Social bots are used for a large number of purposes on a variety of social media platforms, including Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube. One common use of social bots is to inflate a social media user's apparent popularity, usually by artificially manipulating their engagement metrics with large volumes of fake likes, reposts, or replies. Social bots can similarly be used to artificially inflate a user's follower count with fake followers, creating a false perception of a larger and more influential online following than is the case.

The use of social bots to create the impression of a large social media influence allows individuals, brands, and organizations to attract a higher number of human followers and boost their online presence. Fake engagement can be bought and sold in the black market of social media engagement."

"What is the cost of lies? It's not that we'll mistake them for the truth. The real danger is that if we hear enough lies, then we no longer recognize the truth at all."

Philip M. Goldstein

"The immediate purpose of this bill is to require the New York Central Railroad to remove its tracks from the surface of Eleventh Avenue, in said city, and so to terminate the present use of said avenue by said railroad, which is now operated by steam locomotive power at grade."The major issues with the bill, was despite the fact that the City of New York and the New York Central Railroad reached a tentative agreement, the State of New York legislature could not pass it. Therefore, the City simply did not have the financial capital to make restitution to the railroad for condemned property and make this a reality.

The first passenger railroad to ply a route on Manhattan was the New

York & Harlem Railroad, organized in 1831. Their first section of

the line to open for service was along the Bowery from Prince Street

north to (East) 14th Street. This opening took place on November 26,

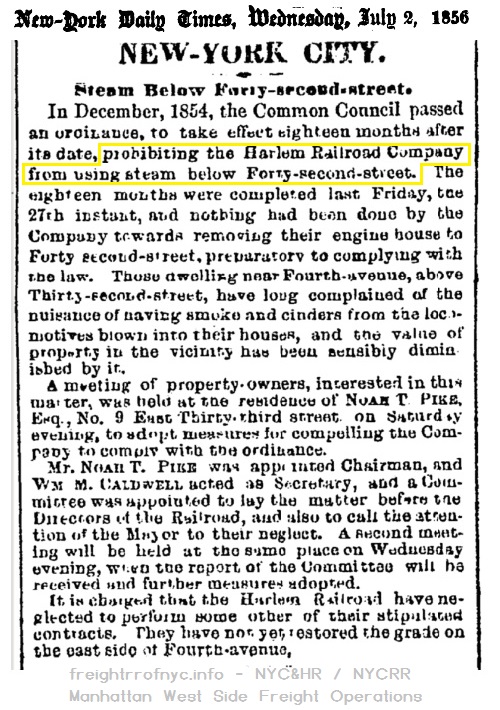

1832. After that, the following sections opened:. Following at least one boiler explosion in 1834, fear from this incident; as well as outcry from residents along the route about the nuisance of smoke cinders, and hissing steam, which was causing a great stir among the livestock on their farms (yes, hard to believe that this area still had farmland at this point!) and in some instances where the trains were hitting cows. So an ordinance was passed in 1834 prohibiting the steam locomotives south of 14th Street. The steam locomotive was uncoupled from the passenger car, a team of horses brought in, hooked up and the passenger car brought south. As I understand it, if a train consisted of more than one passenger car, each passenger car needed its own team of horses, so if the train consisted of three cars, three teams of horses would be bringing three individual passenger cars south. "A new practice arose. At the steam terminal, at Fourth Avenue and Fourteenth street, incoming trains were broken up and one by one the cars were drawn by horses the rest of the day down to Chatham street terminal at Broadway, opposite Saint Paul's. And the horse-drawn cars, northbound, were made up into trains on reaching the steam terminal and thence drawn by locomotives..." ("Grand Central" No Place For A Railroad, by David Marshall, Whittlesley House - McGraw Hill; 1946)A very labor intensive and time consuming practice to say the least. Regardless of that, this ordinance only applied to the New York and Harlem's route along Fourth Avenue, the Bowery, and Centre Street (not that there were any other railroads in Manhattan at this time.) |

|

| So I reiterate: this regulation only applied to the New York & Harlem Railroad operation along Fourth Avenue, south of 42nd Street. |

"The charter of 1846 granted the right, subject to permission from the City of New York, to build a line down the West Side of Manhattan. That permission was given the next year, and the West Side tracks were laid as part of the Hudson River Railroad.

The line handled passenger as well as freight business, inasmuch as the Park Avenue line to what is now Grand Central Station belonged to an entirely different company, the New York & Harlem Railroad Company.

The Hudson River Railroad Company established a passenger station at Chambers Street, but drew its passenger cars by horses between that point and Thirtieth Street.

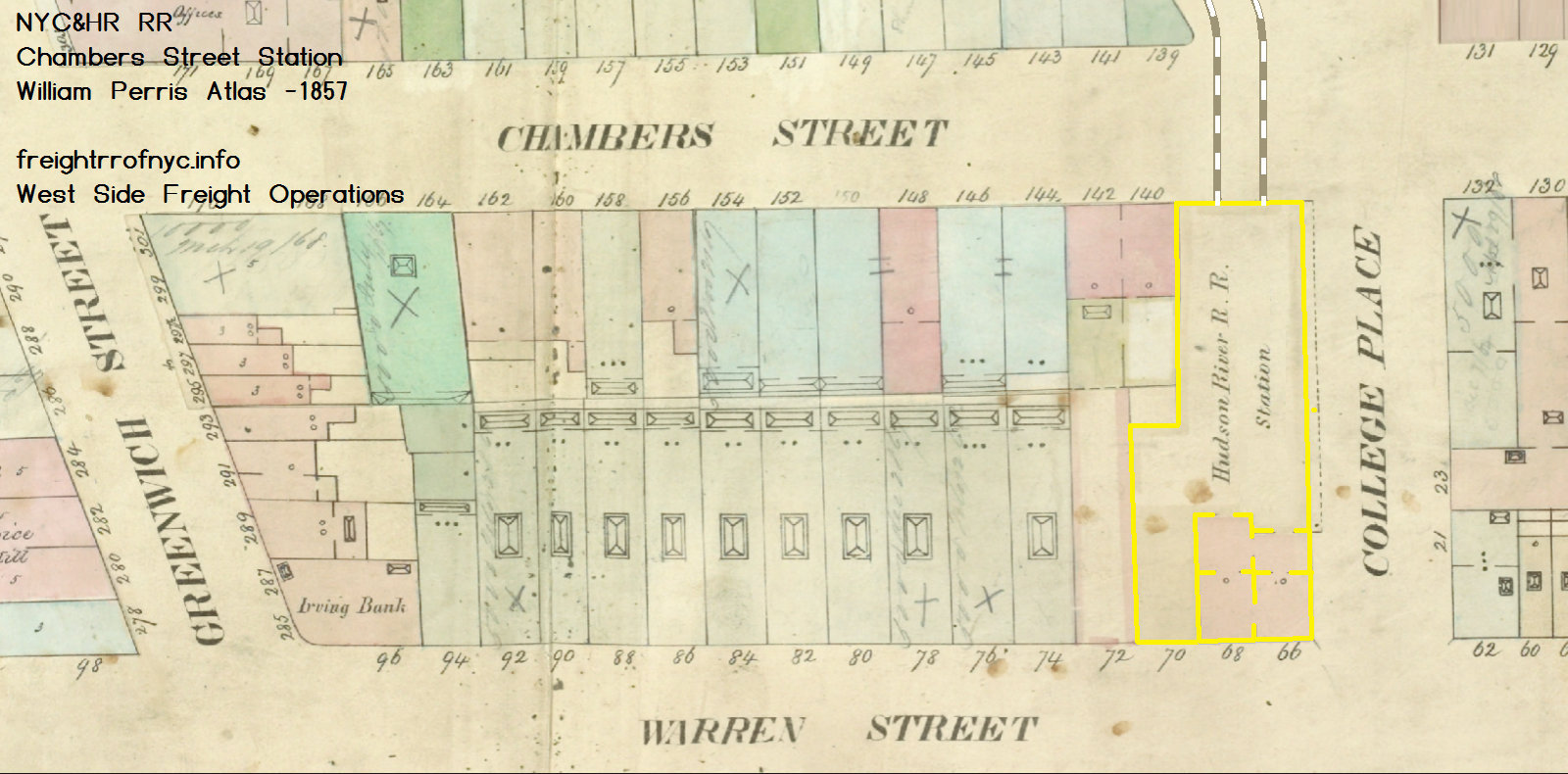

So, not only was the Hudson River RR now permitted to use steam

locomotives, but it was in fact using them in joint freight and

passenger handling to and from the Chambers Street Station until 1868.  Atlases of New York City - Manhattan - 1857 Plate 8 - William Perris Civil Engineer and Surveyor Third Edition Publisher: Perris & Browne Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division New York Public Library Digital Collection annotated version © 2024~ freightrrofnyc.info added 20 May 2024 |

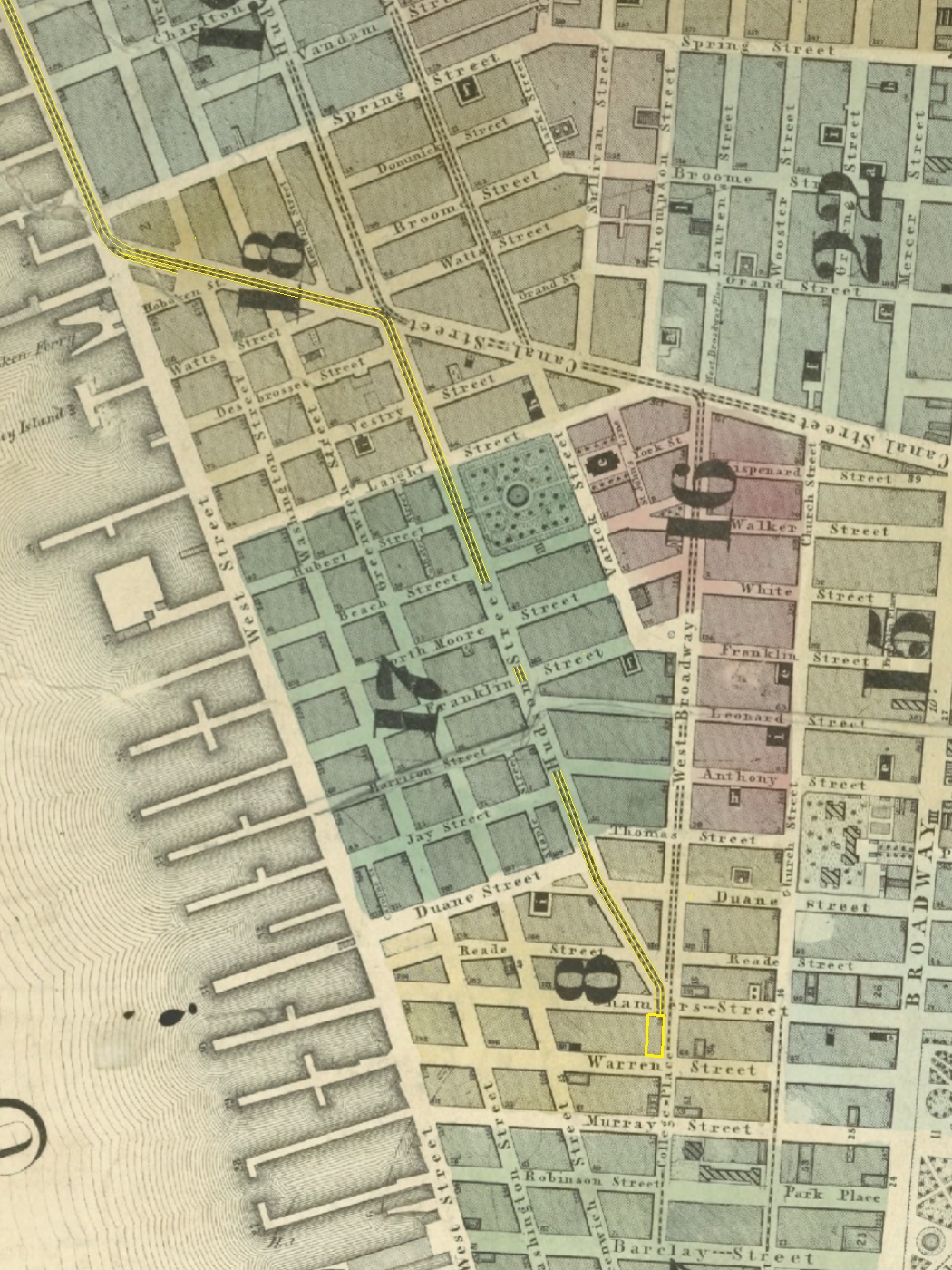

Atlases of New York City - Manhattan - 1857 Index Map William Perris Civil Engineer and Surveyor Third Edition Publisher: Perris & Browne Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division New York Public Library Digital Collection annotated version © 2024~ freightrrofnyc.info added 20 May 2024 |

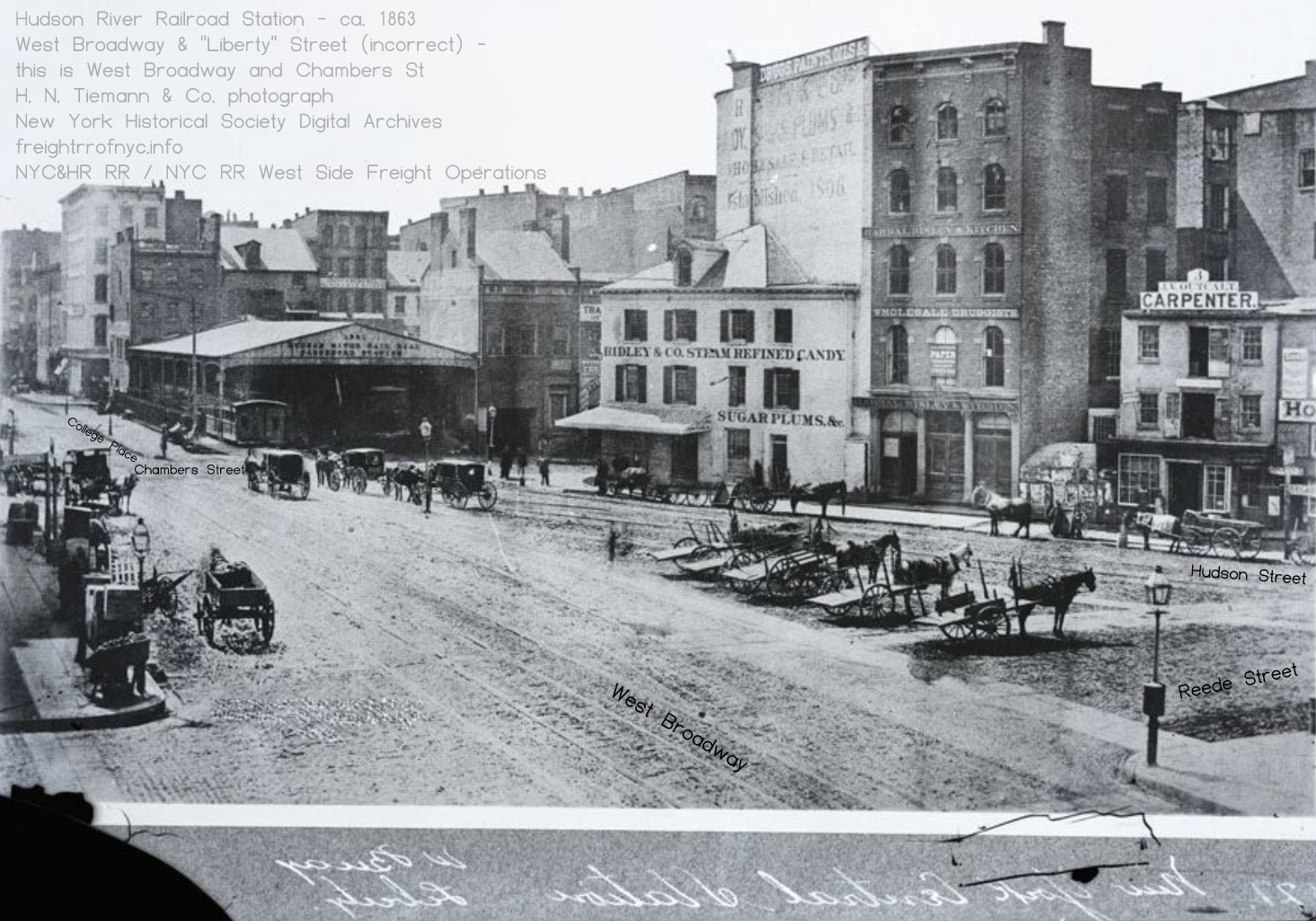

Hudson River Railroad Station Passenger Station - 1863 H. N. Tiemann photo New York Historical Society Digital Archives image id: NYHS PR129 b-07 327-01 annotated version © 2024~ freightrrofnyc.info added 20 May 2024 |

|

The line handled passenger as well as freight business, inasmuch as the Park Avenue line to what is now Grand Central Station belonged to an entirely different company, the New York & Harlem Railroad Company.

The Hudson River Railroad Company established a passenger station at Chambers Street, but drew its passenger cars by horses between that point and Thirtieth Street.

The company's freight traffic grew to such an extent that the company was forced to find a site inland from the waterfront for a downtown terminal. On this site, at Beach and Varick Streets, was built the St. Johns Park Terminal, after which, in 1868 , the tracks south to Chambers Street were removed.

| In

1850 and again in 1863, the Common Counsel of the City of New York

granted permission for the Hudson River Railroad to use "dummy engines" south of West 30th Street to Chambers Street. |

|

|

Chapter 425 - Laws of 1903, Section 4:

Shall not be lawful, except only in case of necessity, arising from the temporary failure of such other motive power as may be lawfully adopted, for any railroad corporation to operate trains by steam locomotives in Park avenue in the city of New York south of the Harlem river. If trains shall be operated by steam locomotives in said Park avenue south of the Harlem river for a period of more than three days, the railroad corporation operating such trains shall pay to the city of New York a penalty of five hundred dollars for every day or part of day during which such trains are so operated, unless the mayor of the city of New York shall certify to the necessity for the use of steam locomotives arising from the temporary failure of other motive power."

"the New York and Harlem Railroad, the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, and any successor companies using the railroad right of way in Park Avenue, "are hereby authorized to run their trains by electricity, or by compressed air, or by any motive power other than steam and which does not involve combustion in the motors themselves, through the tunnel and over the improvements."

New York Central & Hudson River / New York Central RR: Manhattan Freight Operations

Pennsylvania RR: West 37th St Freight Station (PRR)

Erie RR: West 28th St Freight Station

Lehigh Valley RR: West 27th St Freight Yard

Baltimore & Ohio RR: West 26th St Freight Station

|

This 1908 regulation was specific as to the prohibition of steam locomotive operations in

the Park Avenue Tunnel,

and nowhere else in Manhattan or the remainder of the City of New York, including any of other four boroughs (Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx and Staten Island). |

| Mervin Clark Stanley was born May 6, 1857 in New Britain, Hartford County, Connecticut. He was the son of Oliver Cromwell Stanley and Charlotte Stanley, née Hine. He became a lumber, coal and builders' supplies merchant in New Britain. On January 23, 1884, he married Martha Fenn Miles. In 1899, he relocated to New York City, and became a partner in a firm of commission merchants and exporters. Mervin entered politics as a Republican, and became a personal friend of Governor Charles Evans Hughes. Stanley was a member of the New York State Assembly in 1905, 1906 (New York County, 19th District) and 1907 (New York County, 15th District) He died on February 1, 1907, at his home at 329 West 82nd Street in Manhattan, after undergoing two operations for appendicitis; and was interred at the Fairview Cemetery in New Britain, CT |

|

|

Martin Saxe was born August 28, 1874 in New York City. Martin was the son of Fabian Sachs and Theresa Sachs, née Helburn. He graduated from Princeton University in 1893. Saxe was a member of the New York State Senate (R) from 1905 to 1908, sitting in the 128th, 129th (both 17th District), and the 130th and 131st New York State Legislatures (both 18th District.) In April 1915, he was appointed to a three-year term as Chairman of the State Tax Commission. He died on February 5, 1967, at his home at 101 Central Park West in Manhattan. |

|

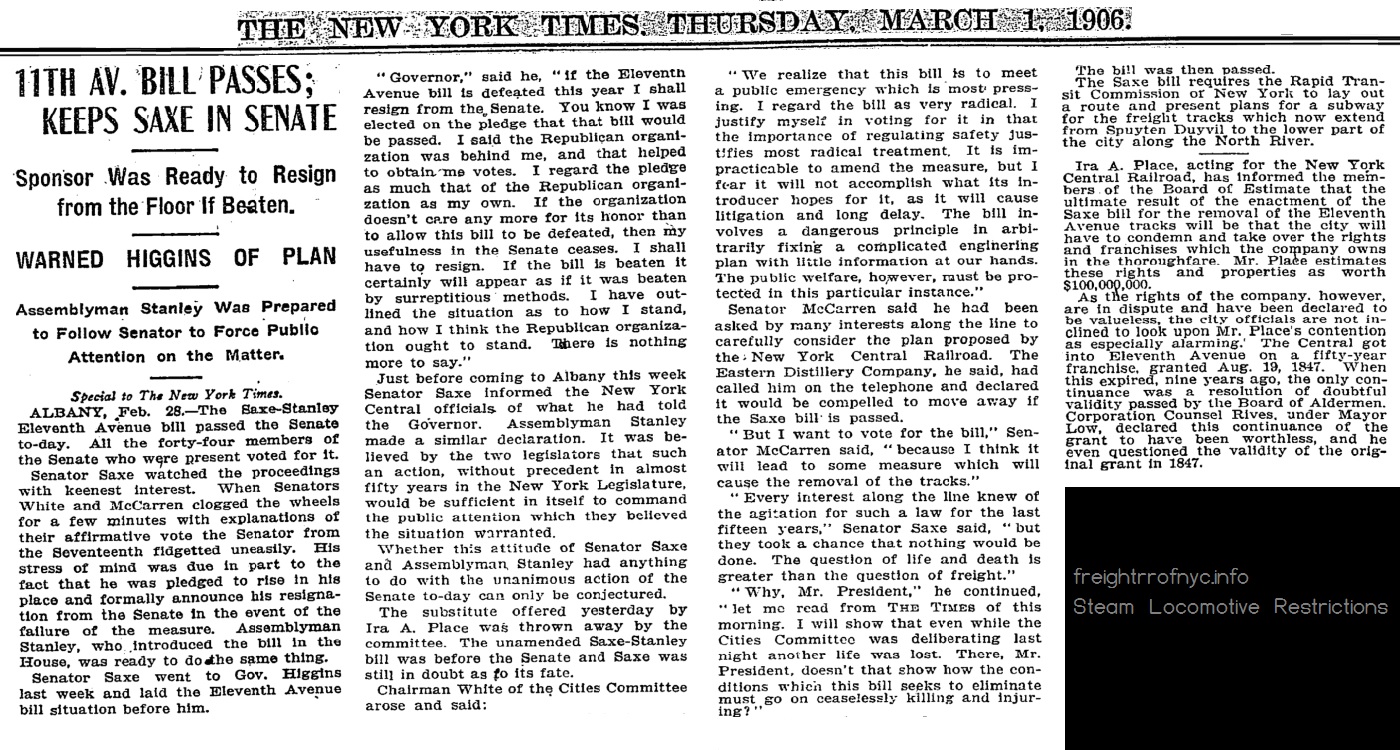

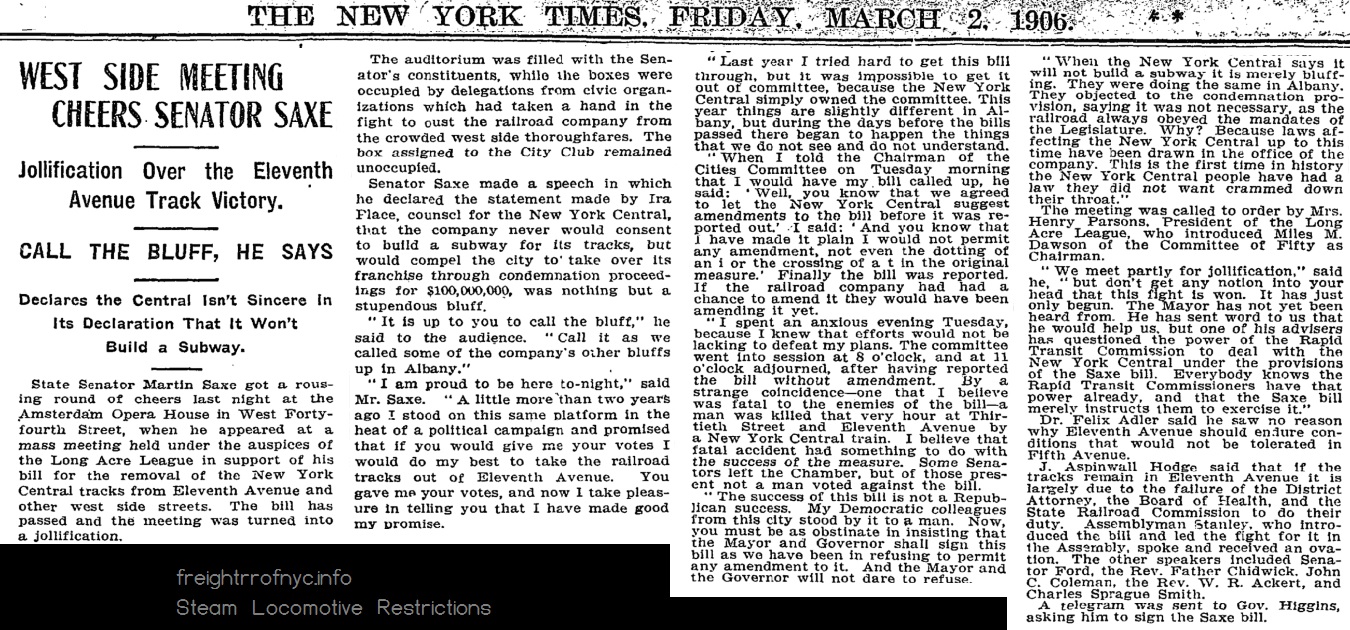

One of the more amusing tidbits from this Saxe Bill, was the fact that

Senator Saxe threatened to "resign" from the Senate if the measure

failed. And you think a politician threatening to quit or "move to Canada" if their bill was voted down (or their political party was voted out) was new? Despite the revelry we will see in the next pair of New York Times articles, the matter-of-fact truth as stated by the Ira A. Place of the New York Central says it clearly:

To what the cost of this victory would be to the City of New York? |

|

|

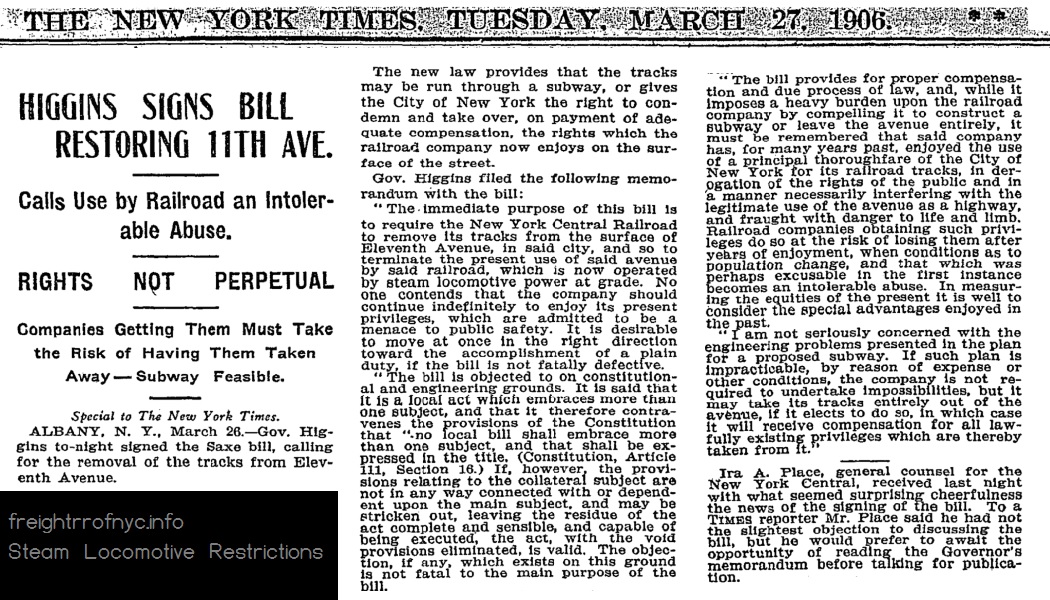

| With this article, Governor Frank W. Higgins (R) signed the Saxe bill into law. His memorandum, quite lengthy, is not as boastful as Saxe's statements were several weeks prior. But again, the City and State prevailed to what degree, with the passage of this act? So what did the Saxe bill really accomplish? Here, hindsight is 20/20. We know from history now, that the New York Central Railroad was not forced from its Eleventh Avenue street running; the City would find out soon enough that the State of New York ratified the bill, but was not interested in financing the reimbursements following condemnation proceedings. The New York Central would continue to operate in the streets of Manhattan for another 35 years. |

|

"These were the only plans prepared by the Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners and they formed the basis of all negotiations between the board and the officials of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad Company. It will be observed that this plan does not comply with the provisions of the act which provides for a plan for a subway to which all tracks now operated at grade should be removed."

A bill designed to authorize the plan was introduced in the legislature but failed to pass, with the result that the procedure prescribed by the Saxe Act was left in force.

The Saxe Act prescribed by Section 4 that in case the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners should be unable within twelve months to come to an agreement, then condemnation proceedings should be instituted.

"In case the board of rapid transit commissioners shall be unable within twelve months after this act takes effect (the act took effect March 26, 1906) to agree as herein provided with said railroad company upon a plan as contained in the preceding section and obtain the approval thereof of the board of estimate and apportionment , the said board of rapid transit commissioners shall thereupon condemn all and any rights,privileges and franchises of any such railroad company or companies to operate by locomotives using steam or other power, cars or trains for carrying freight and passengers at grade on, across, through or along streets , avenues, public parks or places of the City of New York, Borough of Manhattan, and cause the tracks of such railroad or railroads, to be removed therefrom."

PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION - FIRST DISTRICT - REPORT FOR 1907 - pages 53-59, following excerpt from p. 55-56

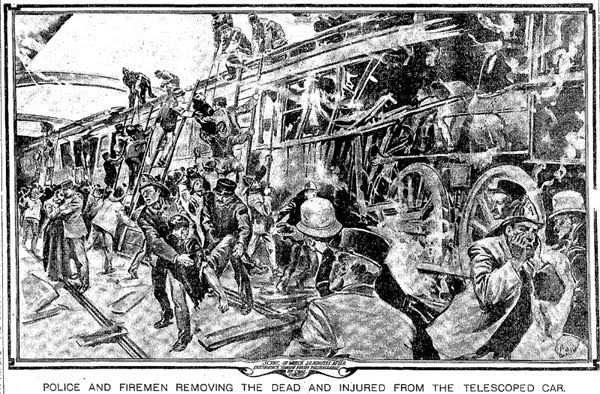

Methods of Relief- Eleventh Avenue.- From the foregoing it will be seen that the mandatory provisions of the law have been complied with. But some method of sinking or elevating these tracks must be found. For many years the situation has been growing worse and worse. Children are killed, needed streets are rendered almost impassable, traffic is constantly impeded by freight trains, and a large portion of an important section of the city finds its progress retarded.

The probable award on condemnation would impose a serious burden of payment upon the city, and moreover some railroad access to the westerly part of the city to bring into market produce, meat, milk and merchandise, is desirable. The solution, therefore, rests rather in the replacement of the tracks than in their entire removal.

- High Cost: The pursuit and attainment of the victory involved significant sacrifices, loss of business, resources, or cost of living.

- Lack of Fulfillment: Despite winning, the victor feels no satisfaction or joy because the victory doesn't deliver what was hoped for or makes their situation worse.

- Damaged Progress: The victory may have even hindered long-term goals or caused irreparable damage, such as destroying businesses or societal stability.

| The Saxe Bill was the first attempt to solve the West Side Problem (street running of freight trains.) Failed. |

.

.

| In 1908, a New York

Times article reported that during the preceding decade nearly two

hundred people had been killed, mostly children; from nearby tenements.

But it was the "gruesome death" of a school boy that supposedly stirred the call to

eliminate the trains from the West Side. On Monday, September 25, 1908; seven year old Seth Low Hascamp and a group of friends were playing "follow my leader"; of which their route included climbing upon and over the cars of a freight train that had stopped in the middle of Eleventh Avenue at the intersection of West 35th Street. While upon the freight cars, the cars began moving and Seth was thrown from the car to beneath the wheels and crushed. Although it has been postulated that it was illegal for trains to stop at the location in order to avoid such accidents, and the people were quick to blame the conductor or the brakemen, who were allegedly "not be in their proper places" when the train suddenly started moving again. Let us analyze this for a moment. "Illegal to stop the train." What if the train had been stopped because of a pedestrian or horse and wagon in their way? Are we to presume the train was to keep going and run over the person or horse instead to abide by the regulation? And would this not bring us right back to where we are: an unnecessary death caused by the freight operations in the street? Whether the train was moving, or standing still; it would have still presented a danger; but an avoidable danger. A preventable danger, by not getting close to it. Lo & behold, that was exactly why the train was stopped it was found that the train had been compelled to stop by a truck which was on the tracks! Stop or don't stop, the railroad is damned if does and damned if it doesn't. It's said the "conductor and brakemen were not in their proper places". |

|

Were the conductor and / or brakeman hoisting a few in a neighborhood bar, while they were supposed to be on duty (and truly would have been not where they belonged)? Or was the conductor at the front of the train asking the truck to move; and the brakeman at the rear of the train, protecting the movement like they should have been; and truly in their rightful places, just not at the "right place and right time" to prevent Seth and his friends from playing on the train?

If the train was truly "five blocks in length" (which equals 1300 feet, measuring the frontage of the city blocks along the route the train would be taking), that would have equated to 32 freight cars of 36 foot length common to that era. In my research, I have yet to see a train of 32 freight cars along Eleventh or Tenth Avenues in any of the imagery preserved from 1908. The trains are usually ten to fifteen cars at most. But let us assume Mr. Schroeder's accounting was not hyperbole or exaggeration. If the brakemen was where he was supposed to be, (at the rear of the train) he probably couldn't see Seth or his friends playing near the middle of the train. Not with horses and vehicles on both sides of the train going to an fro and the avenue, all well as regular pedestrians. Think of it like this: can you spot a friend in a city crowd from several blocks away, keeping in mind you are actually looking for your friend?

Remember, the neither the conductor or the brakeman was employed to be a crossing guard or a policeman. Their job was to move and control the train. Subsequently, the crew of the train involved was exonerated by the jury of the coroner, Dr. George Frederick Shrady, Jr; and blamed the accident on the child’s own negligence.

And in a classic case of 'the truth hurts', the coroner's decision ignited a wave of anger. A

protest march was organized and held on the evening of Saturday, October

24th; where five hundred children parading in silence up Eleventh

Avenue carrying placards demanding that freight trains be removed from

the city streets.

And to add further insult to injury, Mr. Schroeder marchs

these children up the avenue on the very railroad tracks that presented

the danger:

"to the beat of a drum and the light of fireworks (fireworks on a somber protest processional?) the little ones moved up Eleventh Avenue along the tracks of the railroad."

I also take note of the following sentence:

"Once, when a long freight train passed over the tracks, the procession and the congs [sic] gave way to a chorus of jeers and howls directed at the crew of the train."

So; in fact, the trains are visible and audible at this time of evening (the march taking place at 7:00 pm, that the procession could see the train coming, and to get out of the way of it in time. Are you meaning to tell me the train didn't just jump out of a dark alley or side street in a flash and run them over? Furthermore, in the interest of safety, should not the protest be held on the sidewalks in front of the railroad yard, or better yet in front of corporate headquarters of the New York Central Railroad at Grand Central Station? Because marching them up a busy thoroughfare at 7 pm seems like a much better (and more dramatic) choice.

Henry Schroeder, (also referred to as Mr. Schneider in the

newspaper article above) was the secretary of the newly formed “Track

Removal Association,” and he went on record that on dark winter

afternoons an average of three school children were killed every month.

Tragic as this was, and still would be in the present day; children

cross in front of buses; dart out from between parked cars; and take

uneducated risks that they aren't aware of. Younger children, haven't

accrued the necessary experiences of recognizing hazards. Parents and

guardians can

only do so much to teach youngsters the hazard of crossing a street, or

playing where they shouldn't.

If this

was truly the case; why didn't Mr. Schroeder

raise the necessary funds and hire crossing guards during these dark

winter afternoons to protect the children at intersections where the

train ran; like

schools do today adjacent to busy thoroughfares? It is a very simple

premise, and would have eliminated or at least curtailed the

problematic situation; as he declared it to be.

But in retrospect, those crossing guards, had they been hired and in place are at designated intersections. If Seth and his friends were mid-block, between two crossing guards; the guards might have missed them too.

What cannot be alleviated, is the natural inquisitiveness of children that draws them to industrial objects (including myself) when we were younger. What we do know for fact, is children explore abandoned buildings, sit in abandoned cars pretending to drive, climb on standing railroad equipment, place pennies on the rails, light fireworks with short fuses; hitching a free ride on the back of city buses to beat the fare.

The list of potential hazards that could result in injury, or worse; is endless.

Let me relate the following personal experience. When I was 8 years old, and the Blizzard of 1978 hit New York City with 30+ inches of snow; the side streets were impassable in Brooklyn. My friend and I built a tunnel network under the snow in the street. We took snacks into the tunnels and had a blast. Not long after, my father found out and he was livid. After he calmed down, he explained to me what could have happened when the city snow plow would have come down the street? Obviously, we wouldn't have been seen in the snow tunnel and likely would have been crushed to death. It was then, and only then; did that fun evaporate and replaced with images of pain and dismemberment.

Would it have been my fathers fault had I been killed? Would it have been the fault of the driver of the Department of Sanitation plow truck? Was it mine? In my mind; yes, it would have been, because I was responsible (or irresponsible) for my own actions. But remember, I too was the same age as young Seth. I, like him; did not have the experience in life at the age of eight; to recognize a dangerous / fatal situation in a seemingly innocuous one. My friend and I were simply having fun at the time.

I will not get into the debate of, "Where were Seth's parents?", "Why wasn't he in school?" (it was a Monday), or if the parents did or did not attempt to educate him to the rationale of "if your friends jumped off a bridge, are you going to jump too? The natural and innocent inquisitiveness and carelessness of youth is to blame for young Seth's death. My father just happened to be coming out to shovel our sidewalk. What if he wasn't? Would I be here today writing this?

Seth could just have easily fallen out of a window or off the tenement roof playing the game. Would there have been as much outrage then? Would some person use Seth's death to champion a "cause" against a landlord as much as they did against the freight train operations on the West Side?

In short, we see that todays modern reaction is to blame someone else for these failings, existed back then as well.

We as a society, attempt to educate youth to the dangers of illegal drugs; driving while distracted; caving to peer pressure; etcetera and so forth. But, quite honestly, we fail.

Why? Because society has not learned from its mistakes. And it

will not. Currently, there is a resurgence of these risky acts of

derring-do;

adolescents and teenagers in New York City and all over the globe are "subway surfing";

that is climbing on top of moving subway cars and trains and riding

on the roof while the train in moving. More than several have been injured or killed when they struck

the tunnel roof, overpasses or fell off the moving train.

But does present day society demand the abolition of New

York City

subway service as a result? No. A few attempt to lay blame with the

New York City Transit System, and demand the transit system be

proactive with installation of (even

more) gates; fences; locking the doors of the subway cars so the

perpetrators can't egress to the roof between cars. (But then these

same people complain when the

doors are locked preventing them from leaving a crowded car or in case

of an emergency.) People demand the installation of video surveillance

cameras; hiring more police; along with other knee jerk but equally

useless

reactions. You can hire 100,000 more police, but will they be in the

right place at the right time? Most often not. These juveniles are

known to go to extreme lengths to perform the subway surfing. They

climb on the roofs of elevated

stations to reach the subway cars roofs. Any obstacle placed in their

way, they will find a way to circumvent.

In today's era; we see some of the viral postings online involve hitching a ride long distance on freight trains, trying to emulate the romance of the rail during hobo days. Back then, most hobos rode the rails seeking employment during the Great Depression, not for fun. They knew they could lose their lives from slip or fall, or at the hands of a particularly brutal conductor. Today's "hobos" ride "to do it", and to podcast their adventures.

But we also bear witness to other foolhardy "dares" where juveniles (and some young adults) give into "challenges" posted on viral media, et al: biting into laundry detergent pods "the Tide Pod Challenge"; "sunburn art"; "Nyquil chicken"; walking in the street blindfolded a/k/a "bird box challenge."

It is not the fault of the laundry detergent or cough medicine manufacturers. Medical professionals have been warning people for decades about the dangers of smoking. Yet, despite those warnings some elect to do it anyway. Some do it to look cool. Some do it to fit in. They weren't forced to do it; they did so voluntarily. In the case of cigarettes or or drugs or alcohol; those substances have the added danger of addiction.

Simple fact of the

matter is, these deaths occur from nothing more that the very human

trait of free will (and foolishness). The rush of adrenaline from these

feats of daring

do, showing off to friends and strangers; are to blame for the subway

surfing incidents. In short, we see and like to think that todays

modern reaction to

blame someone else for these failings; existing back then, as well.

And yet the news is still full of tales of lives taken too early, children and adults alike. Adult vehicle

drivers too impatient to wait at a grade crossing, go around the gates and get hit by the

train. Under-trained commercial tractor-trailer drivers bottoming out

on railroad crossings, getting stuck and then getting struck. People

taking a short cut and walking on railroad tracks; and some of them

wearing earbuds listening to music and don't hear the train blowing its horn.

Nor were / are these deaths the fault of the New York Central Railroad freight operations back in 1908, nor is it the fault of the New York City Transit System or the freight railroads of today.

But obviously back then, like now, it is easy to blame the railroads and accuse them of fault or negligence. "I didn't hear the locomotive blow its horn." "The conductor and brakemen were in the wrong place." "Why does the railroad go through the center of town, where it's busiest?"

Blame the railroad, because it is easier than taking responsibility for one's own actions.

| As discussed in many pages of the website; the steam dummy or dummy engine was a steam powered locomotive with a wood carbody enclosing and covering the locomotive: This was supposedly done to prevent the frightening of horses, which would cause the horse to rear, buck or run amok. Supposedly, horses had became conditioned to the use of square bodied streetcars (as the horses used to pull those cars before electricity, as well as being commonplace in large urban metropolises. Whether this actually held true, remains to be determined by an animal behaviorist. This author, having lived in rural Upstate New York; and now living in rural Texas; I can say with increasing regularity; I have personally seen people on horseback, on the shoulder of busy town or even county road. Cars approach these horses a hell of a lot faster than these steam locomotives did at 6 miles an hour; and they do not seem to be easily spooked. Irregardless, steam locomotives with their reciprocating pistons and rod movement apparently would spook some horses; so the locomotive was covered in a dummy carbody. This was common on many passenger and freight railroads that operated on the street, and was not specific to operations in New York City. However, the use of steam dummies / dummy engines was more prevalent in urban situations as there was more interaction between the actions and operation of the railroads with horse drawn wagons, as well as horses being used by the solitary person for transportation. |

|

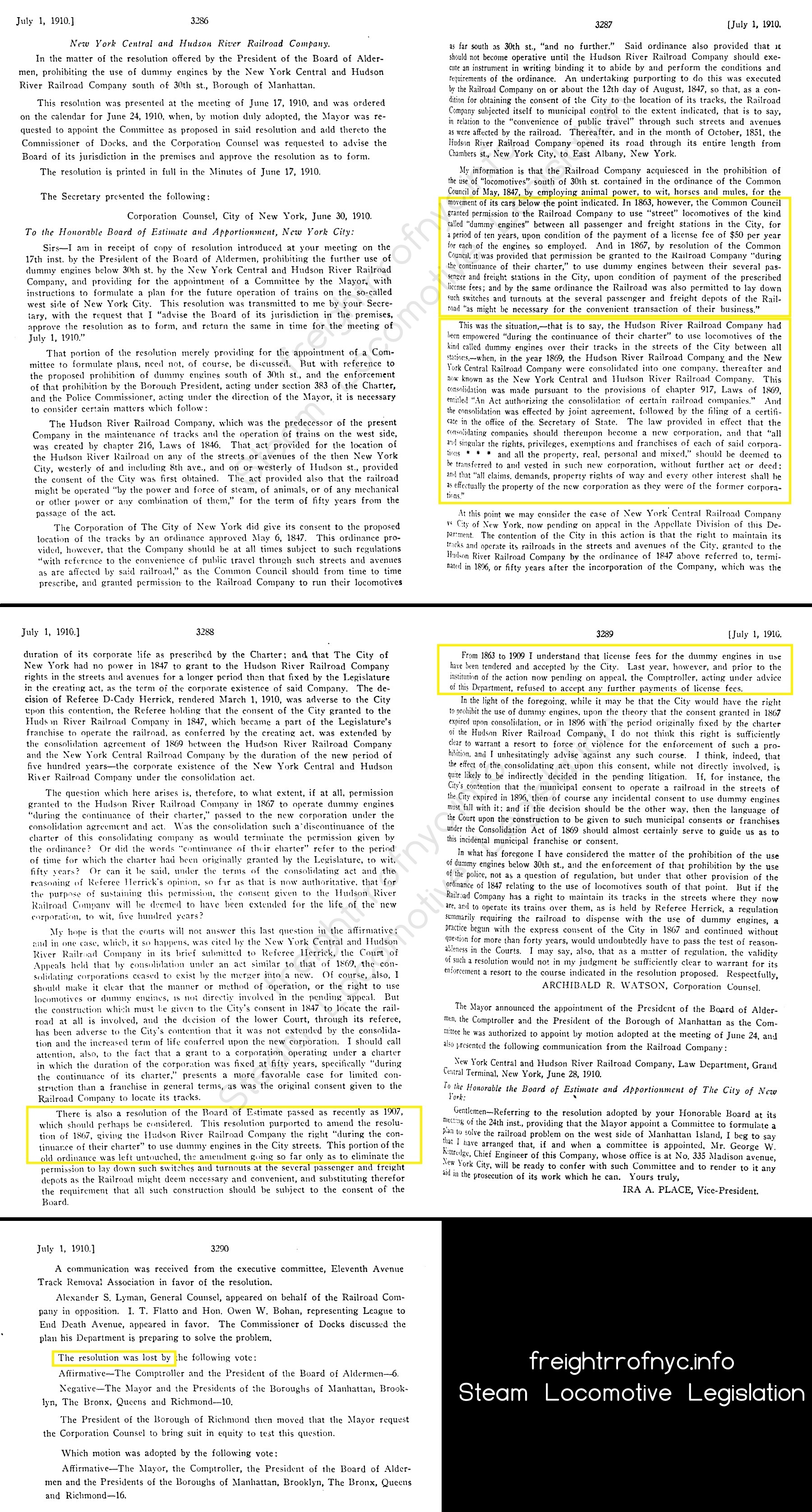

| Another attempt to "evict" the freight operations of the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad. Failed. Even the Corporation Counsel Archibald Watson stated, the railroad was within its rights to operate, as the City had granted them permission to do so. The Mayor and all 5 Borough Presidents agreed. |

.

.| 1923 | June 1 | legislated | to take effect January 1, 1926 | ||

| 1924 | amendment | to expand scope of area | NYS | approved | |

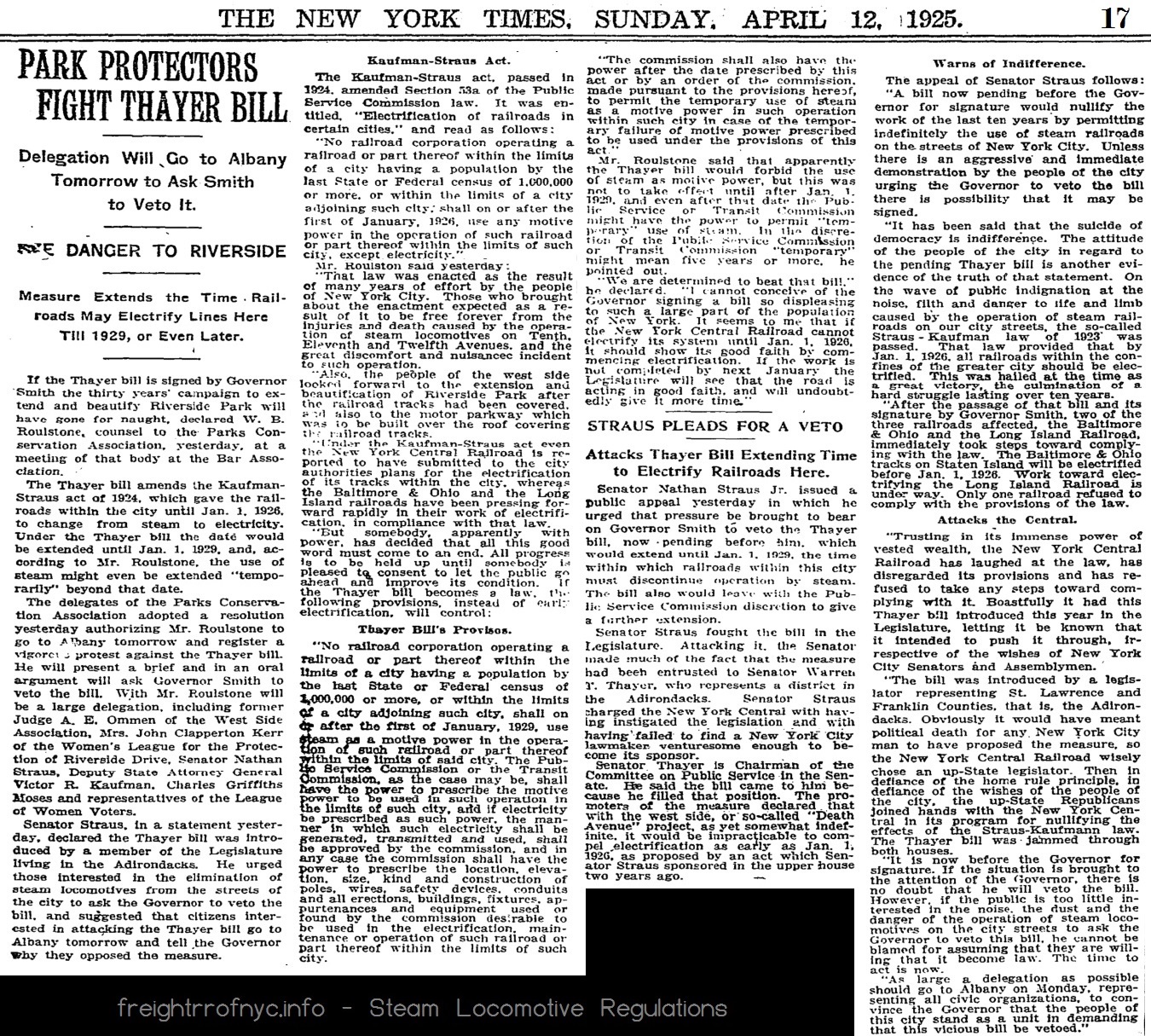

| 1925 | April 13 | amendment - "Thayer Bill" | for 5 year extension | NYS | vetoed |

| 1925 | December 31 | temporary injunction | NYS | approved | |

| 1926 | March 26 | permanent injunction | NYS | decision reserved | |

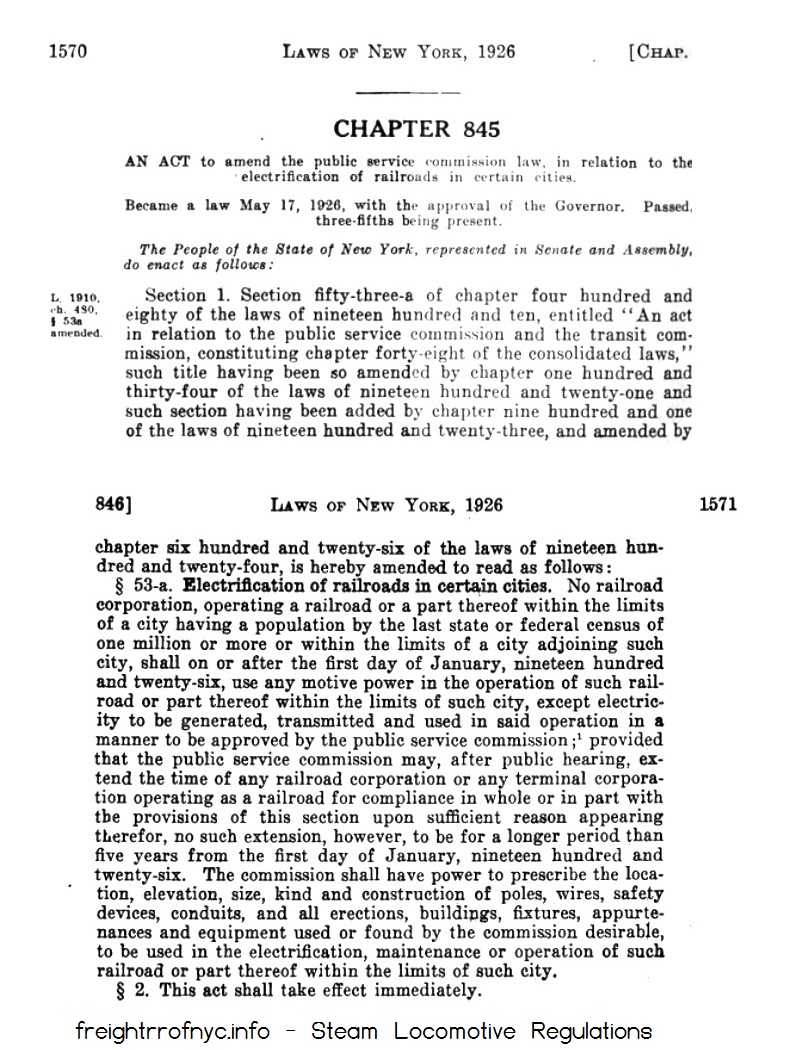

| 1926 | May 18 | amendment | for 5 year extension | NYS | approved |

| 1926 | September 9 | overturned by US Court | unconstitutional | US | approved |

| 1930 | State legislation | NYS | repealed |

| Born

on March 14, 1896, the son of Edward Kaufmann and Sarah Rossman. His

father Edward was County Clerk of Kings County for several years and

chairman of the Municipal Tax Commission. Victor attended DeWitt Clinton High School, Far Rockaway High School, and Cornell Law School, graduating from the latter in 1918. He also graduated from the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, after a special three months course. During World War I, he served as an ensign in the United States Naval Reserve. In 1919, Kaufmann was admitted to the bar. In 1921, Kaufmann was elected to the New York State Assembly (R), representing the 7th District of New York County (Manhattan). While in the Assembly, he sponsored the Kaufman Act in April 1923. He served in the Assembly until 1924 and was also chairman of the Assembly's military affairs committee in 1924. Kaufmann served as Deputy Attorney General of the State of New York from 1925 through 1931. He was a member of the New York State Executive Committee in 1928. He began serving as assistant clerk of the Assembly in 1936. he was also secretary of the Republican New York County Committee when Kenneth F. Simpson was chairman. In the 1942 election, he was chairman of the Dewey Volunteers, a nonpartisan organization that worked to elect Thomas E. Dewey as Governor of State of New York. He passed away on February 5, 1943 while under an operation for an abdominal issue. He was survived by his wife Anna, and a daughter Shirley Ann. |

|

|

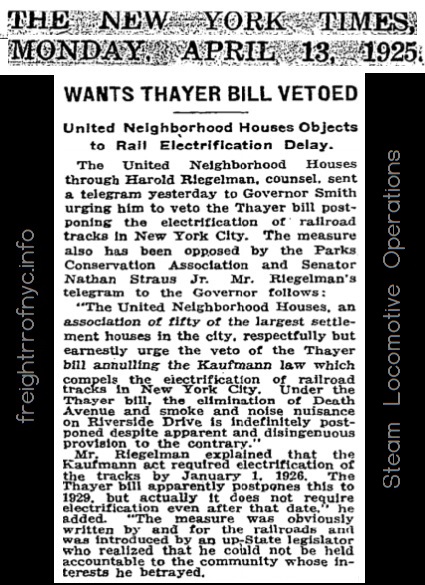

Nathan Straus Jr.

(1889–1961) was a Democratic politician and journalist who served in

the New York State Senate from 1921 to 1926. He was the son of Nathan Straus, a co-owner of Macy's department store and a prominent philanthropist, and Lina (née Gutherz). He attended Princeton University as well as the Heidelberg University. He worked as a reporter of the New York Globe from 1909 through 1910; and was also editor of Puck Magazine from 1913 through 1917. During World War I, he served as an ensign in the United States Navy. after the war, he became Assistant Editor of the New York Globe, but left in 1920 because of that publications support for Republican presidential candidate Warren G. Harding. Instead, Straus entered politics as a Democrat, and was a member of the New York Senate from 1921 through 1926. During his three terms, he introduced legislation of mandatory automobile insurance, female inclusive juries, and ratification of the Child Labor Amendment. Straus chose not to run for reelection in the Senate in 1926. Straus was married to Helen (née Sachs), daughter of Bernard Sachs, a neurologist for whom Tay–Sachs disease is named and member of the Goldman-Sachs family. They had four sons: Nathan Straus III, Barnard Sachs Straus, Irving Lehman Straus, and R. Peter Straus. On September 13, 1961, Straus was found dead in a motel room in Massapequa, New York. According to his family, he suffered from a heart condition, and it was determined that he died of natural causes. He is buried at the Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Hawthorne, New York. |

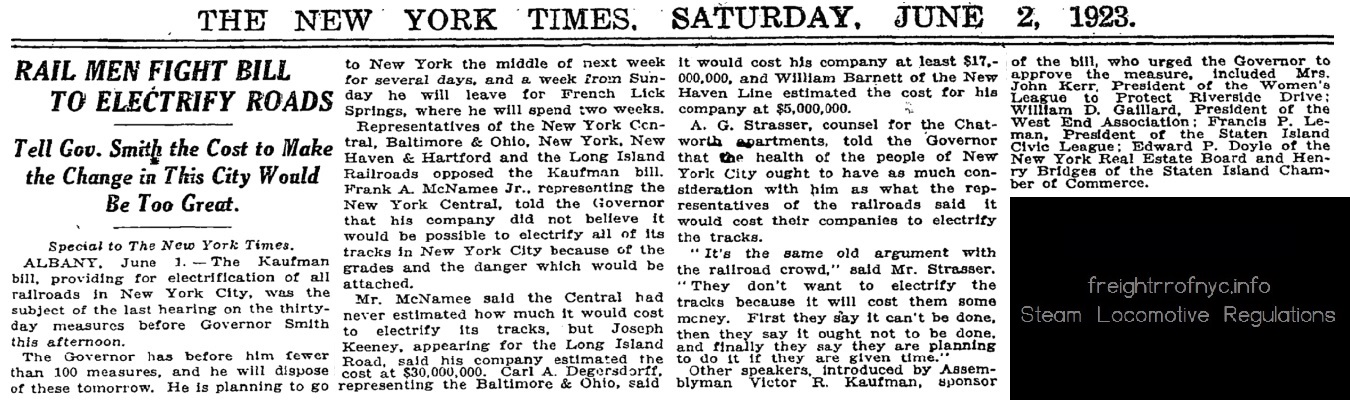

| The first inkling that Kaufmann was up to something appeared in the April 7, 1923 edition of the New York Times. This is very first mention of it I can find in the New York Times. MAY BAR STEAM TRAFFIC

Assembly Committee Reports Bill to

Electrify Riverside Drive Freight Tracks

|

|

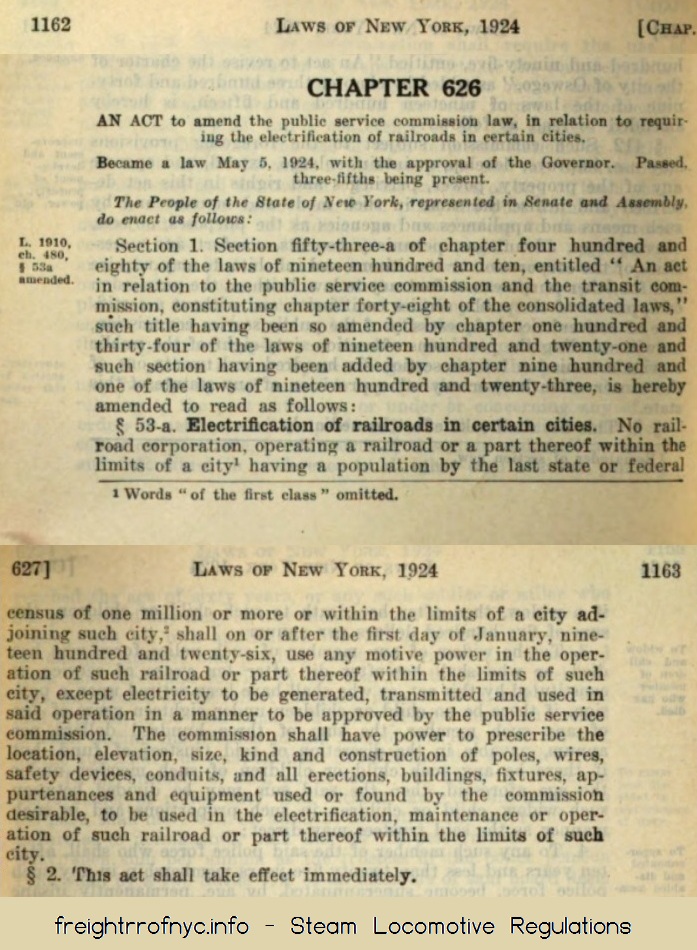

Chapter 901 §53a

Section 1. Chapter four hundred and eighty 480 of the laws on nineteen hundred and ten 1910, entitled "An act in relation to the public service commission and the transit commission, constituting chapter forty-eight 48 of the consolidated laws," such title having been so amended by chapter one hundred and thirty-four 134 of the laws of nineteen hundred and twienty-one 1921, is hereby amended by inserting therein a new section, to be section fifty-three-a 53a, to read as follows:

§53a. Electrification of railroads in certain cities.

"No railroad corporation, operating a railroad or part thereof within the limits of a city of the first class having a population by the last state or federal census of one million or more, shall on or after the first day of January, nineteen hundred and twenty-six 1926, use any motive power in the operation of such railroad or part thereof within the limits of such city, except electricity to be generated, transmitted and used in such operation in a manner to be approved by the Public Service Commission.

The commission shall have power to prescribe the location, elevation, size, kind and construction of poles, wires, safety devices, conduits, and all erections, buildings, fixtures, appurtenances, and equipment used or found by the commission desirable, to be used in th electrification, maintenance or operation of such railroad or part thereof within the limits of said city.

§2. This act shall take effect immediately."

|

Chapter 626 Laws of 1924 at left removes the following words "of the first class" and adds the following: "or within the limits of a city adjoining such city", . . Chapter 845 Laws of 1926 at right, adds the following: "provided that the Public Service Commission may, after a public hearing, extend the time of any railroad corporation or terminal corporation operating as a railroad for compliance in whole or in part with the provisions of this section upon sufficient reason appearing therefor, no such extension, however, to be for a longer period of five years after the first day of January, nineteen hundred and twenty-six.1926 " |

|

|

|

- New York Central

- New York, New Haven & Hartford

- Staten Island Rapid Transit

- Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal

- New York Dock

- Degnon Terminal

Brooklyn Daily Eagle - March 12, 1925

|

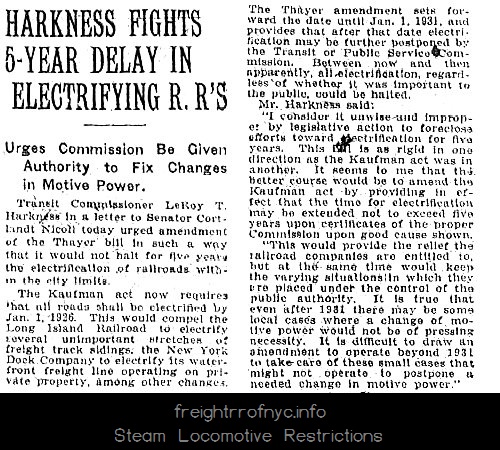

Transit Board Is Against Delaying Electrification Program

Transit Commissioner Le Roy T. Harkness yesterday made public a letter which he had sent to Senator Courtlandt Nicoll, setting forth the position of the Transit Commission on the Thayer bill, which amends the Kaufman act of two years ago, providing for the electrification of all steam railroads in New York City. Electrification under the Kaufman act was to be accomplished by Jan. 1, 1926. The Thayer bill proposes a five-year extension, with further extensions within the power of the Public Service Commission or the Transit Commission to grant. The commission is opposed to the Thayer proposal. "The Kaufman act was aimed primarily at the New York Central west side freight line problem," said Mr. Harkness. "Although general in its terms, it did not take into consideration the varying conditions of railroads in the city, and therefore was too rigid. On this account I have been in favor of amending the Kaufman act, and some weeks ago I referred the matter to the Commission's counsel, General Statesbury, to draft a proper measure. "I have examined the bill introduced by Senator Thayer, and am unable to recommend its approval. I consider it unwise and improper by legislative action to foreclose efforts toward electrification for five years. This bill is as rigid in one direction as the Kaufman act was in another. It seems to me that the better course would be to amend the Kaufman act by providing in effect that the time for electrification may be extended not to exceed five years upon certificates of the proper commission upon good cause shown." |

|

"under the Thayer bill, the elimination of Death Avenue and smoke and noise nuisance on Riverside Drive..."

"The Upper West Side (UWS) in NYC is an affluent, primarily residential neighborhood known for its cultural and intellectual atmosphere, with residents often commuting to Midtown and Lower Manhattan. It features a high median individual income, an older median age, and a mix of upscale housing, including luxury high-rises, large apartment buildings, and brownstones."

|

| . |

Brooklyn Daily Eagle - December 31, 1925

|

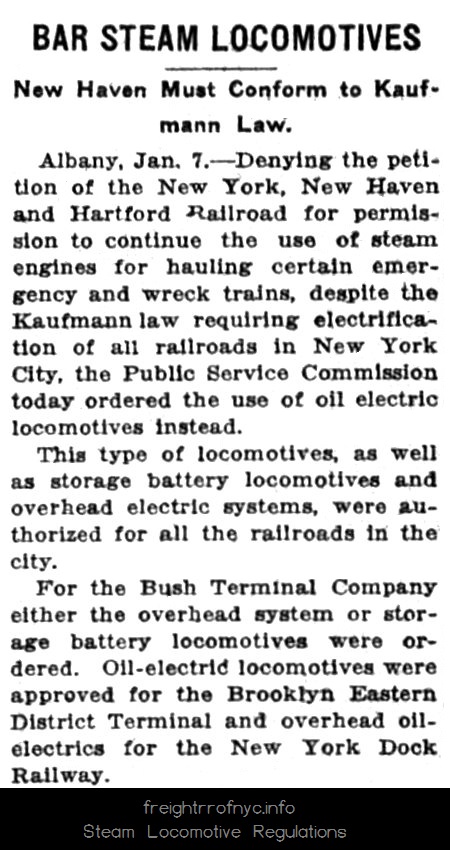

However, before

we celebrate this victory, there is this Brooklyn Daily Eagle article

dated January 7, 1926 (seen at right):

"Denying the petition of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad for permission to continue the use of steam engines for hauling certain emergency and wreck trains, despite the Kaufmann [sic] law requiring electrification of all railroads in New York City, the Public Service Commission today ordered the use of oil electric locomotives instead.What some might not realize, is that Bush Terminal Railroad already had overhead trolley wire powered locomotives in operation on the street trackage that they shared with streetcars on First and Second Avenues in Brooklyn. These electric locomotives augmented the steam locomotives, which were used within the yards, sidings and pier tracks. So Bush Terminal would only have to electrify the unpowered areas, the sidings and the Bush Terminal Yard between 51st and 43rd Streets, not their entire operation. Also, it is worth mentioning that the New York Dock Railway also had fielded a single overhead trolley wire electric locomotive back in 1903, which was sold in 1908. Whether the New York Dock Railway still had any overhead trolley wire at the date of the Kaufman fight, remains to be learned. It is most interesting to learn that the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal was "approved" for oil-electric locomotives. |

|

It is also stated, incorrectly; the Central Railroad of New Jersey #1000 was the first diesel-electric locomotive. It was not, in regard to several categories. So much has been written on the development of the diesel-electric locomotive; it would be both foolish and unproductive to condense it and re-iterate it here. If detailed histories of these experimental locomotives, and the success stories; is of interest to you; it is contained in "Dawn of the Diesel Age", by John Kirkland. I highly recommend it. . First Diesel Locomotive in the World In 1906, Rudolf Diesel, Adolf Klose and the steam and diesel engine manufacturer Gebrüder Sulzer founded Diesel-Sulzer-Klose GmbH, to manufacture diesel-powered locomotives. Sulzer had been manufacturing stationary diesel engines since 1898. In 1909, the Prussian State Railways ordered a diesel locomotive from the company.

After several test runs between Winterthur and Romanshorn, Switzerland; this diesel–mechanical locomotive was delivered to Berlin in September 1912. It had a 2-B-2 wheel arrangement (4-4-4 under the Whyte steam notation system), and weighed 207,000 pounds. The two cycle, four cylinder engine, had a 15½ " bore by 21½" stroke "Vee" engine (cylinders mounted at 45 degrees) and developed 1,200 horsepower, powered the center four driving wheels through a jackshaft drive system, and reached a sustained speed of 62½ mph. The starting system of this locomotive was somewhat complicated. A smaller diesel engine ran a compressor to get the air pressure reservoirs up to 600 to 1000 psi, and after this was attained; the reservoir air and the compressor air combined was then discharged into the main diesel engine to get the locomotive moving, basically as a compressed air engine. When the locomotive speed reached 6½ mph, the main diesel fired, and the auxiliary diesel shut down. Road testing the locomotive took place in 1913 on the Swiss Federal Railways between Winterthur and Romanshorn; Switzerland revealed testing two significant deficiencies:

Page 65 of "Dawn of the Diesel Age" (Kirkland) states the locomotive was moved to Prussian State Railways in Germany and operated on the Berlin-Mansfield Line in 1914 A Wikipedia reference to a "From Steam to Diesel: Managerial Customs and Organizational Capabilities in the Twentieth-Century American Locomotive Industry" (Churella, Albert J. -1998; Princeton University Press; ISBN 978-0-691-02776-0) stated that the issues were unresolved and further trails were prevented due to the outbreak of World War I. Never the less, successful or unsuccessful (depending on your criteria), this locomotive is the first locomotive to use diesel compression ignition engine. In 1924; a diesel-electric locomotive was built by Maschinenfabrik Esslingen (Esslingen Machine Works) with a 1-E-1 wheel arrangement (2-10-2 Whyte) for the Soviet Ministry of Railways. The locomotive went into service on the Moscow-Kursk route; and by 1933; had accumulated 350,000 miles. A diesel mechanical version was built immediately following. Both these locomotives are discussed on pages 83 and 84 of "Dawn of the Diesel Age". . In the United States Closer to home, here in the United States; both General Electric, Ingersoll-Rand had already been experimenting separately with compression ignition powered locomotives for some 8 years prior to the Kaufman Act (1923), as well as Baldwin Locomotive Works and Westinghouse Electric. To be clear, small gasoline powered (spark ignition) mechanical transmission industrial locomotives, and passenger / baggage motor cars built by J. G. Brill, McKeen, EMC (Electro-Motive Corporation) and others; were already plying short-line railroads around the United States. But they were not suitable for heavy switching work. General Electric had been experimenting with gasoline engine - electric drive locomotives, but they too always came up short. . The first Diesel-electric locomotive in the United States

Ironically; the Jay Street Connecting Railroad, located in Brooklyn and the smallest of the offline rail-marine terminals; had already hosted not one, but two different internal combustion - electric locomotive prototypes built by General Electric.

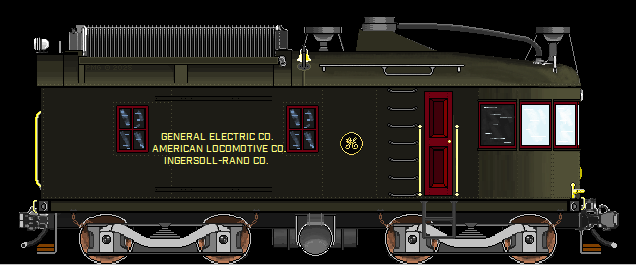

. The first SUCCESSFUL Diesel-electric locomotive in the United States Returning to the specificities of the New York Terminal area, it was the (then) looming compliance date of January 1, 1926 of the Kaufman Act, which really spurred on advances and perfection with the form of diesel-electric propulsion for locomotive power. As a result, Ingersoll-Rand, constructed the following prototype, the GE-IR model X3-1, but it is better known by its construction number: #8835. The locomotive was fitted with an Ingersoll inline six cylinder (10" bore x 12" stroke) diesel engine designed that utilized a block and mechanical design perfected by John Rathbun (a longstanding expert in gas, oil - distillate (similar to kerosene) and heavy oil engines, with solid fuel stream fuel injectors of the Price design (instead of air-blast). Hence the engine being known as a P-R, for Price & Rathbun. This engine developed 300 hp at 550 rpm. This engine in turn, powered a General Electric TDC6-200 electrical generator. The generator in turn furnished electricity to four HM840 traction motors, also manufactured by General Electric; with voltage and current being regulated using controls designed a few years prior by Dr. Hermann Lemp, formerly of General Electric and now working for Ingersoll Rand. The carbody was a left over, laying around at General Electric's Erie, PA facility. This carbody was unique in that one end, the front, was a rounded or bullet nose as was the roof; but the rear end was squared. Nevertheless, both ends contained a control stand for bi-directional operation.All told, this locomotive tipped the scales at 120,000 pounds or 60 tons. The first start up of this locomotive occurred on December 17, 1923. It was not exhibited for public demonstration until February 28, 1924, at the Phillipsburg, NJ plant of Ingersoll-Rand. Initial starting of the Ingersoll engine, if the on-board air supply was depleted, was accomplished with a Mianus gasoline powered air compressor. However, with the Ingersoll engine running, it drove a primary air compressor to maintain the 200 psi necessary for on-board storage and starting, if necessary. The other important factor about this locomotive, was that it utilized engine and electrical components that were already in production, i.e.: were readily available from parts sources. The engine, had already been in production for several years by Ingersoll Rand; and the engine unit required few and minor modifications to adapt it to locomotive use. The fuel injector mechanism was also produced by I-R; so parts were readily available and easily repaired if need be. The generator and traction motors were available on dozens if not hundreds of previous models of General Electric all-electric or gasoline-electric locomotives or motor cars. Unlike all locomotive designs prior to it; the Ingersoll-Rand design, with its B-B wheel arrangement, a rigid truck wheelbase of only 7' 2" and a 35 foot overall length; was a much more logical choice for the tight curve radius (in some cases 90' foot radius or less) as well as the repeated stop and go and idling as typical of the yard and switching operations of the various offline terminals located in and around New York City.

Sam Berliner III (RIP), had authored an extremely knowledgeable (and enjoyable) website containing an in-depth history on the development of the oil-electric locomotive, including the resulting commercial models sold. His website contained images, rosters, and specifications thereof in great detail, however upon his passing; the website was removed from the web. I did manage to download most of the pages before it was removed.

Sam also related to me when I first entered this research many years ago, and had this to add and it should be noted:

. #8835 would be "unveiled" on February 28, 1924; to representatives of the following railroads of whom were showing interest in a diesel-electric switching locomotive. These were the Baltimore & Ohio, Pennsylvania, Boston & Maine, New York Central, Reading and the Lehigh Valley Railroads. While their men were impressed, they remained unconvinced of the design which had not seen day to day service yet. So, beginning in June 1924, and for the next thirteen months; #8835 went through rigorous (and to some extent, abusive) testing on ten different railroads and three industries (to which the locomotive had been leased on a trial basis). Ironically, #8835 would come to spend quite a bit of time operating on the West Side of Manhattan along Tenth and Eleventh Avenues for the New York Central Railroad: . According to Diesel Spotters Guide, by Jerry Pinkepank, Kalmbach Publishing; the locomotive was broken in at the Ingersoll-Rand plant at Phillipsburg, NJ. The breakdown of hours of service per railroad are as follows.

Three

notable accomplishments took place during this trial phase: 2

It also "partook" of a tug of war with a

60 ton 2 truck Shay type locomotive of New York Central and in use on

the West Side of Manhattan; in which the #8835 won that battle

due to smoother torque of the electric 3

Midpoint through its so-far successful testing, (in which it operated

for seven months in almost continuous use), the locomotive was returned

to Ingersoll-Rand. The engine was disassembled for examination and

Without any room for doubt, it was clear that the prototype design of this locomotive proved to be durable, efficient, reliable, easy to maintain and easy to operate. However, #8835 was never intended to be sold; and after demonstration, it went back to General Electric shops. Note in the diagrams above, there is no bulkhead between the engineer and the engine. It is known that production "consortium" model B3-1 locomotives would have a bulkhead (cab wall) for sound attenuation in consideration of the engineers hearing. This is not to say that the Baldwin Locomotive Works was ignoring this developing situation either. They too developed a diesel-electric locomotive, the #58501 in June 1925; with two Knudsen "inverted V6" engines which generated 1000 horsepower with the crankshafts of the two engines joined in a gear drive to a single generator shaft. Although the design was stated for road and yard service, the locomotive was of C-C wheel arrangement, with a rigid truck wheelbase of 12' 8" and its overall length at a stated 52 feet 1¾" and a which was more conducive of wider radius curves, road service or large relatively straight ladder yards, as opposed to the small condensed yards with sharp curves as encountered in the City of New York terminals. While this locomotive handled 1000 ton trains on .7 grade at 16 mph during testing the locomotive did not meet expectations.

.

In turn, the storied success of this locomotive, led General Electric and Ingersoll Rand to build and market a "big brother" to this locomotive: a 600 horsepower (two 300 hp engines) 100 ton boxcab for heavy switching and road service, which became available in December 1925, and of which many railroads purchased, including the Long Island Rail Road and Erie. Both of these models were widely received by the Class 1 railroads as road switchers as well as by heavy industrial operations such as the lumber and steel mills.

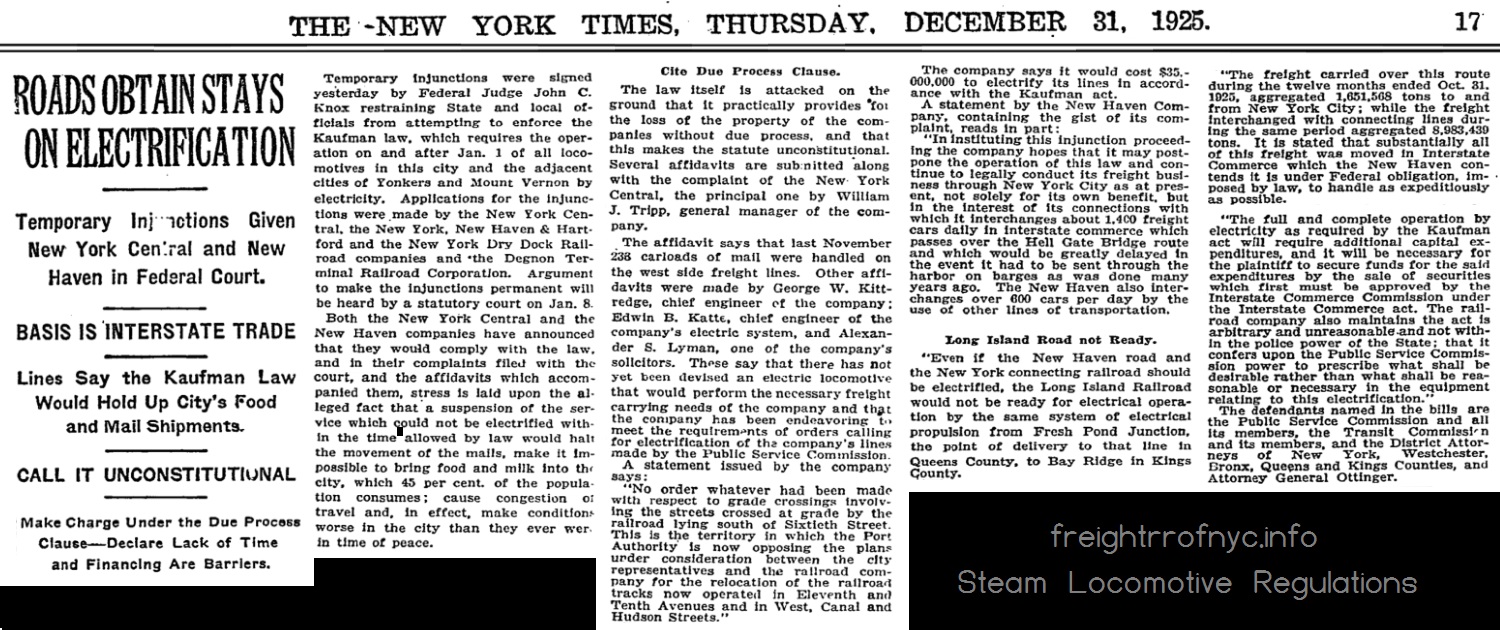

With a successful injunction in their pockets, allowing them to hold off the demanded changes as stipulated by the Kaufman legislation by 1926; the railroads continued the legal battle to invalidate the Kaufman Act. I'm no attorney, but I take particular note of the statements by Robert S. Bayer, Deputy Attorney General; "He also pointed out that any fines imposed could be so low as to have no effect whatsoever upon the finances of the company." If that is such the case, why ratify a bill with a $5,000 per day fine? Why not $500? No doubt the act was to gain the attention of the railroads, but perhaps it went too far in its scope? I also take note of the statement by Mr. Lyman representing the New York Central; "In discussing the electrification of the lines of the company on the west side he said that street crossings from Spuyten Duyvil to St. John's Park would have to be eliminated."

Ultimately, decision was reserved; meaning it was put off until a later date. Now, we are beginning to see procrastination on the part of the courts. Why? .The State of New York Capitulates

(Charlie Halloran) [sarcasm] "Tell them the New York State Supreme Court rules there's no Santa Claus. It's all over the papers. The kids don't hang up their stockings. Now, what happens to all the toys... that are supposed to be in those stockings? Nobody buys them. The toy manufacturers are going to like that. So they have to lay off a lot of their employees... union employees. Now you got the C.I.O. and the A.F.L. against you. And they're gonna adore you for it. And they're gonna say it with votes. Needless to say, a man can strip his gears changing opinions like that. If it means anything coming from me; if the decision was legitimately based on Governor Smith's actual opinion having changed based on the information he had in his hands (and not from someones bag of campaign contributions being held over his head while his other arm is being twisted behind his back) than I owe Governor Smith a great deal of respect.

. September 9, 1926 was a red letter day for the railroad in the New York City area.

In simplest terms, the Kaufman Act interfered with interstate freight operations. That made it a Federal matter. In all, it was relatively a quick legal fight, three years from when Kaufman introduced the legislation in 1923 to 1926 when it deemed unconstitutional. But a lot took place in those three years.  Brooklyn Daily Eagle - September 10, 1926 .

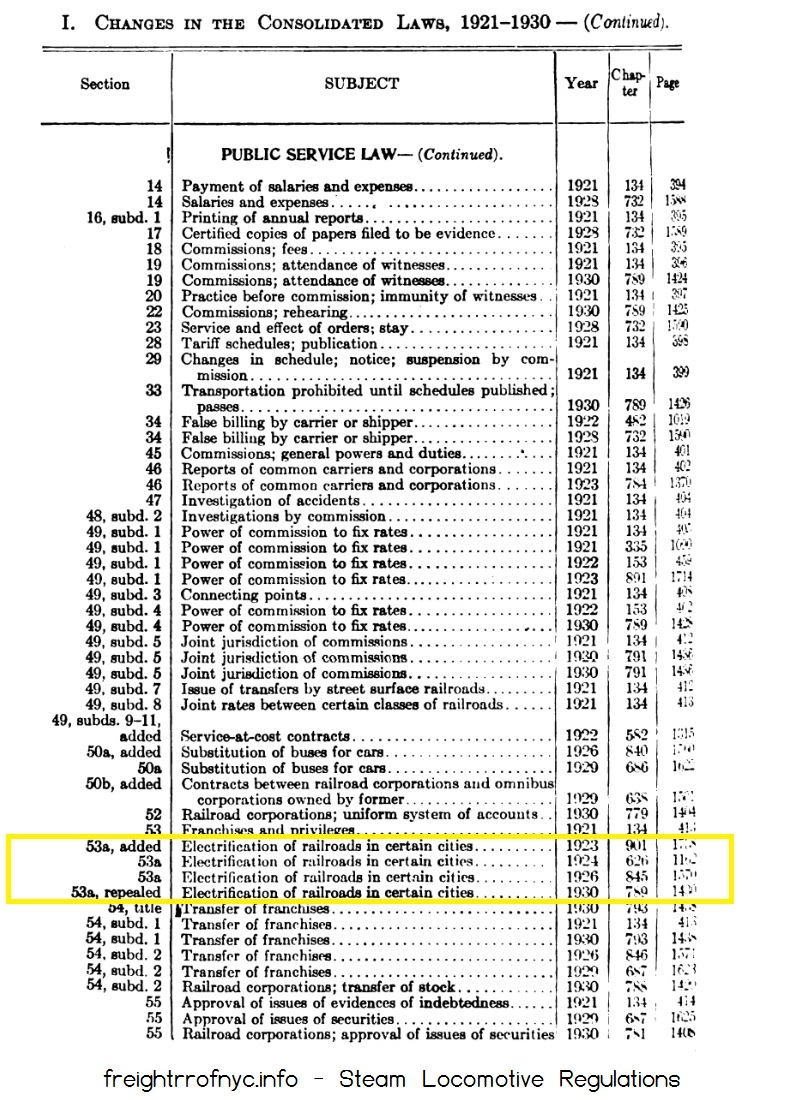

. This

table shows all the changes in the Consolidated Laws, 1921-1930, at which they reflect

there were only four hearings held reflecting upon the Kaufman

Electrification Act.

. At this point my research reaches a dead end... I can find no other references or legislation, proposed or enacted in response to the invalidation of the Kaufman Act. If there are any, please bring it to my attention immediately. I provide this document above to show there were no further amendments to the Kaufman Act. Now it has been stated repeatedly in various venues, discussions and forums; that there was an amendment of the Kaufman Act in which it was re-written to include diesel-electric locomotives as an option to replace steam locomotives. I can find no evidence of this amendment, and the list of amendments as shown above, and shown on this page do not reflect such wording. There were four filings / amendment regarding the Kaufman Electrification Act: ratification of the the initial Act, amendment (area expansion), amendment (five year extension), and the repeal. All are duly shown on this website, as recorded above. There was no amendment to the Act, that mentions "diesel-electric locomotives." Yes, history clearly shows the obvious success of the diesel-electric locomotive now allowed a second "power" option for the railroads to use in order to comply with the law, and obviously of which some railroads took this route, but the clearly stated reason of the invalidation of the Kaufman Act was its unconstitutionality based on federal powers having authority, not state; and no mention of the diesel-electric power is mentioned.

Nowhere does it say, an alternative or less polluting method of propulsion had been developed to replace steam power. Further reinforcing this finding, is I can find no other City or State filings or appeals filed in opposition to this decision. I can find no further regulations or legislation filed by Kaufmann (he filed four bills through his tenure, the other three have no relation to transportation.) So let us recap: With this being the case for the time being, the railroads were free from complying with the Kaufman Act. Here is a time line showing date of various legislations as opposed to the railroad demonstrator testing and taking possession of production model locomotives. You will note some of the railroads took delivery of their locomotives after the temporary injunction was granted and even after the Kaufman Act was found unconstitutional. . Time Line of Events related to Kaufman - Straus Electrification Act

While the stated object of the Kaufman Electrification Law was to remove steam locomotive power from the streets of New York City, it could be considered successful in reaching this goal. It spurred on the advancement and perfection of a suitable replacement; the diesel-electric switching locomotive design. However, as a circuitous way to get the New York Central Railroad off the streets of New York, it failed. It would take several more years of negotiating to make that goal a reality. And after Kaufmann's bill, he moved on to better things in politics, so it was up to others to make that goal a reality. Technically speaking, a law can be found unconstitutional by a court, but still remain on the books in an unenforceable state, like the Kaufman Act would do until 1930, when it was officially repealed by the New York State Legislature. Unconstitutional laws usually are accompanied by an editors note and citation to the finding of unconstitutionality. But, the fact still remains, the Kaufman Act was found unconstitutional, but the State of New York did not repeal it until in 1930. Therefore, there is no longer a legislation in the books prohibiting steam locomotive operations in the City of New York As Papa Boule says, "Fire up that engine!" If my estimation is correct, this belief that "steam locomotives are banned in the City of New York"; is as erroneous as the so called "ban on camelback locomotives", whereas this so called ban has been exhaustively disproven by Gregory P. Ames.

. . I can hear the rail enthusiast asking now, "If the railroads were victorious and successful in overturning the Kaufman Act, why did most of the railroads still switch to diesel-electric locomotives?" There are multiple reasons, and I will address them: 1) Cost Effectiveness in both Operation and Maintenance

The first is a very logical but mundane fact: the same reason diesel locomotives replaced steam locomotives in the City of New York, is why railroads gave up steam locomotives in other parts of the United States as well. The railroads realized that the diesel-electric locomotive was more economical to operate. This may be a difficult thing for the "rabid railfan" to digest, as well as we are now living in a society where we are pretty much find someone else to blame; but the phase out of steam locomotives was not because it was "banned" by the Victor Kaufmann, or the Kaufman Act, but the steam locomotive was in fact an expensive and time consuming piece of equipment to maintain. . Cost of Operation: The Central Railroad of New Jersey conducted a cost analysis between #1000 (A/GE/IR 300 hp 60 ton diesel-electric boxcab locomotive) and #840 (the 0-4-0T steam locomotive) The first 100 days of operation of #1000, cost the Central Railroad of New Jersey $301.By comparison, the last 100 days of use of #840, in the same function at the same facility in the Bronx, operation of this locomotive cost the Central Railroad of New Jersey $1420. For the record, #840 was in good shape, and would go on to yard switching duties at Jersey City. It was still in operation in February 1952, but would be scrapped in 1954. So, when replaced,in the Bronx, it was stil a viable piece of equipment, not some "hunk o' junk" on its last legs. Diesel-electric locomotives saved the CRRNJ over $1,100 in 100 days. And this was a single locomotive, at a single facility. When you extrapolate that to an operation on the scale of the New York Central's West Side Operation, with no less than a minimum of five locomotives operating simultaneously (and frequently more in the area of a dozen locomotives operating), the cost savings realized is enormous. This is exemplified by the table in the General Electric catalog. Daily and Long Term Maintenance & Repair The diesel locomotive did not need to be kept under steam if not being used, as a steam locomotive did. If it was done being used, a diesel locomotive could be "shut off." Steam locomotives on the other hand, needed a hostler to maintain the fire during off hours of operation; and if not being used, the steam pressure was allowed to drop for the duration. This took time to get the locomotive back up to operational pressure again. After operation, a steam locomotive needed to have the ashes needed to be dumped out of the ash pan. This required going back to the engine house or ash pit, as you couldn't just dump your ashes in the middle of the street. This required time. Time cost money. Diesel locomotives had no such burden. Furthermore, steam locomotive boilers had to be inspected every 30 days. This required "dropping the fire" (allowing a steam locomotive to go cold). This was not beneficial to their longevity. Excessive heating and contracting of the firebox and boiler between cold and hot cycles fatigued the metal, therefore keeping a steam locomotive "hot" increased reliability and reduced down time. While small locomotives gained steam pressure quicker than larger counterparts, it still took time. But even these 30 day inspections still impacted on the work cycle of a steam locomotive. If a defect or breakage was discovered, the locomotive would have to be sent where the men that specialized in various fields, i.e; boiler

repair;

wheel balancing, truing & turning; cylinder packing, or any other

of the special equipment needed for such repairs were located. In contrast, a general mechanic could repair the diesel-electric locomotive, usually on location; without the need for sending the locomotive back to a large repair shop. . Safety Furthermore, the inherent safety factor of not requiring a boiler under pressure, is just another case for the diesel locomotive. A steam boiler is essentially a bomb with a safety valve. If the safety valve fails, or the hostler or engineer inadvertently let the water level drop uncovering the fire box? Mucho no bueno. If a diesel locomotive overheats or fails? It just rattled, wheezed, smoked and stopped; with no harmful or fatal effect to workers around it. . 2) Ease of Operation

Operating a diesel electric locomotive is inherently simpler to operate than even a small steam locomotive. In a diesel locomotive, one man can control everything. In regards to the coal fired steam switching locomotives operated by the New York Central (and most other railroads) that were located in Manhattan, the various 0-4-0T and 0-6-0T as well as the Lima Shay's (all were coal fired) therefore they required an engineer and a fireman. . 3) They Already Invested In the Technology

Secondly, the time and financial investment in developing the diesel-electric had already been expended. The railroads approached the locomotive builders to come up with a solution, and these companies did just that, and the railroads placed orders for the purchase of these locomotives in 1926. For the railroad to revert back to steam operation, is equivalent to taking a giant step backward. Yes, we rail enthusiasts all love steam locomotives and they are romanticized and nostalgic, but the steam locomotive is costly to operate. Again, what most rail enthusiasts do not comprehend, is that the railroads are in business to make money, and in the process of making that money also involves the saving money. "A penny saved is a penny earned." If the railroad could save 10 cents an hour in the cost differential between operating and maintaining a steam locomotive as opposed to diesel-electric locomotive, that savings averaged out over years and across a fleet of locomotives, and applied to various locations where the locomotives were use, that 10 cents added up exponentially. This was exemplified by the use of anthracite culm (waste) as a fuel instead of sized anthracite by the Eastern railroads. Culm was cheaper by the ton than its equivalent in screened and sized coal. The initial cost (in both time and effort) in developing a firebox in which to burn it efficiently, was secondary to the cost savings that would come later. This logic can be viewed time and time again throughout railroad history, i.e.: the switch from wood fired locomotives to coal fired. Then, where plentiful and readily available, came the progression to oil fired steam locomotives. Saturated steam gave way to superheated steam. Better valve designs made for better steaming efficiency. As locomotives became heavier, wheel arrangements grew larger, locomotive weights went up and so did the tractive effort. Trains became longer. The resulted in the evolution of rail and rolling stock, 36 foot cars of wood body and steel underframe, gave way to 40 foot cars entirely made of steel. Rail weights increased from 75 pound per yard to 90 pounds per yard then 115 pounds, and eventually all the way up to 156 pound rail. As metallurgy, rolling and hardening methods improved, saw a decrease in the standard rail weights to 115 and 132 pound. In the diesel-electric locomotive era, this can be seen as well, where four or five, or even six, 1500 horsepower diesel-electric locomotives gave way to three or four 2000 horsepower units. These in turn were replaced by two or three 3000 horsepower locomotives. Now two 4000 to 4400 horsepower locomotives are the norm for normal train operations. Technological advances even proved that 6000 horsepower diesel locomotives were possible, but uneconomical. Freight train crews started at around five personnel: conductor, engineer, fireman, and usually two brakeman. With automatic telemetry "end of train devices" or EOT's; a caboose was no longer needed (eliminating the expense of maintaining that piece of rolling stock) and the elimination of at least one of the brakeman. These days, a 10,000 foot train operates with two locomotives and a conductor and engineer. (We will not discuss the ramifications of the proposed one man train crew.) Modern diesel locomotives have autostart technology, that when environmental conditions are favorable, they shut down the engine to save fuel, and reduce emissions. When brake reservoir pressure for holding the train in place begins falling off, or the ambient temperature is dropping, the engine automatically starts to run the air compressor and/or keep the engine block from freezing. . 4) Hedging of Bets

There is also the possibility however remote; that if New York State or any other city, state or federal agency for that matter; attempted to curtail steam locomotive use; the diesel-locomotive was now held as an acceptable alternative in addition to electric. Precedent had been set. This turned out be unnecessary, but who knew at that time - history might have turned out differently. . 5) Being a Good Neighbor

Considering the fact that steam locomotives do in fact pollute the air "more visually" than a diesel-electric locomotive; using a diesel-electric locomotive led to better relations with the public, especially so for those operating railroads in close proximity to residential neighborhoods. This was the "good will" factor. Three parties are more or less content; the residents no longer complaining to the City or municipality in regards to nuisance claims and having to take legal action, and the railroads are for the most part left free to operate with minimal interference. Todays hot-button topics are trains blocking railroad crossings; horn use late at night or in high rail traffic areas e.g: "quiet zones"; and the transport of hazardous materials through occupied areas. . 6) Ulterior Political Motives to be Considered

While the often stated reason for the Kaufman Act was supposedly

"anti-pollution" (smoke & noise); the initial wording of the act

only specified electric locomotives as an alternative, and specified

electrification of

the part of the line through Riverside Drive area, not the entire City.

Subsequent newspaper articles reflect that the initial reasons the Kaufman Act was filed was because of nuisance complaints by Upper West Siders. Therefore, the act had nothing to do with pollution. And when I encountered the following testimony; it was like an epiphany. I personally cannot help but think Harkness literally let Kaufman's cat out of the bag in his March 1925 testimony: "The Kaufman act was aimed primarily at the New York Central west side freight line problem," said Mr. Harkness. "Although general in its terms, it did not take into consideration the varying conditions of railroads in the city, and therefore was too rigid. On this account I have been in favor of amending the Kaufman act, and some weeks ago I referred the matter to the Commission's counsel, General Statesbury, to draft a proper measure." Again, Kaufman's and Straus' electoral districts and constituents were West Siders. The fight to get the New York Central Railroad to relocate or remove their street operations had been in discussion since 1909. No doubt the residents of the West Side had lost their patience. On April 13, 1925, the "United Neighborhood Houses" sent a telegram to Governor Smith, through their legal counsel; also opposing the Thayer bills' proposal of a delay. Looking this article over closely; we read "under the Thayer bill, the elimination of Death Avenue and smoke and noise nuisance on Riverside Drive..." Riverside Drive was north of the street running freight operations along "Death Avenue" (the sensationalist moniker given to street operations on Tenth and Eleventh Avenues, south of West 60th Street.) Riverside Drive commences at West 72nd Street and proceeded north until West 181st Street in Washington Heights, a distance of 5.4 miles. Its location is somewhat aways from the hotbed of street running freight trains tying up pedestrian and vehicular traffic in Midtown. While there were in fact several railroad crossings at various streets perpendicular to Riverside Drive, there was no switching or yard activity along this section of line; therefore transiting this area were "through trains", and henceforth this section of line was not subject to excessive waits and gridlock like experienced in Midtown; much like the railroad crossings that existed along the line in Westchester County. The crossing and streets remained open; until a train approached, then opened again after it passed within a minute or two. Track speed was 30 miles an hour or better. Trains did not sit blocking the streets while switching and reversing back an forth in Midtown. Furthermore, the railroad right of way in the Riverside Drive area was clearly defined and separate from roads and streets and sidewalks. So, why were a bunch Upper West Siders getting on the band wagon? So, it now clearly appears that NIMBYism was at the core amongst the affluent Upper West Siders and the Kaufman Act. Riverside Drive was then, and is still known for the affluent high rent apartments and condominiums built there. They did not incur an inconvenience from a train blocking a street like it did in Chelsea (Midtown Manhattan). It wasn't about reducing pollution. It was about appeasing wealthy and vociferous residents. Once again, people build or buy next to an industry, a railroad, an airport, a seaport, an interstate highway; and after moving in only to find it a nuisance, and they want it shut down or relocated. Say no more. The railroad was routed through the area in 1846-1850. The Riverside area then was wild, undeveloped land. The Midtown residents that were better off financially, and wanting to escape the congestion of Midtown living, now looked to move further north, to where there were views of the majestic Hudson River.. untamed parklands.. then "Wooo, wooooo! Chugga chugga chugga, clickity clack, clickity clack." "What!?! A train goes through here!?!? Oh no, that won't do, no sir. Not at all. Send the train someplace else, anywhere, just not here! I'm going to write my assemblyman." It should be noted, for the record; the City of New York, the State of New York and the New York Central had been negotiating and dickering over the solutions to the West Side issue for decades. As soon as the Central and the City found a solution, the State came in and said it was no good, they wanted control over the matter and wanted something else. More or less, it resulted in a grand state of confusion which it could not be determined which municipal agency had jurisdiction: "In 1911 (chapter 777 of laws of 1911) the West side Improvement was made the subject of special legislation, and the carrying out of the improvement was left generally for direct action between the City authorities and the railroad company. Under the Mitchel Administration plans for carrying out the West Side Improvement were developed in great detail, but at the last the proposed arrangement failed of approval. In 1917, the special legislation of 1911 was amended to confer certain jurisdiction of the (state) Public Service Commission for First District (chapter 719, laws of 1917). The Central would agree to the States' request; and now the City wanted something else, something more. And for quite some time, the New York Central kept agreeing to finance those growing requests. It went back and forth for months, months turned into years, years into decades. It was like trying to hit a moving target. Surprisingly, according to the recorded negotiations, the Central was repeatedly agreeable to the mounting costs. The residents of the West Side elected a man who vowed to get the New York Central to relocate or cease operations altogether. But let us face it, if Kaufmann went on record with his sights set on only the New York Central (as others had done prior to him), he would get no farther than the others before him. So it is my opinion here, that he disguised his attack on the Central's operation as something much more palatable and sympathetic to a wider audience as well as the courts, that being anti-pollution; and with that he took a "shotgun approach" in that his attack now applied to all the railroads operating in New York City. In todays parlance, we call it "going nuclear". Everybody loves a good "David" (Kaufmann) versus "Goliath" - (the big bad railroads owned by their multi-millionaires) versus the ambitious, young, fledgling politicians striking a blow for the disenfranchised people. Of whom those people living in Riverside were not very disenfranchised - but were spoiled and used to getting their way, whether by paying for it, or screaming louder! It makes for good copy, and makes for easier re-election. But only when successful. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

the issue still remained that freight trains had continued to operate on, and block City avenues and streets on the West Side of Manhattan, from Beach Street all the way to West 60th Street, Tenth, Eleventh and Twelfth Avenues, West Street, Canal Street and Hudson Street.

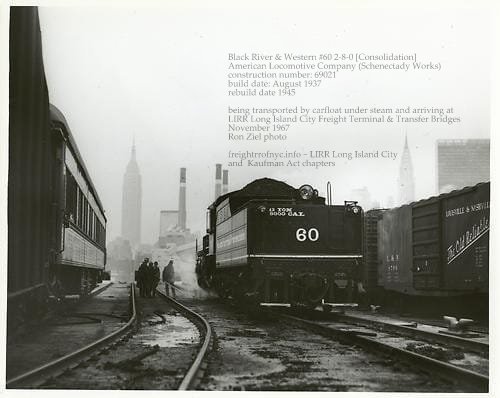

- October 1952 - LIRR #107,

- June 1953 - LIRR #38,

- October 1954 - LIRR #50 and LIRR #111,

- June 1955 - LIRR #39

Like what you see? Suggestions?

Comments?